What James Franco tries, valiantly, is the equivalent of attempting to novelize Ingmar Bergman’s Persona or Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless. The former is nigh impossible, but the multi-hyphenate took a shot at an equally difficult translation of mediums, adapting William Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying into a movie. Persona and As I Lay Dying are so firmly rooted in their specific medium that trying to divorce the story from the setting would ruin the entire aesthetic experience either work is capable of providing. Breathless, by contrast, has a functional narrative and could be seen as just a pulpy gangster send-up, but doing so largely misses the work’s genius — in a certain sense making a perfect comparison for Cormac McCarthy’s Child of God, a book which, as it so happens, is Franco’s latest endeavor. The medium-specificity of each of these four works can be simplified to one thing: syntax.

To Franco’s credit, he realizes this, but the man’s also an American Literature Ph.D candidate with a passion for film — so the attempt will be made. It’s easy-enough to call the attempt at a translation of the McCarthy text yet another experiment akin to Interior. Leather Bar or As I Lay Dying, but that would instantly preclude one from the many pleasures and intrigues this film has to offer. If you can’t replicate syntax — and, no matter the many wondrous things cinema may provide, you can’t — the best course is finding the essence of the story, putting a twist on it to make this iteration its own interesting work, and honing a unique style and tone that will further allow the adaptation to be effective on its own terms.

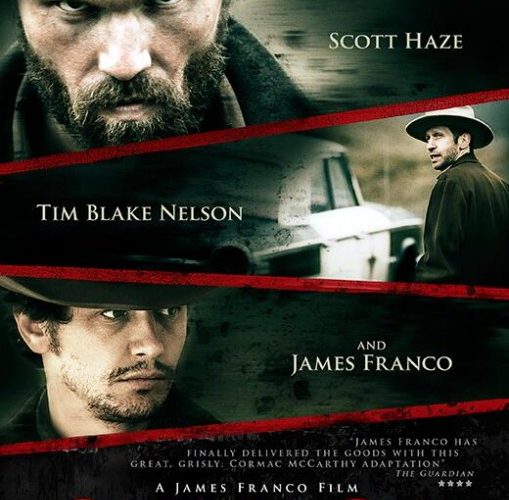

In both regards, Child of God toes the line between success and failure — but, ultimately, leans into success, and occasionally threatens to leap into it entirely. McCarthy’s novel doesn’t go down easy, and while a large part of that comes from his laconic prose, much of it also has to do with the fact that it’s the story of a loose-cannon / psychotic man named Lester Ballard (Scott Haze) who, too, is a necrophiliac. Or, perhaps, it’s more accurate to say that he’s a man who, through a series of (mostly untold) events, has been pushed to the fringes of society, to the point where his only hope of establishing connections is through intimate contact with a dead body — which is to say he doesn’t “happen to be” a necrophiliac so much as he is, in a figurative sense, condemned to and forced into necrophilia.

The idea of someone being “forced” into necrophilia is purposely too much, although treating it as such is Child of God’s first major flaw. Child of God, the novel, works in part because McCarthy’s fascinations with links between isolation, violence, and the nature of mankind are apparent in everything he does; McCarthy makes Lester unquestionably psychotic, and a degree of authorial intent lets us see it as another chapter in McCarthy’s exploration of violence and mankind’s wickedness. Child of God, the film, plays Lester the same way, but Franco’s decision to emphasize Lester’s relationships with stuffed animals — as well as the effect of seeing Lester’s desperation extend to his playing-out a scenario in which a woman invites him inside, eventually to have sex with her — makes the theme of connection more apparent than that of sickness.

Much of this can be attributed to Haze’s impressive, off-the-wire performance, which doesn’t take place around any actors for a large percentage of the film. At the same time, Haze’s speech patterns play up Lester’s craziness more than his loneliness, and many moments that could be devastating are, instead, darkly comic. The more difficult and disturbing themes still make their way through, but in a film that doesn’t shy away from displaying necrophilia and a man’s fecal matter, it pulls one punch too many; Franco fully maintains the grit and seriousness of McCarthy’s novel, but, again, in a novel built so much upon the quality of the written word, an adaptation needs to do more than just translate themes.

Franco lifts the novel’s structure to accentuate Lester’s (literal and figurative) distancing from society, and he also employs a large number of fades to black, often returning to longer and wider shots that give his film an episodic feel. These two strategies imbue proceedings with a hypnotic effect that accents Lester’s loneliness and, too, finely suggests the degradation of morality that comes with isolation. Still, much of this can be said about McCarthy’s novel, if to a slightly lesser extent.

What we return to, then, is that the biggest issues with Child of God are those largely inherent with trying to bring it to the screen in the first place. As is often the case, the prospect of a difficult adaptation convinces the filmmaker to stay more faithful to what came before — and, indeed, Franco makes only a couple of changes to the plot. One of those (involving the aforementioned stuffed animals) is perhaps the film’s highlight, and the entire film plays up implications of that change, including making this Ed Gein-inspired figure far less horrifying and far more pathetic than McCarthy’s. That change, alone, suggests a great deal beyond what the novel does, and, although it does not quite grasp these compelling changes and roll with it, simply finding them in such literary source material makes Franco’s Child of God a success, even if it may be a qualified one.

Child of God screened at the 2013 New York Film Festival and is awaiting U.S. distribution.