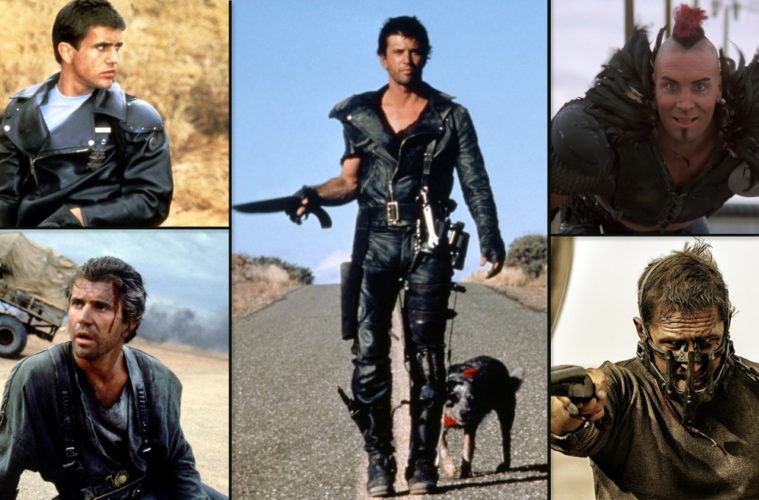

Returning to both the Mad Max franchise and action cinema in general this Friday after a 30-year absence, today we are taking a look at the films that launched George Miller’s career. Before our review of Mad Max: Fury Road, Jared Mobarak has explored each film in the Mel Gibson-led original trilogy, so check out his thoughts below and let us know your take on the films in the comments.

Mad Max (1979)

You couldn’t turn on the television without seeing Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome when I was growing up. I couldn’t tell you anything about it besides the fact Tina Turner co-starred, but I remember the whole terminally crazed aesthetic of George Miller‘s post-apocalyptic world. So much so that I always assumed I had seen the two previous entries. While I’m pretty sure memories of The Road Warrior lie somewhere dormant in the back of my mind, I cannot say the same about the original. The yellow “Pursuit” vehicles? Rockatansky domestic life of love and smiles? Baby-faced Mel Gibson trying his damnedest to not become one of the riff raff his badge affords him the power to take down? Nope. None of it rung a bell. So maybe I entered my first viewing with too high of expectations.

I knew Mad Max was a low budget independent that somehow struck a chord with international audiences to make it the most profitable film in history before getting unseated by The Blair Witch Project in 1999, but I underestimated exactly how dated its low-fi sensibilities had become. The product of a former medical doctor in Sydney (director Miller) and a burgeoning filmmaker (co-creator Byron Kennedy) who met at a summer film class almost a decade prior, this unlikely hit debuted in Australia on the heels of a sub-$500,000 production. Scribed by Miller and James McCausland, the hyper-violent look at a dystopian future where crude oil is scarce and the roads riddled with outlaws sold for $1.8 million on its way to grossing $100 million worldwide. Talk about a dream come true.

I can’t speak to how it would have been received upon release, but today its hard-R is tamed by its cheesiness and lack of meaningful plot. Not only does the camera refuse to show any of the carnage besides a severed arm and shot-out knee-cap (oh, I shouldn’t forget the odd frames of buggy bloodshot eyes right before two key deaths by car crash explosion), the filmmakers’ attempt at romance comes courtesy of Max’s (Gibson) wife Jessie (Joanne Samuel) playing the saxophone and him bopping her nose with greasy hands while fixing their wagon’s fan belt. The action is almost completely filmed in close-up montages of static car fixtures, cars and motorcycles alternate possessing superior speed of the other depending on what currently suits the script, and Max doesn’t even get “mad” until Act Three.

Hell, there isn’t really a story until Max hits that breaking point—the other two-thirds is merely prolonged exposition. And even that’s shared in as obtuse a way as possible considering we don’t know about anything besides the fact crazy people are crazy and the police officers meant to stop them are barely one notch lower on the insanity scale. This provides some great comic relief, especially at the beginning with an overly enthusiastic dolt in Officer Roop (Steve Millichamp) and his green partner Charlie (John Ley). Between the comedy of errors these two undergo, the maniacal fit of laughter via the criminal they’re pursuing (Vincent Gil‘s Nightrider), and the abstract shots of Max stoically waiting to intercept the chase, I couldn’t stop rolling my eyes at the sheer goofiness of everything juxtaposed together.

And what was it all for besides giving audiences a couple of annihilating car collisions? To make sure Max is put firmly in Nightrider’s boss Toecutter’s (Hugh Keays-Byrne) crosshairs of course. At least that’s the original motive despite this psychopath going after Max’s best friend and partner Goose (Steve Bisley) instead. In fact, I’m not even sure Toecutter knows Max is Max when they finally do confront one another. I was surprised Max knew he was Toecutter when asking a shady mechanic for information considering he was only looking for the guy who threatened his wife and child. Yes, even though Miller and company makes a huge deal about Toecutter moving hell and high water for vengeance on Rockatansky, the reason they find themselves in the same frame at the climax is sheer dumb luck.

Story contrivances aside, at least the characters are memorable. If anything, Max Rockatansky proves the most boring of the bunch if not for his tragic circumstances setting him up to be much more interesting (and mad) in the sequel. Police Chief Fifi (Roger Ward) is a hoot, Bisley’s Goose is a raw nerve ready to wield a baton and go on his own rampage, and how can you not love the simpleton Benno (Max Fairchild) ambling about? Tim Burns‘ Johnny is schizophrenia incarnate, Geoff Parry‘s Bubba is a stone-cold killer, and Keays-Byrne a charismatic villain whose demise is sadly anti-climatic enough to forget it happened. The rest are Keystone Cops and hillbilly rednecks guffawing their way to early graves. Good guys wear shiny leather and the bad are shrouded in weatherworn hide.

I wish I could have watched it through the eyes of a 1980s kid not already desensitized to on-screen violence let alone the off-screen variety utilized here because Mad Max does read as special on paper. A handful of nobodies behind the camera and an anonymous Mel Gibson in front (American trailers focused solely on the action) took Australia and the US by storm before spawning two follow-ups in five years and a fourth coming after thirty more. I can see the potential it would bring to fruition because potential is this film’s sole commodity. Since the fierce anger behind Max’s eyes that sold tickets in the first place is absent until the final frame, the rest plays as though Part Two was inevitable. Presently it appears that sequel is exactly what makes it worthwhile. [C]

Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior (1981)

Welcome to the “Wastelands.” This is the Mad Max I remember—a desolate post-apocalyptic future riddled with mohawk-toting, S&M leather-wearing marauders bearing teeth and chaining submissives/human guard dogs on leashes until the fight needs some extra wild. It’s no surprise Hollywood changed the name from Mad Max 2 to The Road Warrior before release while refusing to call attention to it being a sequel in promotional materials because it’s a different beast altogether. With Mad Max‘s unparalleled international success positioning George Miller to choose his next project, foregoing other inklings to revisit the violent Australian outback with a larger budget allowed his vision to reach its full potential. All remnants of police order were expunged, the no-holds-barred life on the road increased exponentially as it took center stage, and Max (Gibson) was officially left with nothing.

The introductory narration by Harold Baigent—while supplying straightforward answers for what went wrong in the world rather than leaving us to infer the truth (my favorite part of the original film)—made me breathe a sigh of relief as it rendered Mad Max a footnote. I thought I was too hard on that supposed “riveting classic” (New York Times), but the way Miller and collaborators Terry Hayes and Brian Hannant compress its story to a five-minute montage shows how little plot was present. Mad Max proved nothing but an overlong origin story for a man to which we were about to be reintroduced. A cop who lost wife and son to the monsters most of humanity have now become, his rebirth as the “road warrior” was complete. Alone in his Interceptor, he scavenges the desert for survival.

With a decent supply of Meat & Veggie dog food to satiate his and his four-legged friend’s appetite, Max’s main pursuit is gasoline. Fuel became the only form of monetary compensation left and the desire to stock up had turned man cruel and unusual. We saw a bit of this transformation with Nightrider and Toecutter, but they were still men clinging to civilization albeit with animalistic tendencies. Murderers and rapists alike, they hadn’t yet morphed to build a nightmarish army like that possessed by The Humungus (Kjell Nilsson). Only when you leave society and infrastructure fully behind can you devolve into a force of nature. Rather than entering a crumbling city as an outsider, Humungus and his cronies claimed the fringe as their own. There it’s the kind-hearted who are invaders and the home team takes no prisoners.

So when a rag tag bunch of nomads plants a flag in the sand like Pappagallo’s (Michael Preston) fellow settlers around a still fertile pocket of crude oil, Humungus’ “warrior of the wasteland and ayatollah of rock-and-rollah” takes umbrage. Max isn’t interested in the impending war between these two factions, he merely wants to fill his gas cans and be on his way. Unafraid to kill the horror-movie dirt-bike vandals—he’d love to put a bullet in the head of loose cannon Wez (Vernon Wells)—he knows diplomacy is his best avenue. He sits back as Wez and a few of Humungus’ other soldiers rape and beat two of Pappagallo’s scouts, biding his time until he can eventually swoop in to save one of the victims and hatch a deal for gas in return.

This of course puts him inside the compound just as Humungus returns to bang on its doors. Blood is spilled, fire is thrown, and Max reluctantly joins the settlers in order to sweeten the pot of his spoils. The plot is therefore very easily packaged in good versus evil compartments, but when you look objectively you’ll see there isn’t really room for such labels in this new world. Both sides are killers; both sides merely wish to live—their extracurricular proclivities becoming the main detail separating them from one another. And Max in the middle might be the worst of them all because he has no motive other than himself. The settlers fight for the future, Humungus for the present pleasures. Max simply wanders because he has nowhere to go and no sense of hope to sustain him.

He’s the antihero we watch and wonder about. Will he finally break and become as bad as Wez and the others or will someone like Pappagallo, his Warrior Woman (Virginia Hey), or the not-so-innocently young Feral Kid (Emil Minty) save him from the void? A choice like this can never be easy for someone who has endured what Max has, though, and Miller never even attempts to pretend it can. Instead he brings in another stranger with the Gyro Captain (Bruce Spence), a happy-go-lucky optimist flying around the desert without a shred of malicious intent to go with his surprising cunning. His inclusion allows the filmmakers to keep Max as stoic and dour as possible while not rendering the movie so painfully dark that we lose interest. Gyro’s comic relief and heart keeps Max’s ambivalence authentic by contrast.

How Max and the rest of the “not-so-bad guys” are painted with a three-dimensionality for us to accept their plight and condone their actions is a vast improvement over the sentimentality of Mad Max‘s characters sleepwalking through a contrived existence. But it’s the reworked aesthetic that stands out most to make The Road Warrior a science fiction classic where its predecessor fell short. The action is shot with more excitement (seeing vehicles roaring in the distance through the window of Max’s vehicle is an exhilarating feat); gruesome injuries are graphically shown (for the most part since edits were made by Australian censors before even the MPAA got involved); and the costumes finally vault what’s onscreen out of contemporary times. Where Mad Max was a dressed-up 1979, The Road Warrior has become a completely different universe.

A playground of carnage, it exists as a product of 80s sensibilities. Wez is a hair band brawler while The Humungus’ masked face makes him a punk rock Darth Vader. Even Pappagallo’s crew is steeped in the decade with padding that looks like they raided a jai alai locker room. Because they, their vehicles, and the environment have been ravaged by death, dust, and destruction, however, what we see exists beyond time. Miller’s moved beyond characters that lived before and after by introducing children inside his new world order. So while the plot is an Alamo-like last stand, the film delivers much more through its visuals and performances. And with Happy Feet‘s abhorrent diatribe politicizing our youth in the guise of entertainment, this is obviously Miller’s idea of Earth’s future—our future—above any imaginative fantasy. [B+]

Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome (1985)

It’s said that Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome is based (without credit) on Russell Hoban‘s science fiction novel Riddley Walker. This could be true, but to my eye the finished product bears a striking resemblance to the 80s fantasy aesthetic thus far utilized during the decade. More of a parallel than to its own predecessors: low budget 70s cops and robbers actioner Mad Max and gritty dystopian epic The Road Warrior. Its first half in Bartertown is the Wild West of Star Wars‘ Mos Eisley with an underbelly of slave labor a la Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom while the second proves a cross between the lifestyle of Return of the Jedi‘s Ewoks and Peter Pan‘s Lost Boys. It looks great, is an adequately relevant evolutionary step forward in the series, but thematically a whole different beast.

While remembering very little, I did watch this installment a lot as a child. However, understanding its not so subtle messaging about alternative fuel sources—the methane in pig manure running an entire city in the middle of a wasteland twenty years removed from the happenings in Mad Max—was an impossibility in the late 80s. To me Thunderdome was a cool looking futuristic world with goofy wardrobe and Tina Turner belting out lines like she was on stage in front of a sold-out crowd. Don’t get me wrong, it’s not as blatant a metaphor as Happy Feet—there’s no UN council debate interludes preaching—but it’s nonetheless a very visible point of interest beyond its purpose towards plot. If necessary to the story, Max’s (Gibson) climactic return to save The Master (Angelo Rossitto) would mean something.

As it is now, when Max and a handful of nomads leave their desert camp of devotees—believers in a “Captain Walker” returning to his crashed plane to save them by flying to the “high-scrapers” of “Tomorrow-Morrow Land”—to save Savannah Nix (Helen Buday) and her band of overzealous followers, they could run anywhere for safety. Max only needs to return to Bartertown—a hotbed of criminals with a Thunderdome battleground where “two men enter, one man leaves”—on a one-man covert job to steal a vehicle. Retrieving The Master is hardly an act Max’s conscience covets or something necessary for survival. That’s not entirely true since the diminutive man’s a genius who manufactures energy, but he’s already been shown as a horrible monster. The assumption should be that he’ll eventually turn power-hungry again, not become a savior.

But that’s exactly what’s wrong with co-director George Miller (friend and colleague George Ogilvie assisted via a working relationship the two developed on a miniseries together) and co-writer Terry Hayes‘ script. There’s very little happening that has any bearing on the rest. It’s two separate stories cobbled together by an unnecessary journey for added action. The adventure at Bartertown where Max enters into the employ of aboveground leader Aunty Entity (Turner) to murder below ground counterpart Master and Blaster (Paul Larsson supplies his “brain” a brawny body with which to move as a God) ends in a dire situation of his own. His inevitable defeat of fate is enough of a key closure point to the thread that it makes more sense to never go back. We’re ultimately thirty minutes removed from Aunty’s chaos before her city’s mentioned again.

This is because Savannah and Slake’s (Tom Jennings) secret dwelling of feral children and Scrooloose (Rod Zuanic)—a Day of the Dead lover—is introduced as a coherent premise in and of itself. They know nothing of Bartertown or the world long since destroyed by the oil wars. They only know the prophecy of an airplane pilot who promised a return. He’s their God, his words scripture. They hope Max is his second-coming, but he’s way too cynical to ever pretend being more than a scavenger watching his own hide until the lawman conscience within refuses to transform him fully into a terminally insane wild man. The only reason I see for going back into the belly of the beast, besides needing water, is so Miller can shoot the requisite road war we’ve thus far been without.

Because that’s the franchise’s calling card, right? I’m certain many people felt jipped when the plot turned sentimental rather than “mad.” Maybe Miller hoped to take his vision a different direction with more stories planned about a rebirth of society, removing any connection to Road Warrior in the process. He did give Bruce Spence another role so similar to the one he played in the last film—Jedediah the Pilot instead of Gyro Captain turned leader of the jai alai-wearing wanderers—that refusing to give either he or Max a moment of recognition is shocking. I don’t know how you could provide a more confusing start than having an old friend swoop down and steal Max’s stuff, make sure he clearly sees him inside Bartertown, and never say, “Max! Is that you?” I thought I was missing something.

Nope. As with Road Warrior, the series’ only constant is that Max was a cop who watched his wife and son get murdered by a ruthless gang of thugs. Everything else is free from mythology so Miller and company can do whatever they wish with the plot. They decided this installment would make Max into a bona fide hero who leads an entire group from the clutches of death. So they created larger-than-life villains in Master/Blaster, Aunty, and random crazies like Angry Anderson‘s Ironbar as well as wholesome innocents in Savannah and her wards. It’s a ton of fun out of the gate before slowing to a crawl with the cult of “Lost Boys,” finally revving back up for a centerpiece car chase of implausible explosions and a weirdly benign conclusion proving Thunderdome nothing more than a nostalgic curio. [C+]

Mad Max: Fury Road opens on Friday, May 15th.

What’s your favorite film in the original trilogy? What are your thoughts on it overall?