Because it is timeless, and that statement is more or less inarguable. I recently watched it yet again in a film class. At first I was a little aggravated about it. After all, it just feels like an easy movie for a film professor to put on and just say “watch this!” Part of me wanted to yell, “c’mon man! do your job.”

However, about 5 minutes into the film these thoughts stopped. Orson Welles’ masterpiece speaks as loudly now as it ever did. In the midst of the worst recession since the Great Depression, Citizen Kane serves as a filter into the mind of “the American” and the dream that fuels him/her, not once shying away from the blatant contradictions that define this country’s laurels.

Charles Foster Kane grows up poor, living in a simple rural world. He is then given wealth and opportunity, for a price: the loss of his mother and father. This scene alone both symbolizes and foreshadows the rest of the Kane story, right down to the visuals, Welles employing a large depth of field to illustrate the growing distance between son and parents.

The result of this sacrifice is a chance at unhindered capitalism via Kane’s endless wealth. He is young, handsome and savvy. But, most importantly, he appears to be compassionate, spouting his concern for “the working man” towards the beginning of the film. And, in the beginning at least, it feels genuine and most likely is. After all, Kane is a man coming from nothing who has been given everything. Is that not who we want running our country?

Of course not, because the key word in that sentence is “given.” Abe Lincoln earned his eventual political prowess through compromise and confidence; George Washington earned it through peak battlefield strategy. Kane earned nothing to gain his wealth, and yet his wealth was all he needed to gain power.

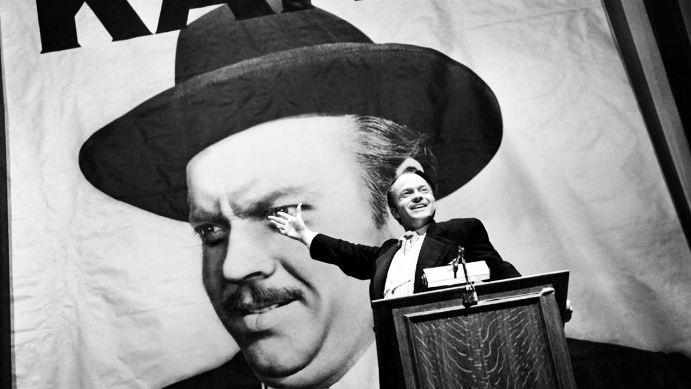

But that fact, alone, does not make him the bad guy. In many ways, Kane is a very likable character, determined to do right. What follows this introduction is the devolution of morality when next to the evolution of monetary ambition. Kane becomes politically-inclined, running for governor and spouting flawless, epic rhetoric that elicit thunderous crowd response. The “political speech” scene (in which KANE and a large photograph of the man monopolize the background of every shot) is one of the most transcendent moments in the film. After all, when was the last time YOU saw a young, ambitious, inexperienced politician making LARGE speeches to LARGE crowds, criticizing incumbent politicians for lingering mistakes?

This is not to suggest that President Obama will become corrupt and heartless, dying alone with only childhood memories to comfort him, but rather to illustrate Welles’ vast achievement with the Kane character. At the time of the film’s release, Charles Foster Kane was an American businessman most closely resembling newspaper mogul and yellow journalist William Randolph Hearst, who was similarly given his wealth (his father was a self-made man). Now-a-days, you could compare Kane to Fox magnate Rupert Murdoch, Ken Lay and Bill Gates, depending on what part of the film you were watching.

Kane represents the thin line between good and bad business in an America that promotes cutthroat capitalism while it promotes nationalistic compassion. If making enough money to “speak for the working man” requires manipulating the working man temporarily, do the ends justify the means? What if said manipulation becomes more than temporary?

Even if you were to strip all of the political undertones and economic commentary from the film, Kane still remains the best 2-hour lesson in filmmaking money can buy, Welles employing nearly every kind of visual technique into the film, from fade-outs to noir-lighting to time lapse to deep focus.

From a Hollywood genre standpoint, Kane transcends nearly all of them; it’s at once a mystery, a character study, a drama, a political thriller, a romance, a tragedy, etc. The only genre it seems to miss is Western, though if I were to watch it again I could probably make a case that Welles incorporate Western influences (I’m not going to, don’t worry).

And then there’s the making of the film, which is arguably just as remarkable as the film itself. (Sidenote: see RKO-281, an HBO movie about the making of Kane, starring Liev Schriber, Daniel Craig’s bad-ass brother in Defiance, as a young, ambitious Welles who in many ways echoes a young, reminescent Charles Foster Kane.)

Upon its theatrical release, Hearst banned any mention of Kane in any of his newspapers, and he owned a lot of newspapers. Welles would never direct a commercially successful film after Kane, most of his brilliant works relegated to cult classics (such as Touch of Evil and Macbeth) that are appreciated by film critics/aficionados and few others.

Orson Welles had the ambition to make a film that guaranteed career suicide, and in doing so provided future filmmakers with a template to work with, both from a narrative and visual standpoint (not forgetting that Welles revolutionized sound quality in “talkies”). However, Welles’ ambition didn’t make him wealthy like Kane. And if ambition doesn’t make you rich, what’s the point?