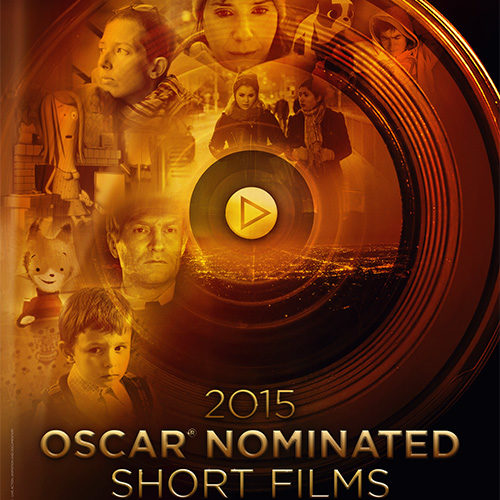

Ahead of the Academy Awards, we’re reviewing each short category. See the Live Action section below and the other shorts sections here.

Aya – France – 39 minutes

It’s nice to take the road less traveled for adventure no matter how wild or tame the unknown journey becomes. That goes for those jumping headfirst and those unwittingly brought along. Because even if you didn’t intend for the unplanned sojourn, you cannot deny its allure once it’s begun. We take stock of the situation, weighing good against bad before ultimately deciding whether the risk is worth any potential gain. For Aya (Sarah Adler), kidnapping a tourist could end in criminal charges if the victim does not understand the adrenaline rush. For Thomas Overby (Ulrich Thomsen), accepting a stranger’s invite of pure, platonic human connection could potentially leave him dead by the side of the road. Looking at their chance encounter objectively, however, only proves just how often we willingly place our trust in those we don’t know.

Written by Mihal Brezis, Oded Binnum, and Tom Shoval (and directed by the former two), Aya is a unique look at two wandering souls letting inhibitions rule to their own surprise. Aya tries to say no to a driver asking her to hold a sign at the airport while he moves his car because she’s waiting for her own traveler to arrive. When given the chance to think, though, something about the mystery of who would come first awakens a gamesmanship relish lost years earlier as a little girl. Life had always brought answers before allowing confusion to overrule order—why would things change now? She’s so certain the person she awaits will exit the plane first to propel her back to normalcy, but fate in this instance brings the wonder of the unfamiliar instead.

There are a lot of unknowns both for the characters and us watching. Will Aya admit to Thomas that she isn’t his driver? Will her doing so leave them at an irrevocable stalemate or find them conducive to the awkward thrill of unexpectedness? And what about the person she was meeting before she turned on a whim to transport someone else’s customer to Jerusalem for no reasons other than excitement? We wonder whether we’d have the guts to do what she does, to take a step out of our lives and see what awaits a fresh slate. It’s not about being wanted, desire, or anything more than a yearning for a reprieve. We take the chance so effortlessly as children yet shy from it completely as adults despite comparable new friendships and connections forever waiting in the wings.

I do unfortunately question the execution of this intriguing idea simply because I wonder if it was fleshed out enough to accept the trajectory these characters follow. It does because there’s no shred of forced romance or salaciousness for the sake of notoriety over authenticity, but also doesn’t considering the blatant manipulations of the story’s structure. I love that we know nothing and are able to watch Aya and Thomas with untainted eyes or interpretations, but the fact I needed to know answers tells me something wasn’t quite perfect. Never did I feel a quietness in my mind to let the actions onscreen unfold in their own time and I admit that’s probably my fault. But while it’s a tad too neat to be a masterpiece, it definitely provides an attractive and memorable venue for curiosity’s checked appetite.

B

Boogaloo and Graham – UK – 14 minutes

There are many examples of fools that Frankie Lymon & The Teenagers could be singing about when their “Why Do Fools Fall In Love” plays during Boogaloo and Graham. It could be Mom (Charlene McKenna) and Dad (Martin McCann) still in love after years together amidst an ongoing military state in Ireland during the 70s. Perhaps the song is about their sons Jamesy (Riley Hamilton) and Malachy (Aaron Lynch) quickly becoming inseparable from the titular pet chickens their father brought home one day from the farm where he works. Or, if a chick does in fact prove to be a hen, it might be the birds themselves desperately attempting to stave off a mother’s desire to see them cooked for dinner by laying an egg.

With love comes compromise and that’s probably the most prevalent message coming across from director Michael Lennox and writer Ronan Blaney‘s film. There’s the compromise Mom makes to allow the kids pets—warm lives breathing in their hands while the world outside home’s constraints is populated by armed soldiers. The compromise the children must confront when big news is announced that entails a necessity to keep the house clean and less crowded than before. And ultimately the compromise of convenience for the type of joy no parent can willingly take away from his/her sons. Through these chickens, Jamesy and Malachy learn the ups and downs of life, the concept of mortality, and an analogy for the changes happening under their roof.

While that sounds overly sentimental—and it is—the filmmakers also find a way to infuse the perfect amount of humor with a crucial moment of danger to boot. The two boys are both more prone to outbursts of emotion courtesy of lewd comments than a sense of humility or acquiescence and they’ll do anything for their birds, even if it means running away during thinto the darkness of night. Just as they do, however, Dad can’t help doing the same for the two souls under his care. What’s a touching depiction of love’s bond and mankind’s inability to remove it for more objectively pragmatic results becomes a time-capsuled metaphor about the lengths we’ll go to keep our own safe. Ireland its people, parents their kids, and children their pets.

B

Butter Lamp – France/China – 15 minutes

The butter lamp is a traditional feature of Tibetan temples and monasteries as a representation of wisdom’s illumination. The light removes the darkness of the mind to focus it and aid meditation. As Buddhists ignite a number of these lamps for funerals and pilgrimages as a way to help the nomads and visitors approach God and the deceased, writer/director Wei Hu utilizes a photographer’s myriad backdrops to allow the world to approach them. These “posters” run the gamut between one of the Dali Lama’s old residences Potala Palace in Lhassa to the entrance of Disney World with every character positioned in greeting. All those unable to leave their village in the Himalayas are now afforded the opportunity to visit with their minds if not their bodies.

Hu presents this process with a single vantage point in Butter Lamp—his photographer’s (Genden Punstok) camera lens. This young man travels from village to village, bringing the Tibetan nomads he meets the manufactured colors of locales they will never see first-hand. Families pose for the portraits, newly weds mime atop a motorcycle with a fictitious home behind, and the mayor’s mother sits as though at the beach once her son’s first pick proves too religiously sacred for her to look away. This is the power of images. Of make-believe becoming a spiritual moment some have been waiting their entire lives to experience. We look at it as a farce because we can go there or mock something up on our computers. But for these villagers this is the closest they’ll ever be to sights from their dreams.

The subjects posing change, their backdrops switch, and the photographer does his best to make everyone comfortable and smiling as though the orchestrator of a fleeting vacation. We listen to conversations as though flies on the wall to their foreign ideas of religion and honor in wardrobe, attitude, and overall appearance. But the most profound reality—and Hu knows it only too well with his final lingering gaze—is that these people reside in a land we can only hope to one day witness. The majesty of Tibet’s mountains is something the neon lights of Hong Kong or feathered costumes of Disney cannot compare. In a way Hu’s photographer’s backdrops become butter lamps for us too, each illuminating a wonder the First World takes for granted in order to comprehend the beauty found in everything.

A-

Parvaneh – Switzerland – 25 minutes

The human condition is on display in Talkhon Hamzavi‘s Parvaneh. Or at least a very optimistic view of what it could and should be whether it takes a little while to get there or not. We like to think there is a universal concept of goodness in us all, but the truth skews closer to selfishness and greed despite the hardships of those we’re willing to take advantage of in pursuit of helping them achieve their own goals. Sometimes, however, our hope for reward puts us in the position to be better—to see how similar we all are underneath the facades society or our own insecurities construct upon our surfaces.

Both the titular Parvaneh (Nissa Kashani) and the young Swiss girl she meets in Zurich (Cheryl Graf‘s Emely) are more than appearances. They are young girls trying to find their place in a world that often feels as though it has no room for them. This is why the former traveled to the Swiss Alps for asylum from Afghanistan and why the latter would rather roam the streets with friends for the next rave than remain at home with a mother who obviously has more important things to do than parent. They are the perfect foils for each other, a conservative girl from another world opening herself up to the city and a rebel seeking something solid in the form of a real relationship beyond quick pleasure.

It’s a touching story that showcases many hot-button issues in subtle ways enhancing the plot rather than screaming for attention. There’s the poor conditions of immigrants, the legal circus necessary to find the sanctuary promised to outsiders, the bureaucratic red tape preventing services from being utilized altruistically, and the horrible misconception of lecherous young men believing any girl out for fun is open for more despite declarations otherwise. It’s a short film portraying how there may be hope in this war-ravaged world if we only start to look at those different around us through a human lens rather than one filtered by entitlement. There is always a common ground if we have the patience and compassion to find it.

B+

The Phone Call – UK – 21 minutes

It’s nice to see an artist who’s unafraid to play with tragedy and find a way to make it transform into a bittersweet glimmer of hope. There’s a fine line in doing so, one that can easily consume the goal into a trite abyss trying too hard to stay afloat within the melodrama. I can see Mat Kirkby and James Lucas‘ The Phone Call proving just as unsuccessful to some as it was touching to me. I wouldn’t say it’s a resounding triumph considering its finale inherently carries with it a grain of salt you must take, but it definitely hit me with enough force to feel some tears welling along with a smile forming for the two characters engaging in a conversation based purely on empathy and compassion despite the futility to do anything else but talk.

It takes a special kind of person to work as a crisis hotline member, especially when you’re not allowed to trace any calls or set up measures to ensure the scared party on the other end of the phone remains safe. It has to be a solitary life—one able to trap you within your own head to confront the darkness you wish you could illuminate but know that watching is all you can do. This is Heather (Sally Hawkins), a shy woman awkwardly greeting a co-worker (Edward Hogg) engaged with his own caller yet never too preoccupied to not wave back with the sort of sheepish desire for affection she shares. While his conversation seems less than life or death, the man (Jim Broadbent) ringing her phone is exactly that.

There’s a beautiful simplicity to what Kirby and Lucas bring to life, one saying much through its performances despite our not seeing more than a single vantage point. They eventually bring us into Stanley’s home, but it isn’t to meet or humanize or pity him. No, we enter his domain to see and hear the clock ticking on his mantle just as one does on Heather’s office wall and the watch she holds. Time is the constant—it’s flux between too much and too little moving back and forth depending on mood, ambition, or defeat. The act of her giving solace is what we latch onto, but his yearning to accept it as nothing more than a friend holding his hand might be even more resonate. We all want to live; few are so certain they don’t.

While Broadbent delivers a stirring portrayal of a man coming to grips with the potentially irreversible deed he’s done in the name of loneliness and love, it’s Hawkins who we watch. She’s phenomenal in the role, traveling from stock checklist queries to genuine concern to heartbreaking helplessness. She tries so hard and with each dead end leaving her caller anonymous never stops being strong when all she wants to do is scream in frustration. You can’t save everyone and if he’s too far-gone she can at least give comfort in his final minutes. To Stan love is worth dying for and even though the darkness such a sentiment carries is painful, there’s something to feeling passionate enough to give you pause about your own life. In the end, it might be Stanley who’s saving Heather.

B+

The Oscar Nominated Shorts are now showing in limited theatrical release. See the official site for more details and our reviews of the other shorts sections here.