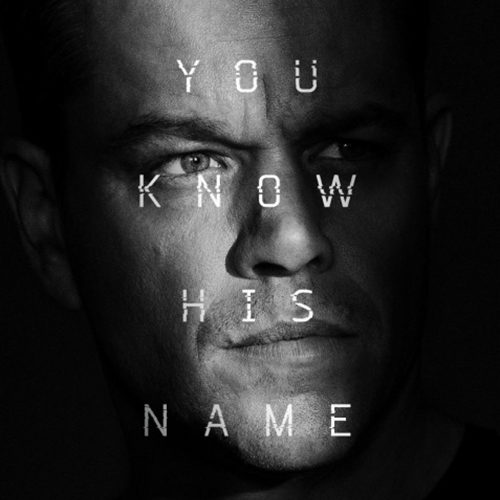

From its beginning, the Bourne series has been defined by a minimalist approach to narrative. Beneath the jargon about multi-tentacled, global terrorist conspiracies and the encroaching dangers of cyber-warfare, it’s fundamentally about the thrills of watching Matt Damon punch things really, really hard. Director Paul Greengrass has been indispensable in bringing across the series’ signature throttling energy and perpetual motion. But Jason Bourne, the fifth installment in the long-running (loose) adaptation of Robert Ludlum’s novels, proves one thing: even the Bourne films can’t succeed with only lived-in camerawork.

Simultaneously pretentious, mind-numbingly tedious, and dizzyingly incoherent from scene to scene, Jason Bourne is the definition of diminishing returns. Greengrass and cinematographer Barry Ackroyd are still nearly unprecedented in their ability to drop into the chaos of action and, more crucially, the ecosystem of conversation. Every scene is still a hurricane as the camera moves with the same force of gravity as its lead. However, coming from a director who’s shown a profound sensitivity for both people and the pronged complexity of the world’s systems, it’s utterly bizarre to see Jason Bourne lifted up on a foundation of craven real-world parallels and a simplistic revenge narrative.

Pummeled into despondency after years of sprinting, hiding, and gunning through the loops of a franchise, Bourne (Matt Damon) is still running away from the crosshairs of his former bosses at the CIA. Jason Bourne picks up with Nicky Parsons (Julia Stiles), who’s still trying to reveal the extent of the government’s misdeeds by sneaking into CIA mainframes. A far cry from the helplessness of The Bourne Ultimatum, this incarnation of the character is unafraid of what consequences her actions might bring, but she’s little more than an early example of fridging, and the tease for a story about the nature of Bourne’s father (Gregg Henry). The so-called revelations are little more than morsels in what is continually built up to be a feast.

All the while, Bourne is being tracked by Robert Dewey (Tommy Lee Jones), the series’ latest in the casting of respected thespians as big bads. He’s not so much a villain as a resolutely old-fashioned man when it comes to security. His descendants have embraced and negotiated their own views on the relationship between individuals and their privacy, but Dewey is the bogeyman because he believes that any level of secrecy prevents him from protecting the country to its full extent. Mostly stuck behind a desk delivering his drowsy drawl, it’s fair to say that Jones’ emergent charisma and abilities for comedy are completely underused. When he almost makes a joke halfway through, it’s an oasis in this criminally serious story.

Dewey is supported by new series additions, Vincent Cassel (known simply as asset) bringing his vacuous sneer as a mechanical killing machine who wants revenge on Bourne, and Heather Lee (Alicia Vikander), a CIA analyst who’s wary of Dewey’s overly murder-y methods. Neither are very memorable, and, more egregiously, Lee is being set up as a continuing character if this series isn’t put out of its misery.

In between, there’s also, inexplicably, a turgid subplot about a tech billionaire, Aaron Kaloor (The Night Of’s Riz Ahmed in a thankless role), who’s made a devil’s deal with Dewey in the creation of his new platform — which will, of course, allow unprecedented access to people’s secrets. Beneath the hilariously reductive techno trappings — I really hope our most “secure” institutions do a better job hiding their work than labeling it under folders that say things like “Black Operations” — Jason Bourne boils down to a less defined version of The Revenant between Bourne and Cassel. Say what you will about the emotional bluster and ostentatious posturing of Alejandro G. Iñárritu’s revenge saga; at least it had the benefit of some undergirding character development.

Jason Bourne is edited (and, for the first time, co-written) by Greengrass regular Christopher Rouse, and it would be disingenuous to say it fails on a script level, as that would suggest that the script existed beyond a bare-bones framework for two hours of jet-setting, stakes-free drama, and the occasional fists of fury. Rouse knows the rhythms of Greengrass’ films backwards and forwards, but those vibes are in service of nothing larger.

That means there’s also never been a more predictive storytelling quality to the editing as it races to the next area in anticipation of a new beat. It further aggravates the feeling that this is a film with no sense of narrative drive other than pure motion. On a technical level, that’s intriguing to think about in terms of how it points to larger messages about our world’s constant vulnerabilities, but that feels more like an accidental conclusion than an organic purpose.

At times, Jason Bourne feels like an attempt to channel the essentialist filmmaking of The Driver, substituting the purity of its sheer inertia for a traditional three-act structure. Yet it still suffocates under incredibly boring exposition about Bourne’s past when it’s not moving. In the moments of action, car and foot chases wind around their environment with complete disregard for spatial geography and a thrilling emphasis on pieces as opposed to the whole, but it’s all sizzle.

For a short period, Jason Bourne even has the illusion of making its narrative’s convolutions a reflection of the tangled, thorny complexities within our modern systems. Like last year’s polarizing but deeply specific Blackhat, much of Bourne is predicated on the understanding of our world networks’ permeability. It’s telling that for a film that spends more than half of its running time on (already) unconvincing imagery of people sparring their way into networks, its visual imagination for these is little more than an arrangement of icons on long monitors.

Jason Bourne scatters philosophies, ideologies, and iconography of the modern world throughout its script. Over and over, there are conversations about what can be done with privileged/unprivileged Internet, and how the world can be improved with the control of technology. Like the film’s main villain, Jason Bourne, has no interest in information or its possibilities. It’s purely transactional — another installment in a franchise that long ago stopped caring about any semblance of meaning.

Jason Bourne opens in wide release on July 29.