Whatever new could be said about Paul Schrader as an artist—curving around the extra-textual value in Kickstarter campaigns, Facebook posts, and tragic losses of final cut—is almost entirely on the back of First Reformed. A cultural smash first propelled by surprise of the he’s-still-got-it! variety that, as those things always do, faded, now denotes career reset—a generational shift for telling us his anxiety-ridden men of ‘70s and ‘80s landmarks stuck around to become the doom-scrolling generation whose problems are more global than personal. (Though obviously that too.) The catch of this conquest is a greedy fan (hello) alternately thrilled at the existence of another film and worried a final statement for the ages is rendered naught. A broken promise? Please; he owes us nothing. But Ernst Toller’s martyrdom is hard to sacrifice as a last note.

My fear of folly dissipated before The Card Counter‘s first shot. Martin Scorsese’s name looms large from outside, all bold colors and larger-than-the-auteur typeface on Focus Features’ poster; that’s a misdirection. His role, already ambiguous to the practical realities of production, loses its oomph in the opening credits boasting… well, I literally did not have time to count the eye-crossing number of executive producers needed to shepherd Schrader’s vision onscreen. I could only assume we’re not playing it easy.

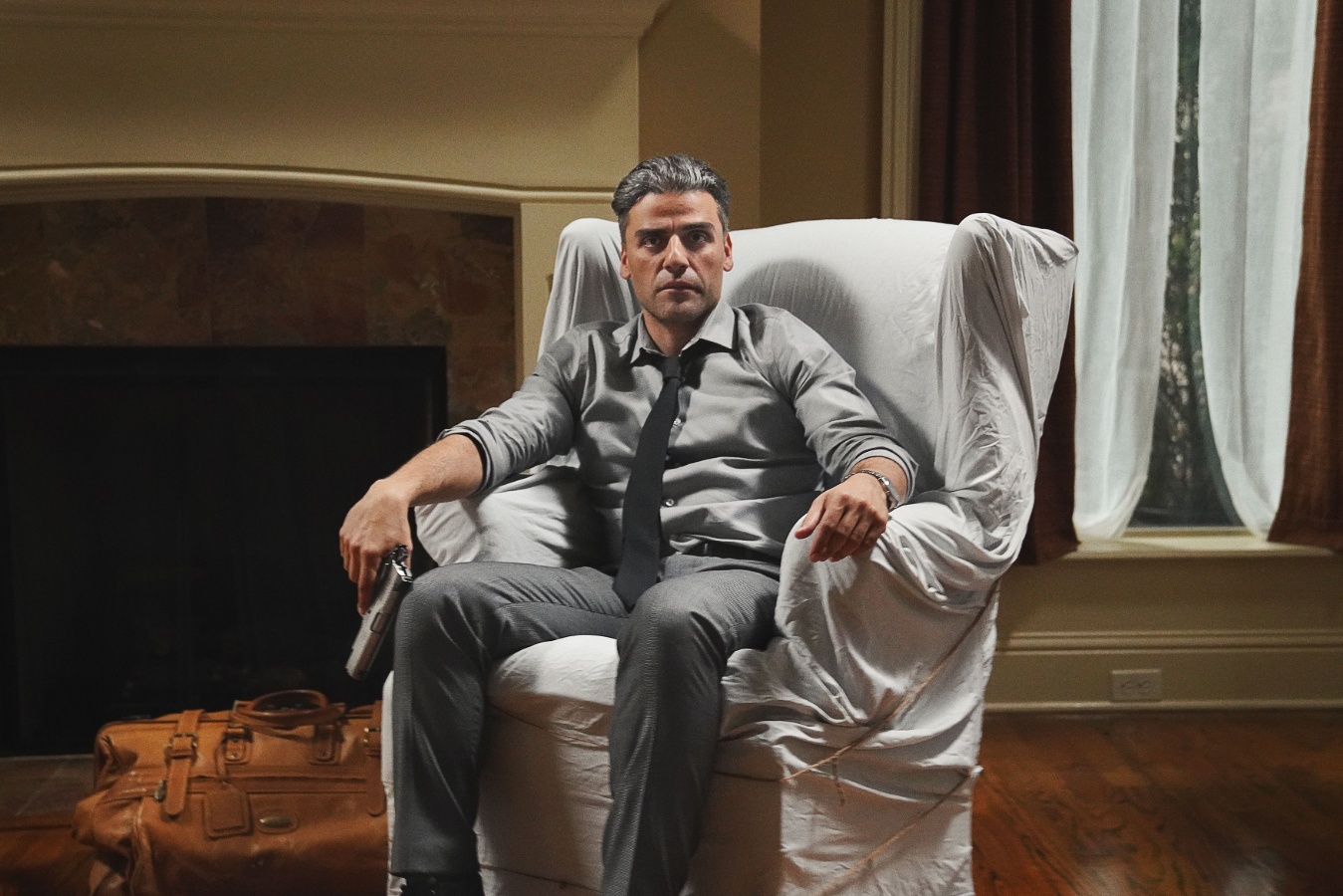

Not that the bits are unfamiliar. William Tell, Card’s protagonist, is the latest configuration of Schrader’s brooding, an edge-of-catastrophe man in a room—you know what from 1976, American Gigolo, Light Sleeper, The Walker, First Reformed. Familiar bits, but pieces that sing. Hunched over a table, scrawling in a notebook, lying in repose, personal philosophy conveyed in tones that suggest he’s had time to think through this manifesto plenty, Tell spins a story among the most narrowly focused and first-person Schrader has ever staged—narrative details filled expressly when our hero can acquire them and, inasmuch as they matter, could be resolved beyond his notice. And per this movie’s mood-piece priorities, often are.

This is Schrader in a proper groove, playing the hits as his eyes and ears manifest some new formalist phase. From an admirer’s stance that combination could hardly be more welcome or validating. Having practiced screenwriting years before stepping behind a camera and, credit-wise, never quite letting one prioritize another, there has sometimes been the sense his formalist cachet, however commendable, is collaborative—a visual practice I’d call necessary before expressive, evocative once it can escape prescriptive. While nine times out of ten would make it foolish to call two films separated by four years a pattern, 40-plus years of directing are evidence enough to pinpoint late-late style, the return of DP Alexander Dynan and editor Benjamin Rodriguez Jr. converging this film’s bloodless images and hear-the-creaking-floorboards sound with memories of First Reformed sans suspicion of repetition.

If the emotional matrix is largely unbending—bad, slightly worse, or slightly less bad—environments fare little better; it sure plays like a canny joke that the industrial prison in which we meet Tell has a nearly note-for-note color palette with his motels of choice. (This point could’ve been underlined further and it’s times like these you understand what constitutes restraint.) It’s doubtful Schrader feels warmer to the casinos and their denizens, though they’re more source of fascination, of formal investigation, than disgust or disregard: a brief-ish tracking shot over the floor—which might offer more camera movement and foley sound than the entirety of First Reformed—is immersive without getting too close or familiar.

At this moment Schrader’s fashioning performance style into a science: brooding but not brick-walled, sharp and witty on an even keel with the perpetually dour room tone. It’s hardly a moment before Oscar Isaac, after so much time in the fantasy / sci-fi realm showing himself a real actor, takes the mantle from De Niro, Gere, Dafoe, Harrelson, and Hawke. He sure looks it: always clean-shaven, sometimes on the verge of a smile, distinct in pieces—a hard forehead, a strong jaw, attentive eyes—with which his voiceover finds counterpart (and with which it is sometimes the counterpoint), his face is Schrader and Dynan’s landscape to express intelligence and rage. As Tye Sheridan smartly plays slightly dumb, part and parcel with the weird beefiness of so many American men his age, Tiffany Haddish sublimates her comedic crackliness for Card Counter’s smartest player. (If you’ve got to endure a ruthless world, quips and smiles will do the job.) Both suggest total synthesis—of characterization, performance, and personality, most importantly such tenets of this hushed milieu; something far, far harder to achieve than any intended result could imply.

Willem Dafoe hangs over The Card Counter as the shark in Jaws. Introduced offscreen via voice that could belong to literally nobody else on earth, he only appears with careful attention to accessories that accentuate his otherworldliness—indoors some ostentatious sunglasses, in flashback an army commander’s uniform his (so phonetically repellent) Major John Gordo wields to enact unhindered evil. A marvelous presence, of course. Yet were we to identify one questionable angle of an otherwise precise picture it’s the separate-but-equal revenge tale into which he factors.

I suspect our filmmaker’s interest is most compelled here. Case in point that Dafoe’s appearances pair hand-in-hand with Card‘s biggest formal gambits—one jaw-dropping, the most stunning depiction of a particular chapter in modern American history I’ve ever seen. But it’s hard to comprehend as a parallel track. Perhaps purposely, though at nearly every turn I found myself asking how different narrative directions would, could, should align, notwithstanding its emphasis on the desperation and need for necessity plaguing characters’ lives. Whatever Schrader’s enthusiasm for the game, here intentionally deflated of dramatic effect, I do wish that congealed with Dafoe’s angle more neatly. Not the set pieces or big narrative blocks a title like The Card Counter suggests, gambling is an interstitial moving us to the next drink or floor walk or hotel convo—good enough, not per se something that hinders the organic flow of the experience.

With two weeks’ hindsight, The Card Counter’s powers linger well past plot machination—its methods of approaching incident miles deeper than how they’ll play, its pauses in conversation bruising harder than anything spewed. I’m smitten with his latter-day tone-setter vibe, the stumbles amusing (I’m curious who got that horrific music into key scenes) and indulgences almost touching; Schrader (yet again) stages Pickpocket’s final moments, now in a form so distended it’s first comic, then admirable in lack of compromise. When I met Schrader in 2018 he quoted to me, on the subject of his new phase, a Ride the High Country line about entering one’s house justified. The Card Counter suggests, persuasively, no reason to leave.

The Card Counter premiered at the Venice Film Festival and will open on September 10.