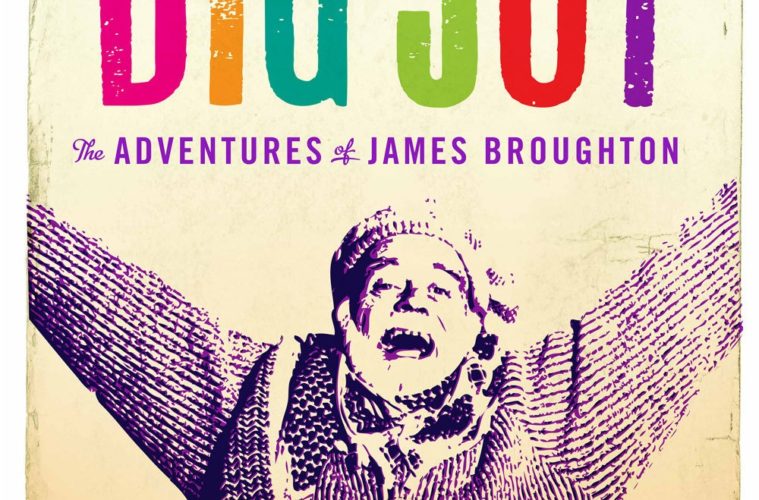

The Tribeca Film Festival continues its legacy of programming work about experimental film with Big Joy: The Adventures of James Broughton, an insightful documentary about the liberation, career and evolution of the prominent San Francisco-based experimental filmmaker. His story is perhaps less known than that of Stan Brakhage, Maya Deren, Michael Snow, or Jonas Mekas (at least in my East-Coast-based film education).

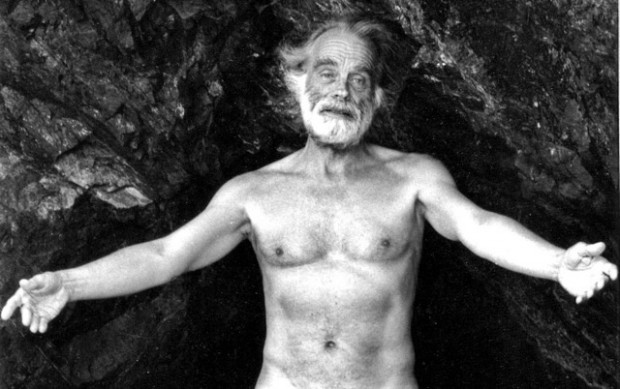

Big Joy we later learn is an apt nick-name for everything Broughton would embrace, that is until he stumbles back in the closet and gets married at the suggestion of a collaborator, Brakhage. Wasting away in the suburbs following The Bed (a heterosexual romp) he later finds its liberation with a man 30-years his junior, filmmaker Joel Singer. It is this later period, once Broughton again “comes out” following a slow period of creativity, that his work returns to “joy.”

Broughton’s films make sexuality light and bouncy, a sunkissed west coast sensibility verses the gritty queer films made in New York (or the coded queer films in LA, hiding behind such notions as the “confirmed bachelor”). Jack Foley calls Broughton “a myth maker” and this documentary isn’t a skeleton key to Broughton’s work, however there are limits to the access filmmakers Stephen Silha and Eric Slade have, including two of Broughton’s daughters who refused on camera interviews (his son admits his dad was never around).

The story is largely told by those that loved him, including former partner Pauline Kael (in archival footage), and those who worked with him, including George Kuchar, his former colleague at the Art Institute. The film blends archival materials and talking heads effectively creating an excellent intro into his life and work. The role of experimental filmmaking is to bring to the surface ideas that narrative filmmaking cannot, often blurring the meaning in image, it can unlock subconscious or formal ideas through representation (or lack of representation). However Brouhton’s work was never quite this serious. The filmmakers employ an “explainer” to fill in some of the gaps, an actual guy with a dry erase board filling in the history of Post-War San Francisco, a frontier town. Broughton’s work comes just years before the emergence of the beat generation and will last until, as Joel Singer recalls, he slowed down at the age 75.

Big Joy is an enlightening documentary, a celebration of the joy and the pain, with the latter often making the former that much sweeter.