With 2013 wrapped up last week thanks to the unveiling of our top 50 films of the year, it’s time to turn our heads to 2014. Before we let loose our rundown of most-anticipated films, we’re taking a look at the noteworthy titles we’ve seen at festivals that will finally see a release in 2014. While the list below includes a handful of undistributed titles, we’re hopeful that they’ll pick up acquisition in the coming months and arrive in theaters by the year’s end.

The below thirty films are also only a portion of what we’ve seen; other notable (and not-so-notable) features include the Jude Law comedy Dom Hemingway, Jason Bateman‘s directorial debut Bad Words, Alexandre Aja‘s Horns, Ti West‘s The Sacrament, the crime drama Blood Ties, Atom Egoyan‘s Devil’s Knot, Eli Roth‘s The Green Inferno, Can a Song Save Your Life (from the director of Once), The F Word, the Jimi Hendrix biopic All is By My Side, Jimmy P., Adult World, The Pretty One, Afflicted and Trust Me. Note that the list doesn’t include Hayao Miyazaki‘s The Wind Rises, which would be near the top, but it technically was (briefly) released in 2013 for awards qualifications. Check out the thirty films below and let us know what you’re most looking forward to in the comments.

30. R100 (Hitoshi Matsumoto; TBD)

What do you get when you cross one of Japan’s most influential comedians, a premise similar toThe Game – but with a zany wild streak of subversive humor — and a whole lot of S&M? The answer is Hitoshi Matsumoto‘s R100, a film following the mild-mannered Takafumi (Nao Ohmori) as he descends into a world of painful pleasure, the likes of which he wasn’t prepared. Similar in tone to his previous film Scabbard Samurai, I fortunately didn’t have to worry about bridging the cultural divide for complete coherence like I did there. It’s not because this one was made with a Western voice or possessed a stronger story, however. No, there was little struggle to figure out what was going on because Matsumoto decided to purposely go as absurd as he possibly could. – Jared M. (full review)

29. A Field in England (Ben Wheatley; February 7th)

“A coward becomes a man” is, I suppose, the crux of Ben Wheatley’s newest thriller, A Field in England. We find Whitehead (Reece Shearsmith) hiding in the bushes while mortars explode around him during battle, weeping and praying to God to keep him hidden now that his mission (finding an elusive old comrade) seems all but futile and far too dangerous. He runs, meets a few other deserters in a mid-17th-century English Civil War pitting the Parliamentarians against the Royalist monarchy, and moves forward towards a chance at prolonging his life while, along the way, martyring himself for personal failures. A scholar amongst blue-collar men, Whitehead’s chance to prove himself once more comes courtesy of a serendipitous stumbling upon the object of his search in an overgrown field. Chaos ensues. – Jared M. (full review)

28. Starred Up (David Mackenzie; August TBD)

In an opening sequence, as he’s arriving to adult prison, Eric (Jack O’Connell) is given a thorough inspection in a moment that clues us in to the kind of movie Starred Up will be: a no-holds barred, explicit exploration of prison culture. Directed by David Mackenzie (Mister Foe, Perfect Sense), Starred Up is a more extreme and, often, more exciting exploration of themes MacKenzie has previously tackled. Eric, a violent drifter of sorts, grows up without a proper parent, learning to fend for himself — and, in a later scene, we learn the exact consequences of this and how it got him to this present state. Eric, for the first time in his adult life, meets his father, Neville (Ben Mendelsohn), a hardened criminal who encourages his son to play the game. A product of the “system,” he wants Eric to simply go along, keep his head down, and get out. Needless to say, it’s an irritation when his son starts making connections and plans. – John F. (full review)

27. Tracks (John Curran; May 23rd)

A stunningly beautiful film, director John Curran‘s Tracks traces the physical and psychological 1,700-mile trek of Robyn Davidson (Mia Wasikowska) from the central Australian town of Alice Springs to the Indian Ocean. As masterfully shot by Mandy Walker, the film has images that, at times, are lucid, while its structure and Curran’s direction takes little risks. Inspired by an award-winning 1980 account (expanded from a National Geographic article published in 1979), Tracks allows us to share a journey that shaped Robyn, an awkward young woman who survived in Alice Springs doing odd jobs in exchange for a camel. – John F. (full review)

26. Run & Jump (Steph Green; Jan. 24th)

While this past fall saw the release of Nebraska, a dramatic effort from Saturday Night Live‘s Will Forte, it wasn’t his first. Earlier in 2013, Tribeca Film Festival hosted the premiere of Run & Jump, which features the actor in a supporting role. As we said in our review, it’s a film that will grow on you, slowly and subtly absorbing you into its world. With an observant structure, we are the third wheel in a tested marriage, following an American therapist, Ted (Forte) who arrives to a Ireland to document the recovery of Conor (Edward Macliam), a family man whose suffered a stroke. ” – Jordan R.

25. Venus In Fur (Roman Polanski; June TBD)

Even in an advanced age and with a slightly reduced rate of output, Roman Polanski is still considered one of the most influential filmmakers alive and operating. His previous film, Carnage, was adapted from a piece of theater by scribe Yasmina Reza and is constrained to a single interior location; following suit with similar meta-theatrics, Venus in Fur is the second adapted play for Polanski, this time taking from playwright David Ives‘ tale about an actress auditioning for a dominatrix-inspired role. Turning this into what could have easily been titled Fifty Shades of Polanski, he examines the roles of sexuality between a man and a woman. – Raffi A. (full review)

24. Mistaken For Strangers (Tom Berninger; March 28th)

Emerging as one of indie rock’s most acclaimed acts in recent years, the Brooklyn-based band The National were the subject of a 2008 documentary titled A Skin, A Night. Directed byVincent Moon, the hour-long film took an aesthetically stark look at the formation of the previous year’s album Boxer. Two records and a great deal of success later, the band is now the subject of another documentary and one that couldn’t be any more different. – Jordan R. (full review)

23. Abuse of Weakness (Catherine Breillat; Awaiting Distribution)

The draw of Catherine Breillat‘s newest, autobiographical film, Abuse of Weakness (known as Abus de faiblesse in its native tongue), is ultimately to watch how someone so desperately in need can be preyed upon no matter their own intelligence, wealth, or stature. When tragedy strikes, unannounced, via a debilitating stroke, the fear of death and paralysis eventually leads to newfound tenacity and strength — but what no one who isn’t absolutely indebted to the help of others for even the most menial tasks (such as opening a door) can know is that the simple act of showing up may prove all-powerful. A friend with the rare quality of not tainting every kindness with a healthy dose of pity is everything. When that person is the only one taking the time to call and visit each day, you can’t really be blamed for doing whatever possible to repay the favor. – Jared M. (full review)

22. Visitors (Godfrey Reggio; Jan. 24th)

We can think of few better ways to ring in the New Year than experiencing a new film from Koyaanisqatsi director Godfrey Reggio. His first feature in over a decade, Visitors looks to have a smaller scale than some of his other work, shot completely in black and white. While our TIFF review was mixed, I look forward to seeing it myself on the big screen. – Jordan R.

21. Borgman (Alex van Warmerdam; June 6th)

The less you know about Borgman, the better. All that matters is that it’s Dutch, it was the most bizarre film to play in the main competition of Cannes this year and it’s coming out next year courtesy of Drafthouse Films. Oh, and it’s a devilishly good time for fans of black comedy shenanigans. If any of that sounds at all intriguing, then definitely seek this film out and you’ll be sure to be both bewildered and delighted. All that’s left to say is: Gotta go Borgman. – Raffi A. (full review)

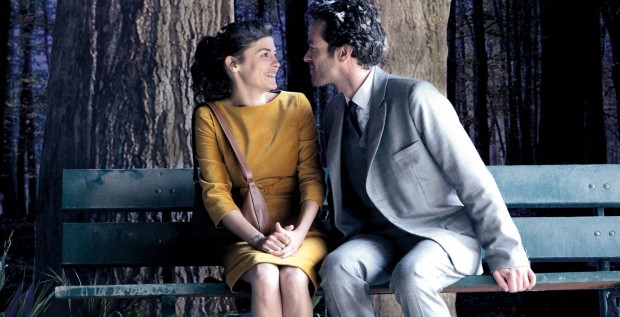

20. Mood Indigo (Michel Gondry; July 18th)

Whether it’s on account of the visual flair he showcases in this hyper-stylized alternative universe or, perhaps, through the frank manner some characters talk to each other, whimsical is the perfect adjective to describe Michel Gondry‘s latest film, Mood Indigo. Wild colors pepper the first half, and there’s an intense level of fun to be had throughout — but it’s not just visual flair. As we fall for our two leads, Chloe (Audrey Tatou) and Colin (Romain Duris), their profiles are intricately constructed. The latter, an extremely eligible bachelor, has a full-time lawyer who cooks for him in his wacky trailer apartment, never working because he has plenty of money. – Bill G. (full review)

19. Blue Ruin (Jeremy Saulnier; April 25th)

92 minutes of taut physical activity, morbid humor, and gruesome violence, Jeremy Saulnier’s Blue Ruin is one of the year’s leanest and most impressive killing machines. Saulnier begins his film with quiet, character-building chapters, but once he sets his resourceful, pleasingly narrow plot in motion, Blue Ruin becomes nothing more than a series of sharp, vicious set-pieces founded on Nash Edgerton-like bursts of violence. The film is a good example of the kind of genre treat that gets points for disposable ambition: Saulnier’s technique is so controlled, and his sequence staging so clever, that nothing else really matters. – Danny K. (full review)

18. The Finishers (Nils Tavernier; Awaiting Distribution)

Finishers is a wonderful, crowd-pleasing tearjerker, inspired by the real life Hoyt Family. Starring Fabien Heraud as Julien, a 17-year old with congenital palsy, he gravitates towards his mother (Alexandra Lamy) while his relationship with his father Paul (Jacques Gamblin) has remained distant. After several attempts, Julien convinces Paul to carry him on his back for the grueling Iron Man France triathlon. Packing a physical and emotional punch, Finishers (currently without a US distributor) is a first-rate family sports drama that left not a dry eye in the house when it premiered at TIFF. – John F. (full review)

17. Grand Piano (Eugenio Mira; March 7th)

Rarely does a hostage thriller go so far off the rails and, yet, remain genuinely refreshing all at once. Appropriately, Grand Piano, the latest film from director Eugenio Mira, almost feels like a dare taken to its full conclusion — because, even with a significant skillset, how one can make playing the piano a thrilling and wild event? Answering this question paves the way for a truly filmic picture that embraces the chaos of reality and how well-laid plans can consistently disintegrate once the human element is added. – Bill G. (full review)

16. Young & Beautiful (Francois Ozon; April 25th)

Jeune & Jolie (Young & Beautiful) paints the portrait of a young French girl’s journey of sexual awakening and experimentation that is at times reminiscent of a teenage version of Luis Bunuel‘s Belle du Jour. Often melancholic but interspersed with some unexpectedly funny candid moments, French director Francois Ozon presents an non-judgmental voyeuristic peek into the life of an underage prostitute. – Shanshan C. (full review)

15. The Double (Richard Ayoade; May 9th)

Comically dry like director Richard Ayoade‘s debut, Submarine, his sophomore effort takes more than a few steps towards an even more arid realm of complete existentialist surrealism. As adapted by the helmer and Avi Korine, The Double brings Fyodor Dostoyevsky‘s novella to the big screen with a surefire confidence in its visual form and an eccentric comedy that should go a long way towards securing the IT Crowd star as a permanent, unique voice in contemporary cinema. There is a definite stylistic kinship to his first film, pairing it well with this one’s descent into a psychological conflict of identity: every waking second of Simon James’ (Jesse Eisenberg) entire existence shatters with the introduction of a confidently superior doppelgänger named James Simon. – Jared M. (full review)

14. The Strange Little Cat (Ramon Zürcher; Awaiting Distribution)

Running a brief 72 minutes, The Strange Little Cat joins the hour-long Viola as 2013′s second feature that will require multiple viewings, but ones which will pass by briskly and pleasurably so. Its aesthetic gambits are at once obvious and yet perplexingly complex, its tone a playful register mixed with sudden moments of melancholy, and its narrative at first shallow, but soon revealed to be densely layered. While some have criticized the Berlin School — the filmmaking movement that has bred terse, methodical directors like Barbara’s Christian Petzold, Everyone Else’s Maren Ade, and In the Shadows’ Thomas Arslan– Ramon Zürcher’s debut feature feels like a bold step towards something much warmer and amiable than any of these noted “contemporaries.” Given the subtlety of its narrative, questions of whether this congeals into something substantial might be up for further debate, but I’m willing to give this unquestionably unique work a very strong benefit of the doubt when the rigor of its filmmaking leads toward so many unexpected pleasures. – Peter L. (full review)

13. Cheap Thrills (E.L. Katz; March 21st)

Every now and then a film completely sideswipes your mental capacities and takes over. Since seeing Cheap Thrills at SXSW, I’ve hardly been able to get the film out of my head. It’s stuck there, jabbing me every dozen minutes and reminding me how much I was in its deathgrip for around 90 minutes. There is very little fat to this work, a good sign, considering I don’t know if I could have taken any more visceral punishment. The stakes, the violence and the intensity were constantly moving higher as each minute ticked away. – Bill G. (full review)

12. The Dance of Reality (Alejandro Jodorowsky; May TBD)

One of the most revered surreal and abstract filmmakers ever to grace the cinematic landscape,Alejandro Jodorowsky holds a deserved cult status. He is most famous for making two films in the early 1970s, El Topo and Holy Mountain, both of which feature some truly shocking imagery that drew comparisons to the early film work of Salvador Dali and Luis Bunuel. However, he has not made a film since 1990, leaving many of his ardent fans wondering if his career was finished. Twenty three laters he has returned with what may be his most personal and straight forward film to date. But fret not devoted fans of Jodorowsky, La Danza de la Realidad (The Dance of Reality) still features his signature avant-garde imagery which pushes the limits of what to expect from the unpredictable. – Raffi A. (full review)

11. Joe (David Gordon Green; April 11th)

While it often feels like a brother to Jeff Nichols‘ brilliant Mud, David Gordon Green‘s newest drama Joe even has the same young actor supporting his titular lead: Tye Sheridan, who either has the greatest agent in the world or, simply, possesses the kind of ingrained encyclopedic knowledge and love for the art form that someone like Paul Thomas Anderson had at the same young age. His résumé may not contain a whole lot of diversity, what with its three country boys growing up the subject of abuse — Terrence Malick‘s The Tree of Life rounding out that trio — but he knows emotional stoicism and unwavering moral centers in a way most adult actors can’t wrap their heads around. He embodies the hardworking boy-who-could-kick-your-butt image perfectly while, too, giving us a troubled soul in desperate need of our compassion and empathy. – Jared M. (full review)

10. Jealousy (Philippe Garrel; TBD)

Due to the constant influence May ’68 has on his work, Philippe Garrel’s films often concern a fruitless pursuit of something lost — and, with Jealousy, maybe the simplest human concept: happiness, is the object of this typically talky trek. Amidst the festival circuit’s plentiful offerings of bloat, whether through glibly provocative subject matter or tired recycling of arthouse aesthetics, the relaxed 77 minutes comes as not only a relief, but a reminder of the power found in simple expressiveness. The best way to say it is that Jealousy feels like a story told only through the very images it requires, the multiple perspectives drawing from Garrel’s own life as a father, lover, and child all made wholly clear. – Ethan V.

9. The Immigrant (James Gray; May 16th)

Set in 1921 New York, The Immigrant is writer-director James Gray‘s sprawling tale of an American dream gone awry. Immaculate production design and stunning cinematography byDarius Khondji evoke the era-appropriate atmosphere in a manner not at all dissimilar fromGordon Willis‘ design of The Godfather Part II. The final effect is a film laden with nostalgia that feels ripped right from the past, making way for its own unique examination of a transformative period in American history. Known for his character-rich stories, Gray weaves a compelling yarn of two Polish sisters who encounter unforeseen complications when trying to immigrate at Ellis island: a parable about what makes the United States a complex paradox of capitalist dreams and hopes held both by everyday citizens and those aspiring to become one. – Raffi A. (full review)

8. Jodorowsky’s Dune (Frank Pavich; March 7th)

Never before has there been a documentary about lost cinema quite like Jodorowsky‘s Dune. Riding off the success incurred by career-defining films in the early 1970s (El Topo and The Holy Mountain), Alejandro Jodorowsky was primed and charged to make his most ambitious film to date, a grand scale adaptation of Frank Herbert’s influential sci-fi masterpiece, Dune. It never happened. From having Pink Floyd agree to the soundtrack, Salvador Dalí in line to play the galactic emperor, and Orson Wells signed on as the villain, Dune’s ensemble of talent was uncanny. But the real inspiration behind Jodorowsky’s Dune is the passion this director has for the love of filmmaking, making it a must-see for aspiring filmmakers and film lovers alike. – Raffi A. (full review)

7. Stranger By the Lake (Alain Guiraudie; Jan. 24th)

With Alain Guiraudie picking up the top directing prize for his latest drama at Cannes, and Cahiers du cinéma recently named the erotic drama the best film of the year, it’s safe to say anticipation is high for Stranger by the Lake. Our NYFF review was also quite positive, saying that the film “has a psychological and atmospheric intensity that doesn’t often make room for light comedy. (Which isn’t to say the film is never funny, but rather that the laughs are almost all underlined by urgent suspense.)” Arriving in a limited capacity this month thanks to Strand Releasing, it’s a must-see. – Jordan R.

6. Like Father, Like Son (Hirokazu Koreeda; Jan. 17th)

Known for his intimately personal style of filmmaking and, often, drawing from his own experiences, there are always tugged emotional heartstrings that permeate the core of Hirokazu Koreeda’s films. With his latest title, Like Father, Like Son, the Japanese director drew from his experience of becoming a father to craft an intensely poignant film about parenthood. Oftentimes heart-wrenching, Koreeda is able to weave a range of emotions by remaining slightly detached and observing the subtle mannerisms of both families; with such great performances from both of the child actors, it’s near-impossible not be bowled over by their struggle to understand what’s happening. – Raffi A. (full review)

5. The Congress (Ari Folman; August 29th)

Trippy, bizarre, surreal and hallucinatory are all excellent adjectives with which to describe Ari Folman‘s The Congress. Adapted from a novel by legendary sci-fi author Stanislaw Lem (Solaris), the film is a hybrid of live-action and mind-bending psychedelic animation; as this is the filmmaker’s follow-up to Waltz with Bashir, those familiar with that title know that Folman is far from a traditional filmmaker. Delightfully surreal and spectacular in its scope, The Congress is a strong testament to the originality and talent behind Folman’s vision of where cinema can take us in the years to come. – Raffi A. (full review)

4. Manakamana (Stephanie Spray, Pacho Velez; April 18th)

Stephanie Spray and Pacho Velez’s Manakamana, the latest work from the Sensory Ethnography Lab at Harvard — most recently behind Leviathan, a TIFF entry last year — is a spellbinding work of humanist cinema, and a rigorous experimental documentary that allows its viewers to breathe inside a unique landscape resting somewhere between nature and technology. If Leviathan did everything in its power to bring us light years from a human experience of the world, Manakamana is our species at its most intimate. The passengers “act” to a stationary camera, which observes their interactions directly, cogently, and, often, delightfully. It’s a tightrope act — in many ways, far more carefully parsed together than the looser structure of Leviathan — but Spray and Velez conceive a travelogue in the vein of Abbas Kiarostami and avant-garde artist James Benning, one which, through its execution, perhaps solidifies the Lab as the most important vanguard trailblazers in contemporary cinema. – Peter L. (full review)

3. Only Lovers Left Alive (Jim Jarmusch; April 11th)

Hipster vampires inhabit Jim Jarmusch‘s Only Lovers Left Alive, an unconventional love story set between the desolate locations of Detroit and Tangier. Utilizing his signature deadpan comedy and idiosyncratic approach to filmic expression, the film will certainly appeal to fans of the director’s more bizarre tendencies. The world of Only Lovers Left Alive practically jumps out of the screen, resulting in an oddly poetic ode to the late-night intelligentsia conversations and music scenes that have fascinated Jarmusch for decades. – Raffi A. (full review)

2. Closed Curtain (Jafar Panahi; June TBD)

I can’t say much more now than I did in my full review, but Jafar Panahi’s Closed Curtain is a thrilling meditation on—literally—the liberating powers of cinema, an exploration of where hope comes from, and a chilling cry for help. What begins as a fiction slowly reveals itself to be a visualization of one filmmaker’s creative process, as well as a more fleshed out exploration of what constitutes a film and how digital technology can impact filmmaking that Panahi examined in his previous work, This Is Not A Film. That this one still doesn’t have a distribution deal is a travesty. – Forrest C.

1. Stray Dogs (Tsai Ming-liang; TBD)

Presumably Tsai Ming-liang‘s final feature, Stray Dogs appropriately sees slow-cinema, an art film “movement” of which he’s considered one of the defining members, at its most extreme. With shots lasting around ten minutes in length — and, more often than not, displaying acts ranging from mundane to outright inactive; in particular, an extended “climax” that’s simply two people looking at a mural — the film could easily be described as “difficult.” Yet while it becomes an even trickier narrative piece by the final third, venturing into the obtuse (or as my interpretation sees it, the afterlife), the film’s emotions are always crystal clear. Tsai’s form doesn’t adhere to the tenets of stylized realism with some distancing anthropology, but displays an intimacy of character, setting, and, above all, time. No wonder we come to look at two still figures as a living, breathing version of the very mural they’re turned to tears by. – Ethan V.

Which of the above films are you most looking forward to?