One of the most-anticipated entries into this year’s Cannes Film Festival is / was The Assassin, Hou Hsiao-hsien‘s first feature in several years and his first entry into the territory of martial arts cinema. According to many of those who saw it, ourselves very much included, it lives up to all the anticipation that those details imply.

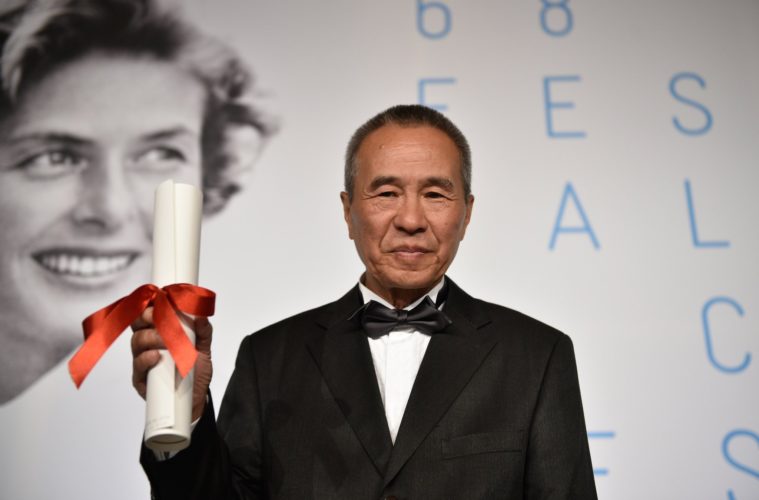

We were fortunate enough to participate in a roundtable discussion with the legendary Taiwanese helmer, who received the distinction of Best Director at the festival. He explained the extended gap between features, how and why his picture differs from many a wuxia entry, the distinction that digital editing makes after the footage has already been composed, and several other essential components of his masterpiece.

Why did it take so long to make this movie? What has been the most challenging aspect of the process?

Hou Hsiao-hsien: I’ve wanted to shoot the film for a long time, but for about 8 years I was occupied with organizing various film festivals in Taiwan, namely the Taipei Film Festival and the Golden Horse Film Festival. At first I only intended to spend 2-3 years on the job, but whenever I realized something’s not working, I’d feel compelled to restructure the whole festival. So I ended up spending 8 years upgrading both festivals and only got to filming The Assassin afterwards.

What made The Assassin so different from all the martial arts movies that came before it?

Whatever film I make, realism is always of critical importance to me. This realism can be staged, but if the footage doesn’t seem authentic enough to me, then I have no use for it — which is why we had to stop and restart filming on The Assassin time and again, making adjustments constantly. The same thing happens again in the editing room. If any given shot doesn’t look real to me — whether technically or in terms of the performances — I’ll just take it out. Only after such a selection process do I even begin to do the edits. So my editing process is not dictated by the script. Even if a shot ends up ambiguous this way, I’m OK with leaving some room for the imagination.

Was making a kinetic, high-flying kung-fu movie never the plan?

I could never have done that. When you’re dependent on too much technical assistance, you necessarily lose control over the film you want to make. The material others present me with is never what I have in mind. Some of the fight choreography originally planned for this movie, for example, was just not what I wanted. What I needed for this movie was something closer to reality, which is the hardest thing to do, because it has to show the force, the impact in a plausible way. And the fights should be meaningful as well. When the action choreographer first described to me how the fight scenes were usually done, I immediately knew that’s not what I was going for. It’s just not something that interests me. To put it simply: the personality of a character should directly affect how he or she fights. Every character has their special qualities, and that should be reflected in the action sequences.

How did you come about picking this character to be your heroine?

The movie is based on a novella from the Tang Dynasty. Back then, they still used classical Chinese to write novels, where each single character meant something, thus enabling them to write really concisely. But even with such a short tale, I only used a part of it for the movie. What interested me, above all, was this character. Her name, Nie Yinniang, captured my imagination. The family name Nie is composed symbolically of three ears. The first character of her given name, Yin, means hidden. And Niang means woman. What I pictured in my mind when I saw the name was this female assassin, hidden from sight, eyes closed but always listening. When she detects sonic changes in her surroundings, she’d open her eyes, leaps out of her hiding place, and in one whoosh finishes the job. Little did I know, then, that Shu Qi is afraid of heights and could never jump down from treetops, so we had to modify that.

The imagery of the movie is exquisite and breathes with such life. Could you talk about how you achieved that technically?

We used a lot of silk for the production. Back in the Tang Dynasty, they used a lot of partitions in forms of drapes and curtains. Even just a normal bed is often separated by screens. And these were basically all silk-based in material. My art director bought huge quantities of silk from Korean and India, picking the material according to what’s envisioned in the script. The great thing about silk is that, when shot in a certain light, it looks just beautiful. This is a major factor for the look of the film.

Did you shoot this movie on film or digitally?

I shot it on film — using over 500,000 ft of it. But I needed to convert it into digital form afterwards, because all the post-production equipment these days only works digitally. Color grading on digital print turned out to be a completely different thing, which cost me a lot of time to learn and experiment, and I still think the quality of the result isn’t as good as it was in the pre-digital age.

Does your long-time collaborating DP, Mark Lee Ping-bin, have a preference regarding film vs. digital?

We both prefer film, which is why we shot on film, but the post-production technology in Taiwan is still not up to par.

The idea of you doing a wuxia movie raised eyebrows. How do you think this film fits into your body of work?

To me it’s still the same as my previous work, because ultimately it needed to pass the test of my eyes. If something looks fake or flawed to me, I won’t use it. If the lighting in a scene is off, I won’t use it. I don’t even care that much about continuity. I have my own way of patching it all together, which is why this film might strike some as oddly discontinuous. Actually I was worried that my foreign investors wouldn’t be able to understand The Assassin, considering the way it was edited together. But it seems that they got it just fine. Then it’s all good.

The Assassin will be released in the U.S. by Well Go USA Entertainment. See our Cannes coverage below.