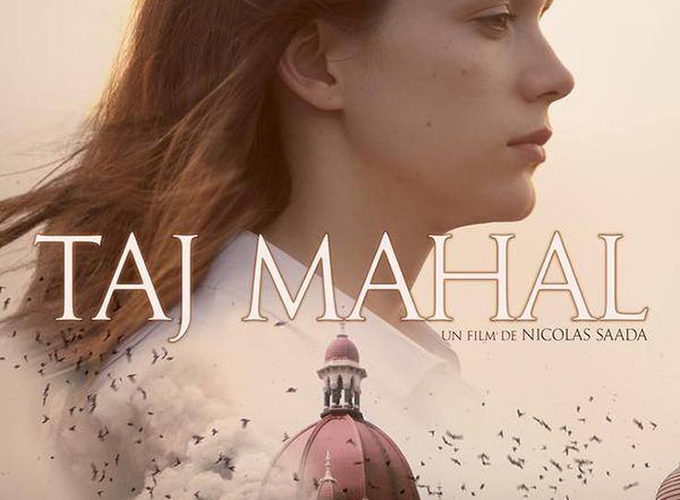

The attacks of November 2008 in Mumbai that left 195 people dead become a claustrophobic, almost austere affair in the hit-and-miss Taj Mahal, starring Nymphomaniac’s Stacy Martin. She plays 18-year-old Louise, a newbie in India after her father (Louis-Do de Lencquesaing) relocates there for work, staying in the five-star Taj Mahal Hotel on the city’s seafront while waiting on a new house. Her company is all we have for most of the film, as we join her knuckling-down after locking herself in her room, trying to outlast the siege while bombs and bullets ring around her.

Critic-turned director Nicolas Saada’s film is best in these tight, claustrophobic moments. But we begin as Louise, on the cusp of adulthood, wanders the streets of Mumbai with her French father and her British mum (Gina McKee), a relationship that mirrors Martin’s own parentage. She switches between French and English throughout (believably, it must be said), representing perhaps Louise still identifying whom she is as a person, although Martin’s vacant, snow-white expression might be misinterpreted for dispassionate boredom.

However, Louise has to grow up fast. As her parents leave for a restaurant meal, Louise behind in their plush hotel suite. Interrupted while watching Hiroshima Mon Amour on her laptop – a film in which one heroine’s suffering reflects an entire city – she hears banging, notices the streets are deserted, and the noises escalates.

Louise’s point of reference for much of the next hour of the film is her mobile phone, a link with her parents that’s how she understand what’s happening around. She locks the doors, turns off the lights and hides in the bathroom, with our only grasp of the events coming from blasts and noises, effectively created by Erwan Kerzanet’s dynamic sound design.

But while technical elements, including Leo Hinstin’s parred-down cinematography, are astute, it’s in the thinly-written characters that Taj Mahal sags. Louise’s experience is based a survivor of the attacks, but it’s hard to believe in Martin’s deadpan impression of someone under psychological strain. Phoning a colleague of her father who is trapped in the hotel basement, her reaction to his report that terrorists are “shooting everything” is more or less minor disappointment.

Saada’s script is perfunctory rather than revealing anything significant about the attacks, or indeed what it’s like to be in the center of a maelstrom like this. The original idea is sound – most films about terrorist attacks are more gung-ho and larger in scope – but by centering on a privileged, white westerner, it’s hard to gauge what’s revelatory about this particular story. A porter who ordered Louise back to her room gets the only eulogy as his picture is viewed on the wall of the dead.

The ten Lashkar-e-Taiba militants laid siege to Mumbai and its cosmopolitan population, and Saada’s focus on Louise – and later another rich European in a cameo from Alba Rorwacher – seems curiously dismissive of the wider issues at the heart of India’s struggles with extremism.

Taj Mahal premiered at the Venice Film Festival.