Old Stone (Lao Shi) is a film wrapped around the gut-wrenching dilemma of a man who knows a moral choice but struggles to find the fortitude to carry through with it against a broken social system punishing him for it. The divide between epistemological knowledge of right from wrong is often played in films, couched in a vacuity that assumes vagueness for insight into the moral condition of humanity, but Old Stone is content to build its foundation on a scenario with very little grey area. Instead, the film tackles a much more interesting conceit: the struggle to be righteous even when — especially when — we know with certainty what the cost will be.

Johnny Ma‘s debut film is both a potent exhibit of social realism, tackling a specific moral apathy in contemporary China and a tense, atmospheric crime thriller. A Chinese-Canadian film, it’s impressive as a first feature abundant with formal flourishes and an ambitious multi layered narrative, with an assured hand at the wheel and a commitment to a vision realized with far more clarity Ma’s experience would suggest.

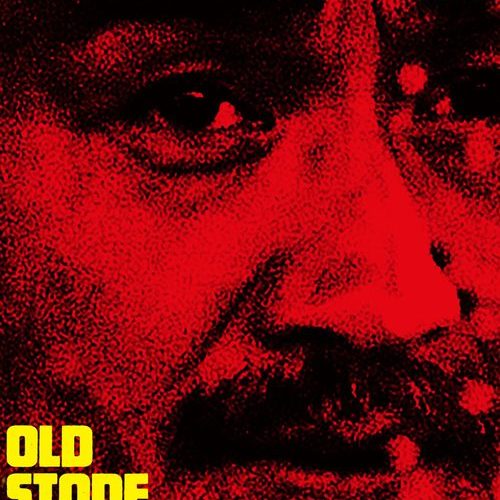

The film’s cold open, following a foreboding wall of red with the title card, is a verdant, ominous shot of thunder rolling through a forest. The static, foreboding shot cuts away to the story at hand, a flashback introduced in medias res: Lao Shi (Chen Gang), a taxi driver in a bustling Chinese city, struck a motorcyclist when a drunken passenger grabs his arm. Caught up in a flurry of passersby yelling out what he should do, but never offering a hand to help, Lao Shi gives up waiting for the ambulance and drives the comatose victim, Li Jiang (Zhang Zebin), to the hospital himself.

Thus begins the main narrative of the film, a foray into social realism within the recesses of human conscience, and the desire for self preservation, as Lao Shi realizes that although his actions may have saved the man’s life, he is now on the line for medical bills – which puts his family’s wellbeing at risk, doesn’t qualify for his company’s insurance, and is left assumed at fault by police. There are even strains of Clint Eastwood’s recent film Sully present, as Lao Shi sits before his insurance board, who insist he should have followed procedure, even if it would have cost the man’s life. Unlike Sully though, Old Stone presents a world without hero celebration, because to act righteously is to invite strife against one’s own life and family. Yet it’s still the same result: a nagging self doubt which seeps in through the cracks of the conscience and percolates under the surface of the psyche.

Time and time again, Lao Shi (whose Mandarin character means not only Old Stone, but also Honest) finds his righteousness met by aspersions and clucking disapproval from his family, neighbours, friends, and authority figures. His wife Mao Mao (Nai An) withdraws all of their money from his account without telling him in order to step his payments to the hospital, forces him to beg for help from a lawyer acquaintance, and considers him to be betraying his family.

Everyone can agree on two things, it would seem: it would have been better for everyone if the man had died at the scene of the accident, and Lao Shi should not have intervened. His own moral certainty slowly falters under the weight of the world pressing down against him, but even his morally compromised choices, like attempting to let Li Jiang die by taking off life support, are motivated not solely by self interest, but out of concern for others (in this case because Li’s wife told him that at least he has life insurance which could take care of them financially). The disintegration of his personal life and moral life slowly eroded from pure exhaustion at the lack of support, yet he manages to regain control before losing himself entirely. Morality may be defined at an individual level, but it is sustained on a social scale.

A moment when Lao Shi finally lets his rage manifest itself is reined in by a clever formal touch of editing. He sucker punches his boss (Wang Hongwei) who talked to convinced Lao’s wife to cut him off financially, and the score suddenly launches into a burst of rock and roll energy, before cutting a split second later to Lao’s daughter’s dance recital, which is diegetically set to that song. It’s a bold approach, mirroring his rage through the score, but instantly pulling back and repressing his anger, without sacrificing the kinetic frustration in the music, channeling it through the dance instead. Ma manages to maintain the film’s momentum without forcing sacrificing the emotional state of its Lao Shi in the process. The small moments such as these which are why Old Stone is such a notable debut.

If the film had merely continued along these lines, in the vein of the Dardennes crossed with Jia Zhangke, Old Stone would be been riveting. But Ma is not content to let it sit, opting instead to layer in another film beneath the surface – a jet-black crime thriller, shot through with noir elements and tinges of Black Coal, Thin Ice and Yellow Sea, which promises a bloody finale.

The two films within Old Stone bleed through each other through Ma’s ambitious structuring which places sequences out of order, but he does so for tonal purposes, controlling the atmosphere and fine tuning moments as needed, instead of crosscutting them as a puzzle to be put together. Throughout the film, he continually cuts back to the opening shot of leafy trees accompanied by thunder, and will often transition forward from the main story’s flashback to the present, where Lao Shi is shrouded in darkness and red neon, following a motorcycle through the dead of night. The tension of these moments, simmering under the surface of the main narrative, develop a palpable atmosphere of dread and a clouded suspicion about what Lao Shi is driven to do by his actions. Eventually the film gives way entirely to the thriller, and here the film begins to burst at the seams.

It’s a dense film for a runtime of 80 minutes, and the jolt in style and atmosphere is too jarring for its own good. While visually stunning (a cut between a lone red brake light of a motorcycle in the dark of night, and the red tip of Lao Shi’s cigarette as he follows in his taxi nears perfection), the story suffers for it. At its best when the film is constantly threatening to boil over, using its brief moments of noirish mystery to cast an air of tension humming over the rest of the film, the finale is a similar misstep to Dheepan, crossing genres in a way which slowly unravels the thematic resonance of previous half of the film.

The film culminates in a violent excess of sound and fury, ultimately signifying that nothing will change; honesty can be bent to its breaking point, and violence will only beget violence. It’s a hopeless, jagged final freeze frame, the individual crushed beneath the weight of the system.

Old Stone screened at the Vancouver International Film Festival and opens on November 30.