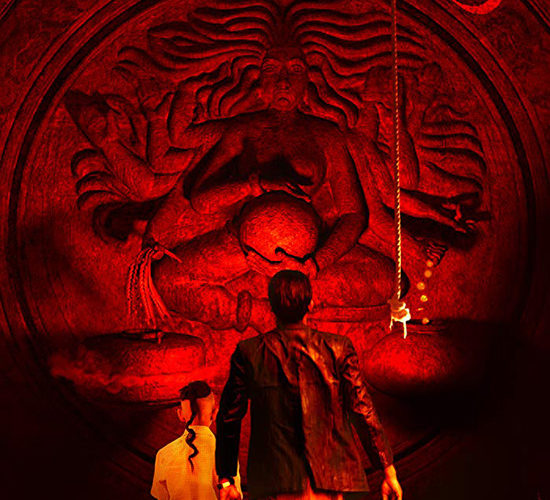

As the Hindu folktale at the start of Rahi Anil Barve and Adesh Prasad’s Tumbbad states: while the Goddess of Plenty birthed 160 million deities from her womb (Earth), the one she loved most is also the one that’s been erased from memory. His name is Hastar and he was her first. As such, he saw the wealth and food she provided mankind and coveted it for himself. He reached for the gold and his brothers and sisters allowed it for money was merely a vehicle for greed and unnecessary division. But when Hastar turned his sights on the wheat, they destroyed him before he could ever touch it. Unable to lose him forever, the Goddess of Plenty imprisoned him in her womb where he’s lived in shadows.

Nothing is ever truly expunged from history, however. Someone was bound to stumble upon Hastar’s name whether by divine fate or inspired imagination. In a world ravaged by selfish wants and desires, humanity needs something to worship with the ability to provide their ego cause and their target power. So with one gold coin came a promise of more. With one shiny trinket to dream on came a yearning to discover what else was lost and waiting to be found. That single piece of evidence is all you need to craft a story, the resulting hunger proof enough to spark interest passed on through generations. Its darkness leaves victims behind to warn new explorers of a danger they’ll simply ignore to find success where others tragically failed.

And once that name is remembered, it won’t be forgotten again. So we enter this tale through the eyes of a young bastard child named Vinayak (Dhundiraj Prabhakar Jogalekar). Screenwriters Barve, Prasad, creative director Anand Gandhi, and Mitesh Shah place this boy between the safety of a mother (Jyoti Malshe) that only wants the best for her children and the allure of infinite treasure believed to exist within Sarkar’s (Madhav Hari Joshi) — his illegitimate father — mansion walls. A legend that should die with this man is thus passed onto a child he never met, one tasked with helping to keep his own ancient mother alive. Cursed to sleep forever, her inexplicable awakening provides a chance to learn the truth. Does the gold exist and where?

Tumbbad continues through time as Vinayak reaches adulthood (Sohum Shah) still driven by rumors of wealth beyond his years. It also pushes through India’s history from British rule (the film begins in 1918) and independence. This progression can be seen as one of modernity — to leave the old ways in the past, Gods and all. Once again the continuation of Hastar’s existence on the tongues of man will rely upon an ancestral passing of information. And just like the horrors we saw in the prologue with a decrepit grandmother who’s more ghoul than human, any opportunity to prosper comes with a price. Whether it’s immortality or wealth, receiving anything from Hastar is a curse. He feeds on our sense of avarice knowing his gold will get him fed.

We watch as Vinayak transforms into his father by falling prey to power above life. And in the process we see his own son Pandurang (Mohd Samad) grow with the same desire as he did: money. There’s a cycle at work with mistresses (Ronjini Chakraborty), betrayal (Deepak Damle), and hubris. It doesn’t matter that Hastar is trapped within Earth’s womb because man will continue to travel there for just a taste of what he may have to offer. And while that sounds like a metaphor, the filmmakers here bring myth into reality. They utilize rules that bind supernatural entities such as demons to supply a false sense of security and create an elaborate well to Hell so Vinayak can test his luck and decide what truly matters most.

And if he fails, hopefully Pandurang won’t. But as the film progresses it becomes difficult to hope anything with Hastar’s claws dug deep into their flesh. They become willing to do anything for the gold they hold as birthright: even risking to sacrifice each other for the claim. This competitive nature to defeat the demon who supplies their wealth is intentionally cannibalistic, their jealousy a byproduct of its craven delights. The trio’s interactions together are grotesque with some fantastic set design and practical effects creating the Goddess of Plenty’s insides (and the deteriorating grandmother from the beginning) and computer work that give Hastar physical form. The production’s budget and collaborators are rare for genre work in India, so Tumbbad‘s success could go a long way towards changing that.

It should too if it finds the right distributor. The religious aspects are entrenched in Hinduism with distinctly Indian environments and history impacting its characters’ recklessness, but that’s all part of the appeal because it renders this horror thriller unique. Like Turkey’s Baskin or Indonesia’s Satan’s Slaves remake, Barve and Prasad are able to inject their distinctive culture with routine tropes that lend a visceral familiarity to folklore completely foreign to international audiences. It allows its new terrors and monsters the potential to be seen as more than knock-offs of fan favorites with singular worlds dictated by rules unbeholden to Christian scripture’s limited scope. As long as mankind’s universal concepts of greed, vanity, and fear remain as motivating factors for its “heroes,” we’ll relate and absorb the unknown.

Tumbbad opened the Venice Film Festival’s Critics Week.