A family’s brutal murder is the catalyst for this hackneyed treatise on victims and perpetrators in this slow-burning, rudderless South African entry in competition at Venice. Oliver Hermanus’ The Endless River film garnered boos and even a shout of “pathetico!” at the end of its press screening on the Lido – that might be harsh, but at times it really does feel endless.

We open in the Western Cape town of Riviersonderend after the release of small-time gangster Percy (Clayton Evertson). His wife, Tiny (Crystal-Donna Roberts) hopes to restart their relationship away from the world of crime and gang violence that has cracked South Africa’s post-apartheid social landscape. Her wish will go unfulfilled.

Living nearby is Gilles (Nicholas Duvauchelle), a Frenchman relocated to South Africa, whose home life stutters. He barely speaks to his wife at dinner one night, leaving the house in a huff, returning later to discover his wife and children murdered in an execution-style killing. His grief is laden with guilt at having been absent, distraught further by the fact that local cops say they’ve got no leads to investigate. Seeing how Gilles is struggling, the town’s police chief Groeneweld (Darren Kelfkens) hands Gilles the picture of someone (Percy) he suspects might be involved as a gang “re-initiation” after prison.

This is a strange, curious picture that’s tonally unsure of itself, flitting from naval-gazing sequences when our protagonist ponders into the distance and extreme violence – such as the slo-mo sequence involving Gilles’ wife’s rape and murder. The latter scene had an exploitative edge that rankles, not to mention a tad insincere view of the black African’s social condition that pervades the film. “I want them dead,” Gilles screams of the attackers to Groeneweld. “Isn’t that what you do in Africa?”

Indeed, the film’s tonal inconsistency starts as early as the opening credits, which seem to hark back to 1950s western tropes with large font italics and luscious scenery. The landscapes, photographed majestically by Chris Lotz, don’t look far different from the American outback, and yet if Hermanus aimed at some post-modern irony it’s lost here. The film resembles more a noir-ish drama than any sort of revisionist western, and Braam du Toit’s orchestral score is naff as it seeks to overpower the senses.

Hermanus’ script is most powerful when presenting the terror of knowing crimes go unpunished. Indeed, after the events, Hermanus shows that even when Gilles and Tiny – the two characters who anchor the story – laugh and smile, they’ll never be happy again.

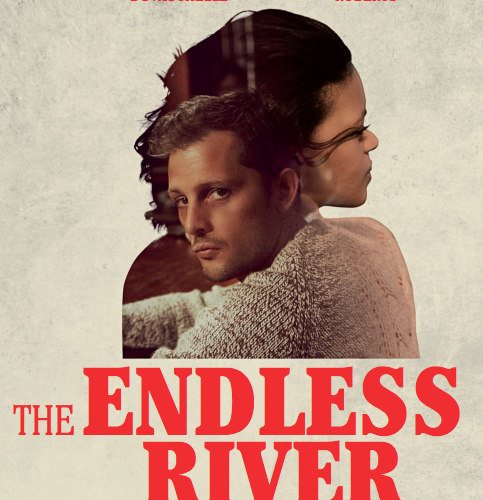

But his direction lacks tension or drive, dwindling further as the two protagonists’ lives intermingle further and further. Duvauchelle is confined by a character that leaves little room to develop beyond wild shouts and a rather clichéd descent into alcoholism. At least Roberts has more to do after her own personal tragedy. Her Tiny carries a mysterious fragility, and she’s able to say more within her silences than Duvauchelle does with a hysterical rant.

Hermanus strives for enigmatic characters and ideas to do with victims and criminals, but he hacks the ending that closes the book on what would have been some intelligent psychological ideas, rendering The Endless River a shame.

The Endless River premiered at the Venice Film Festival.