It’s fitting that, following a year considered by many to be the centenary of Indian cinema, the Bengali director Satyajit Ray — perhaps the country’s preeminent cinematic figure — is continuing to make headlines. 2013 was itself a significant year for the celebrated filmmaker: his 1964 film, Charulata, screened in Cannes as part of the festival’s “Cannes Classics” program; the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences announced a major restoration of nineteen Ray titles, leading to retrospectives at the BFI Southbank in London, the Aero Theatre in Santa Monica, and the Austrian Film Museum; and the Criterion Collection acquired eighteen Ray films for future home-video restoration (1963’s The Big City and Charulata were both released in August).

For its 40th Eclipse box set, Criterion has turned to Ray’s autumnal years, an admirable service for a director whose reputation is so often centered on his early-career output (i.e., the Apu trilogy consisting of 1955’s Pather Panchali, 1956’s Aparajito, and 1959’s The World of Apu). The wandering poetry and stark black-and-white exteriors of Pather Panchali couldn’t be further from the house style represented in the new Criterion set: 1984’s The Home and the World, 1989’s An Enemy of the People, and 1991’s The Stranger are all downright theatrical works, consisting mostly of long, dialogue-driven scenes set in bedrooms, living rooms, corridors, and offices. Ray does hard work to make lively cinema out of these physical constraints (which were instigated after his heart attack in 1983): all three films erupt with color (the costumes, in particular, are both visually dazzling and psychologically expressive), while Ray’s camera, though primarily attuned to his actors’ faces and bodies, produces enough formal variety (zooms, dollies, pans, all doled out at subtle and unpredictable intervals) to sustain a feeling of momentum.

Ray’s involvement with The Home and the World, an adaptation of the Nobel Prize-winning author Rabindranath Tagore’s 1916 novel, stretches back to nearly a decade before Pather Panchali was even released: as recounted in Michael Koresky’s liner notes, Ray first bought the rights to the novel from the Tagore estate in 1948. Ray’s initial crack at the adaptation ultimately wasn’t realized, but by the time he got around to shooting the movie in 1983, the director had formed a deep association with the Bengali writer: Charulata and 1961’s Teen Kanya were both based on Tagore stories, while 1961 also saw the release of Ray’s documentary tribute, Rabindranath Tagore. Set during the aftermath of British Lord Curzon’s 1905 partition of Bengal (which sought to sever the largely Hindu west from the largely Muslim east), The Home and the World is the box set’s only period piece; it’s also the set’s most cinematographically dynamic film, exchanging with regularity cordial interactions in the light of day with suggestive, shadow-heavy nighttime conversations lit only by candle.

Ostensibly a romantic-triangle melodrama transpiring amidst a politically charged backdrop, the film begins by introducing the peculiar marital tension between Nikhil (Victor Banerjee) and Bimala (Swatilekha Chatterjee). A refined gentleman who prides himself on his progressive beliefs, Nikhil encourages his wife to break free of her traditionally subservient role; early scenes show her in the company of a governess, Miss Gilby (Jennifer Kapoor), who teaches her to pour tea properly, play the piano, sing English songs, and wear English clothes. Bimala’s newfound agency and exposure is put to a more substantial test when Nikhil decides to introduce her to his old college friend, Sandip (Soumitra Chatterjee), a powerful leading figure of the growing swadeshi movement, which seeks to eliminate all foreign goods from India. Unmarried, a seductive speaker (“I once considered becoming an actor,” he states), a sly hypocrite (he still smokes a foreign brand of cigarettes), and boasting the reputation of a playboy, Sandip is nothing less than a larger-than-life icon in the eyes of Bimala, who hasn’t met a new man in years, let alone one who’s engineering a revolution.

Nikhil rejects Sandip’s movement — “Swadeshi is for those who can afford it,” he says, defending the poor Muslim merchants who rely on the cheaper prices of imported goods — but Bimala chooses to join up with Sandip, a decision she will later regret. The central motif of The Home and the World, which Sight & Sound’s Michael Brooke calls “Ray’s last out-and-out masterpiece,” is fire: it’s there in the opening image, it’s there at the end, and it’s there throughout the film, in the candles, the bonfires, the torches, and the swadeshi movement that “sets the world on fire.” Though the film takes place in a palace of pillars, chandeliers, mirrors, and stained-glass windows, the movie’s force, as suggested by the title, comes from its ability to suggest the outside world. In a short series of film-ending dissolves, which Film Quarterly’s Darius Cooper aptly describes as “apocalyptic,” Ray uses the barest of images — a woman dressed in white, standing in front of a blank wall — to get at devastating truths that reverberate well beyond the frame.

Five years after Ray’s 1983 heart attack, his doctors finally gave him permission to return to serious, feature-length filmmaking, though with a couple caveats: per Koresky, “he was restricted to shooting on studio sets and could not operate the camera himself, as he had done since 1964’s Charulata (his son, Sandip, took over).” It’s perhaps natural, then, that Ray’s choice of material — the Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen’s 1882 An Enemy of the People — would have roots in the physically confining art form of the stage play. (It’s worth noting here that a good deal of Ibsen’s famous A Doll’s House, written a few years before Enemy, can be seen in Bimala’s tradition-breaking behavior in The Home and the World.) Ray’s film updates Ibsen’s story from late nineteenth-century Norway to contemporary Bengal, suffusing the narrative’s inciting incident (the detection of contaminated water) with an intriguing religious angle.

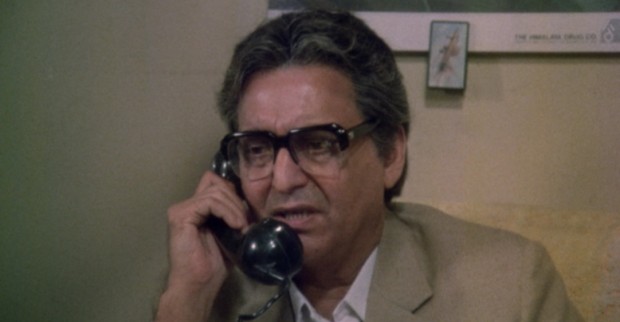

A clean-shaven Soumitra Chatterjee, sporting glasses with thick black frames, reunites with Ray to star as Dr. Ashoke Gupta, a respected physician operating in the small town of Chandipur. In the film’s opening scene, Gupta telephones a local newspaper to report an outbreak of hepatitis. The real kicker comes a bit later when test results confirm Gupta’s controversial theory: the holy water of the town’s popular Hindu temple has been contaminated. The editor (Dipankar Dey) of the newspaper Janavarta assures Gupta that his findings will prove valiant — “Soon, you’ll be a national hero,” he says — but the town’s more religiously inclined inhabitants, led by Gupta’s municipal-chairman brother, Nisith (Dhritiman Chatterjee), are far from willing to believe that their sacred holy water has somehow been violated. That the temple in question is a major tourist destination — and, therefore, something that Nisith is relying on to support the local economy — is another reason why Gupta’s unpopular opinion quickly positions him as an outcast.

The turbulent relationship between the two brothers — the secular doctor on the one hand, the faithful, determined politician on the other — comes to epitomize the film’s core topic of interest: the relationship between science and religion in contemporary Bengal. The film’s opening and closing images, in a bit of visual rhyming that resembles The Home and the World, are both of Gupta’s stethoscope; in between, what that stethoscope signifies is challenged through lengthy, drawn-out discussions in which neither of the two conflicting sides are willing to budge. The duration of these dialogue scenes — a centerpiece sequence at the Janavarta offices runs for about twenty minutes, the climactic public forum about fifteen — speaks to Ray’s physical condition at the time, but it’s also effective in evoking Gupta’s mounting, claustrophobic frustration. Even without having read Ibsen’s play, it’s clear that the optimistic coda is a tacked-on Ray touch; what we’re left with, at heart, is a combative, heated situation that doesn’t appear to have any kind of ready-made solution.

The Stranger, the final film in the set — and the final film of Ray’s career — also gets around to exploring the science-versus-religion dichotomy. Based on a short story Ray wrote in 1981, the film, like Alfred Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt, derives tension from the mysterious, elusive identity of an estranged uncle. Where An Enemy of the People began with a phone call, The Stranger begins with a letter: addressed to Anila (Mamata Shankar, who played Gupta’s daughter in Enemy), the bourgeois wife of Sudhindra (Dipankar Dey, another Enemy alum), the letter is authored rather eloquently by Manomohan Mitra (Utpal Dutt), Anila’s long-lost uncle. After graduating college, Manomohan promptly left Calcutta and gradually lost touch with the family. He hasn’t been seen in thirty-five years, and Anila, who was two at the time of his departure, has no memory of him whatsoever. Anita’s husband is skeptical from the outset: he thinks it’s more likely that the letter-writer is a scheming imposter than Anila’s legitimate relative. (Curiously, Manomohan later encourages such suspicions, admitting to Sudhindra that his valid-seeming passport “proves nothing.”)

A shot of a train speeding across the screen, followed by an image of a passenger reading a newspaper (his face covered entirely by the pages), introduces Manomohan in a delightfully Hitchcockian register. But even though Anila spends her nights reading Agatha Christie novels, this is no thriller: in true twilight-film fashion, The Stranger is meditative, reflective, and leisurely-paced, with Manomohan’s worldly musings comprising most of the action. He boasts about the scope of his experiences: he’s been to Singapore, New York, Machu Picchu, Europe, and even claims to have lived in the forest for five years, away from conventional civilization; he speaks German and French, and tells profound mythological stories; and he speaks of the relative size of the sun and the moon, a digression that recalls Akira Kurosawa’s famous Satyajit Ray quote: “Not to have seen the cinema of Ray means existing in the world without seeing the sun or the moon.”

Ray died at the age of seventy on April 23, 1992; less than a month earlier, he was seen on television from his hospital bet in Calcutta, accepting an honorary Oscar from Audrey Hepburn. Ray’s frail, appreciative, moving acceptance speech was preceded by a clip reel of his work, which The New Yorker’s Terrence Rafferty, writing in May 1992, called “hectic” and “clumsily assembled.” Rafferty continued: “With a filmmaker like Ray, film clips — moments ripped out of the slow-building, lifelike flow of experience that each of his movies seeks to re-create — are worthless. They tell us as little about him as a passport would.” The three films collected in this box set attest to that sentiment: while Ray is still commonly considered a “humanist filmmaker” whose works are “universal,” The Home and the World, An Enemy of the People, and The Stranger reveal a director whose emotional generosity cannot mask a specific, tenacious, unmistakable political urge.

Eclipse Series 40: Late Ray is now available for purchase through the Criterion Collection.