There was something ironic about the worrying that occupied the back of my head as I went up the elevator in midtown Manhattan to Magnolia Pictures’s offices to interview Lauren Greenfield. Already an accomplished still photographer, she has been steadily moving towards motion pictures with a series of short films. Her debut documentary feature, The Queen of Versailles, opened this year’s US Documentary section at the Sundance Film Festival and netted the first time helmer the fest’s Director Award. One assumes that is because “Best Interrogator” does not exist.

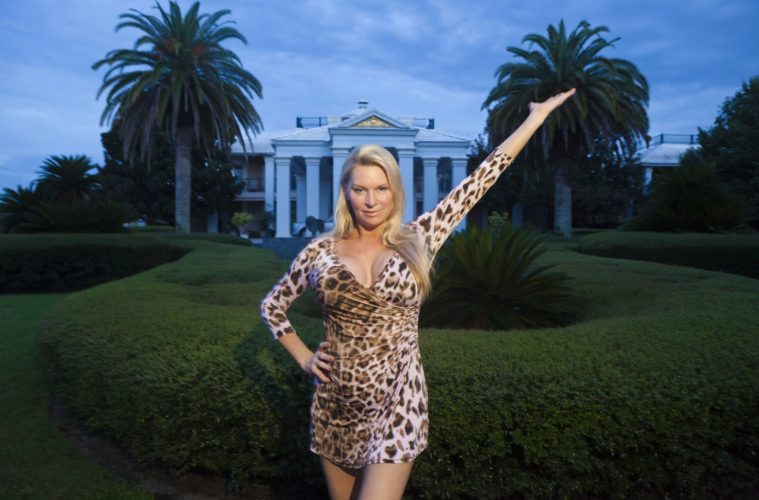

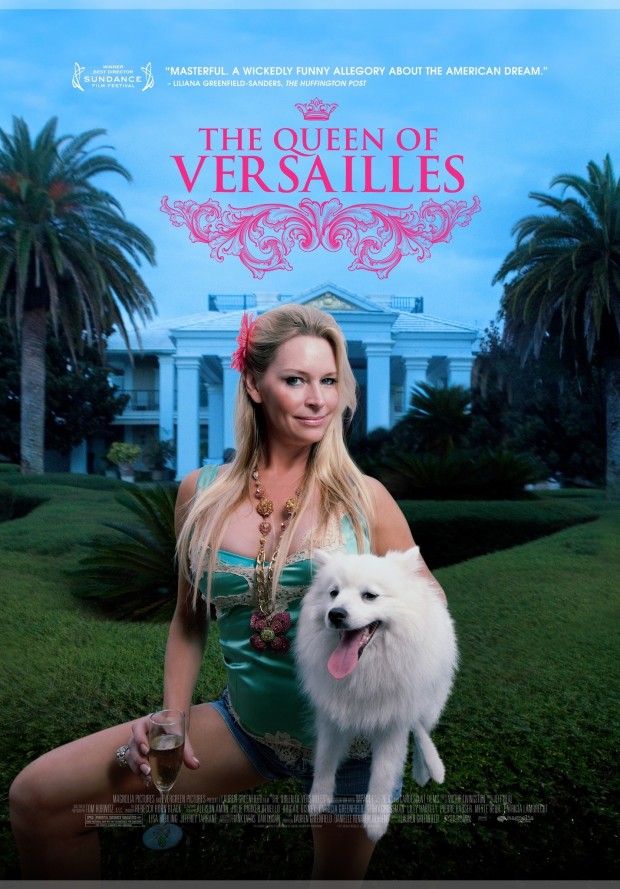

The Queen of Versailles shares the story of one of America’s wealthiest couples, billionaire real estate mogul David Siegel of Westgate Resorts and his wife Jackie as they build the nation’s largest home, cheekily named Versailles. Like the titular ship in Prometheus, hubris clouds the naming process, something evident in the extremely candid interviews that Greenfield is able to capture, even as the housing bubble bursts leaving the family (and their 26,000 square foot “starter mansion”) reeling.

Here I was about to meet this woman after learning an hour or two before that she was being sued by Mr. Siegel over the picture we were about to discuss, which could put a hamper on things. Luckily, Greenfield was as engaging and honest as her subjects, cheerily discussing the allure of film over photography, the dangers of shopping at Costco, how children can become commodities, and finding the bottom. Check out the interview below.

The Film Stage: How is all this press junket craziness as opposed to Sundance?

Lauren Greenfield: Well Sundance was crazy because we went with an independent film. We sold it to Magnolia [Pictures] the first night, and it was, I don’t know, it was really fun, really intense, really crazy. We’ve been working really intensely before then. We finished the film on a Saturday before Thursday night when we opened Sundance. So it was all a blur, but very exciting. I mean, to be the opening night film was beyond belief for me.

How was that in comparison to the usual photography exhibitions?

I feel like film has a much bigger reach. It felt like it was just bigger than anything I had done before. To have Robert Redford introduce the film and the Eccles Theater I think seats 1800 people and all the press Sundance gets, it was just…amazing. Overwhelming and amazing.

With film being so big, was that sort of the impetus for making a photo shoot turn into a full-length film?

No, I think for me the filmmaking process is just really different creatively than photography. Photography [works] where a lot of times I get my ideas, and a lot of times it’s more of a broader essay form, and I’ve been working on this photography project about wealth. I kept thinking about what is that cinema verité story that could help tell the story of wealth. I feel that film has an emotional and experiential element that still photographs don’t have. Also, for me, it’s a way to explore the narrative because my pictures have always been storytelling pictures, but it’s a deeper narrative, and a more longitudinal narrative. It’s just a real creative challenge for me, especially thinking about character development and change over time.

When I was in Jackie [Siegel]’s house the first time, I just felt like it was a film. I don’t know if it’s because you’re moving through the house and the sounds and the characters. There are so many elements there, it just felt like a film that first time. So I continued to take pictures, but we started video taping even the first trip.

One of the things that I loved the most about this movie are the number of narratives that you were able to string throughout the film, specifically the number of children. But my favorite bit was with the realtor, and how you get these little tiny bits of her and how she’s going to sell the house by Christmas time. When you were filming, did you have an eye for those narratives–

–Definitely! The minor characters were always very important to me. Probably, [in] coming from photography, I’m used to be able to having a lot of characters. I find in film in a way you have to focus, so what happened over the course of the project is I realized it’s really David [Siegel] and Jackie’s story. Jackie was always the heart of the story, but in a way, the minor characters were always important to me, and I kind of had to trim them down to become a part of Jackie’s story.

One thing that’s great about their house, and one thing that I loved from the beginning, is that entourage element, where there is always this array of kids and domestic house and different ages and different ethnicities and different backgrounds, so in a way I always imagined the house as being this microcosm of society, and that you can see how different classes, different ages within the house [mix]. One of the things that’s unusual about Jackie and David is that even though they were billionaires when we started, they both had a lot of different people in their world from a lot of different backgrounds, like family members and friends. They didn’t just hang around rich people.

Do you think that’s because of their upbringing and they kept them as they went through their lives?

I do! And also I think they’re just unusual like that because some people, when they become rich, they become social climbers and they don’t want that association. I think that Jackie and David love the stuff [associated with being rich] but she’s not a snob.

The thing about the Christmas party, they socialize with everyone: Cliff the Limo Driver arrives as a guest and Loraine the Real Estate Agent arrives as a guest. When Jackie goes back to her hometown, she brings Loraine with her, so it’s kind of like her real estate agent is her new best friend. At times, [I thought] do I have to explain why the real estate agent is going to Binghamton? Nope! That’s just Jackie’s world, it’s all there. She also has this non-hierarchical relationship with people like Cliff the Limo Driver where they work for her but they’re also friends.

I always thought that was important. After the crash happened, and it became clear that their story for me was an allegory about the overreaching of America and how we were all affected by the crisis, then the minor characters took on that importance, too, in terms of showing how their story relates to what most people went through. Cliff the Limo Driver, the fact that he speculated and bought 19 homes and then lost everything — including his own home — to me, that showed he’s kind of like David but on a different level. The same with Tina, Jackie’s friend from home, and losing her home. And also Virginia‘s story, the nanny from the Philippines who hasn’t seen her kids [in a long time].

That was the most heartbreaking of all of them.

And when I heard that, I thought well, her and Jackie are similar in a weird way because both of them are not really directly parenting because of their financial situations. Virginia is giving up parenting because she thinks she’s doing what’s best for her kids, making money and sending it [back] to them. And when Virginia said that her dream was to built a concrete house in the Philippines, the circle really started to take shape for me.

All of this keeps coming back to addiction. They keep using this term “cheap money,” which seemed to be a nice little allegory for America in general. And if, in fact, the house was an amalgamation of all of America, we’re kind of screwed aren’t we?

I mean, yes and no. The story in a way is a morality tale. When David says, “I should have been happy with fifteen resorts instead of twenty, and if I had been, I never would have needed to borrow money. I could have used my own money.” And I think by the end you realize that Jackie really loves David. You’re not quite sure in the beginning what the basis of their marriage is.

Jackie has also come to terms with what’s important to her: her family, her husband, and that she could live in a small house if she needed to. In a way, those things were not that important to her, so I feel like there is a [returning] to values that you see at the end which is a good message for everybody after the crash; a recalibration of whether or not the things that got us there were really important.

I’m not sure we’re screwed because we don’t have cheap money — not anymore. When gas gets really expensive, maybe we’ll drive less and it’ll be better for the environment. The thing that’s hard is that there’s been so much pain for so many people. Jackie and David have a lot less pain that most people because they started so high, and they’re never going to be homeless.

Cliff’s story is more representative of what most of us went through, and Cliff saw the movie at Sarasota Film Festival with her daughter, and they both were crying during the [screening]. I think that’s the part that we’re screwed in: the pain in the adjustment for so many people. But I think that we had this philosophy before where everybody should have a house, and everybody should lavish themselves. After 9/11, George Bush said people should shop to help the nation and so I feel that it does give us an opportunity to look at those things.

It’s also difficult, as she’s saying these things and doing great charity work giving away items to former employees at her husband’s company, but she still goes to Wal-Mart and comes back with three different games of Operation.

Well that seems to speak to our addiction to consumerism. That’s an extreme scene. It’s almost like madness. But I’ve been to Costco and planned to buy one thing and ended up with a whole cart full of shit that I don’t need. That’s kind of what got us here in a way. Jackie is being well meaning, thinking that Wal-Mart is downsizing, and then ends up with all this stuff. Some of which she plans on giving away, but still, y’know, buying the bike (laughs)

And just the array of bikes at the home. That’s what makes it almost more endearing is that it seemed like she couldn’t really shake the impulse. Especially with David in his little office, that almost coffin-esque room–

–The man cave.

It was even worse than a man cave. Just a depression cave by the end. I found it interesting that he very much valued the business more than the family and how as the business went down so to did the house. Do you think that for him the value of what he built was more important than what he built in his home?

I think he cares so much about his work, and that he’s a total workaholic, and I think that the business was completely consuming for him. He definitely loves his kids. One thing that always surprised me was how he showed up for every single ball game [his children played]. No matter what was going on at work he would just show up at that ball game. But he has a traditional relationship with his kids, from that [older] generation, where he’s not hands on. I think he said neither he nor Jackie had ever changed a diaper. That’s their world.

It was clear to me by the end that the tower in Vegas [Westgate’s PH Towers Westgate timeshare that looms over the strip as well as the film] was more important to him than Versailles [the couple’s 90,000 sq. foot home in Florida], even though he cared about Versailles and he had spent a lot of time on it, it was the Westgate name in lights in the most important real estate in the country on the Las Vegas strip with a sign brighter than any other sign on the strip. Losing that was the most devastating to him.

Especially when tied in to that bit about his parents, how they didn’t have anything, but when they went to Vegas they were a big deal.

And also the fact that they were gamblers, and that even though he was a billionaire put nothing aside, had no safety net.

Do you think that consumerism has been going on in America from the post-war and we’re still feeling the effects of it all the way through? Or was it ramped up recently?

I think it’s been ramped up with the more recent media influence. Advertising has become so ubiquitous and a lot of my photography work has been about that, too. My short film, Kids + Money, is about how money plays into status and identity for kids. I do think as advertisers have directly marketed to kids and as we spend more time in front of screens, it’s all become more intense.

We’ve also sort of based our economy on that kind of consumerism. There’s ultimately an addictive quality in that because you buy something and you think it’ll make you thinner or more beautiful or happier and then it doesn’t, so then you have to buy more. It’s not really satisfying in that way and that’s the thing about living in a 26,000 square foot house and building a 90,000 square foot house.

Jonquil [a child adopted from Jackie’s extended family] is interesting to me as she went from poverty overnight into this big house, she says, “when I used to see rich people on TV I thought they’d wake up with a smile on their face every day and then I realized when I was in this situation you just want more and more.”

There wasn’t a lot of emphasis on the children — Jonquil aside. Was that a choice because they were kids?

It was something that evolved. In the beginning I thought they would be important, then I realized it’s really Jackie and David’s story. In an earlier version, we introduced each kid and it felt like a reality show. When David says, “my wife collects everything. Didn’t want one kid, wanted eight kids.” In a way they became…okay, they have lots of kids, rather than each of their own characters. But Victoria and Jonquil had a character development that made me want to include more of them. They both had kind of amazing arcs, which really spoke to David’s story.

Jonquil, in a way, represented Jackie for me because she came from Binghamton, she came from poverty, but overnight was in this situation, kind of like Jackie’s life, compressed. She is also like the audience in a way. If you got rich overnight, you might be like Jonquil. Victoria kind of made herself more important by what happens in the end because in the beginning she’s this prepubescent, awkward, shy, slightly overweight girl and by the end she’s this beautiful young woman who is somehow self-realized and is the only one who stands up to her dad, and kind of says to her mom, “why aren’t you standing up to him?”

The other kids, you know they’re important to David and Jackie, and they’re part of the whole group, and they’re kind of what makes [David and Jackie] so unusual, that they would have so many kids. But I felt like it was distracting to go in to detail on all of them.

They’re children.

They’re children.

You get the idea.

They’re kind of like the pets: there are so many.

Almost like commodities. Not to dehumanize them, but they’re a part of the house, they come with everything. It’s almost a package deal.

Well Jackie says, “I never would have had so many kids if I could have nannies.”

For me, if I have a large room, I need to fill all that space. They seemed to have the same compulsion. They need a large house, they need to fill it with kids, bikes….

Jackie is in addict. She even says having kids was an addiction at the beginning. She is also full of love. She does love the kids, and she has a lot of love to give. I believe her when she says at the end that if she lived in a small house she’d just put’em all in bunk beds. I think she likes the big house because she’s always full of life in a way.

And that’s definitely reflected in the house, too.

When David says she’s like a child, he’s kind of criticizing her, but she also has this wonderful child-like quality where she makes every day fun. And she did for me. “What’s new today?” We were always running to keep up with her, and she was always, “I’m going here! And I’m going here! And I’m going here! And I’m doing this and I’m going to this charity and I’m going to see these friends!”

How often did you shoot over the course of the, what, two, three years?

I would go every few months for a week or ten days depending on what was going on. Sometimes it would be for an event, sometimes I would just feel like it was time to check in, or when they went to Binghamton, we went there. So it kind of depended.

It seems like the longest you’ve spent with one specific subject.

Yeah.

How was that for you?

It was really amazing because I think you can see in the interviews. I did five interviews with Jackie and five interviews with David and at least two with the minor characters, and you can see this longitudinal progression that’s not just what they say but how they look. More exaggerated because of what they want through. David in three years looks like ten years has passed, and his whole face looks different.

Coming to filmmaking from photography, I’m thinking a lot about portraiture and the interviews were like environmental portraits that kind of spoke to their psychological state of mind as well as what they said. Doing it over time, but also doing it over a really intense time, was a big part of the storytelling. Even with Victoria, when we started she was twelve, and when I show her at the end I actually chyroned her because I was afraid people wouldn’t recognize her. She just looked so different.

Even just the mentality. She was a different person. It took me a bit, but I laughed very loudly when I realized that David was at first in that big throne, and then you see him again in just this normal wooden chair. Was that composition something you thought of going into each interview?

I’m always thinking of the composition of the interviews because in a way I’m working with a DP, which I love doing, but it’s different not being behind the camera. When it comes to the interviews, I’ve got a monitor and I’m seeing exactly the composition which I’m not doing when I’m running around with people.

I think each time I did an interview, I’d try to think of what could capture whatever was going on [with the character] at that time. And also what we hadn’t shown, what room we hadn’t seen. I just didn’t want them to be the same. There are some films where you keep cutting back to the same interview, but here the interviews are really a progression. I kept them more verité and I kept them in order.

At what point when you were making it did you realize that things were going down for the Siegels, and how could you keep them so candid throughout?

The real turning point was when they put [Versailles] on the market, which was in the middle of 2010. So it took a long time after the crash for any changes in their lives. And I think you see at the end when things are going on, you don’t necessarily know about them. Jackie doesn’t necessarily know about them and _I didn’t necessarily know about them so when the house went on the market, it was like, “whoa, things are changing.”

The whole premise at the beginning had been about building this house. At times, I thought it would take too long and I’d never be able to stay with this story but when the house went on the market…. And it wasn’t just [that], in that trip David said he hadn’t put anything aside, there was a lot of stress and strain in the household. It was just clear that [the story] was going in another direction.

It’s hard, because I’m sure you’ve connected with the subjects, but is it a more rich story now that unfortunately everything went down?

I think it became a more important story, because it became more of a symbolic story about what happened to all of us in the crash and not just about this family. And I think they came down to Earth in a way that made them more relatable and more empathetic.

I can’t believe you got them to be as candid as they were and carried that throughout. That shocked me, because they were so open, even David, who looked like it was pulling teeth, but he still gave. Is that part of his personality?

Well they were both incredibly giving. He would always complain and bark and then I’d ask for an interview and then he’d sit down and talk very candidly for long periods of time. The first interview was around three hours. I remember setting up an interview, and this was when things started to really go downhill for them and he went and spent the day at some friend’s river and was just totally relaxing on a Sunday.

He had said we could do the interview when he came back and we were all set up in the foyer and when he came in, he had clearly forgotten. He was in his bathing suit trunks, end of Sunday night, just relaxing, and he was like, “oohh nooo.” And I thought he wouldn’t do it, but I think it’s a part of his work ethic, [that] he respected the professionalism in a way that I brought to it, and we were set up with cameras and lights and everything. He always did it. For all his barking, he has a generous side, too, which is in a way unexpected.

I think the interviews [are] kind of what made me love his character even though he was kind of removed a lot in the verité [sections] and isolated and didn’t really open up much in the verité. In the interviews, to have this powerful man kind of telling you what’s going on was very captivating for me. I think that’s why he became more important in the story because in the beginning I was very Jackie focused.

When the ending came, was that because they were done giving to you or did you figure out that there is no specific end to the story unless they hit bottom?

The two poles for me were the house and the Vegas tower. At a certain point I realized that the Vegas tower was more important to David than the house, and that was the ultimate expression of his success, what he was basically willing to lose everything for. That was a huge revelation when Richard [Siegel, his son and employee] said, “if he gave up the tower, he could have everything back.” And I was thinking, “oh my god, if somebody’s in trouble and you say if ‘you do this, you can have your life back’ would they take it?”

When they lost possession of that tower, that was the end to me. And I didn’t really know if I would finish, because things were happening until the end. My last trip to Florida, David said Versailles was in default, and Jackie learned that it was in foreclosure. I thought that might be the ending. Then they lost possession of Vegas, and I knew that was the ending.

Somebody like David, he’s gone through hard times before, he’s very smart, he will persevere until his last breath. Now that he’s given up Vegas, he’ll build the company back up. I think you know that, and that’s not the important part of the story for me. The important part of the story for me was this morality tale, that he has to give up this building that’s so big and so expensive to make things right.

The Queen of Versailles opens in select theaters Friday, July 20th.