A film about an infection and the upset, paranoia, and unease that follows is, well, tailor-made for right now. There is no better time, then, to see director Jin Wang’s The Best Is Yet to Come, a selection at both the 2020 Venice Film Festival and the Toronto International Film Festival. It is a complex study of the illegal blood trade that helped hepatitis B carriers circumvent the discrimination they faced when seeking jobs and applying for school in early-2000s Beijing. While there is not a direct correlation to the COVID-19 pandemic, it is impossible not to make connections between both the story itself and even its creation. As Wang explains in the film’s press notes, “Due to the pandemic, post-production took place online. The editor and I were 1300km apart. Distance sparks reflection.”

The Best Is Yet to Come is the feature directorial debut from Wang, who has served as assistant director on a number of Jia Zhang-ke masterpieces, including A Touch of Sin, Mountains May Depart, and Ash is Purest White; the filmmaker serves as a producer on Best. While the film shares Jia’s focus on social injustice and high-level corruption, it never reaches the same heights. It is a compelling drama––one based on a true story––and an important one, to be sure. But there are numerous missteps that lessen the impact and slow down the dramatic energy. While this keeps The Best Is Yet to Come from greatness, the film remains a powerful, worthy tale of investigative writing and compassionate reportage.

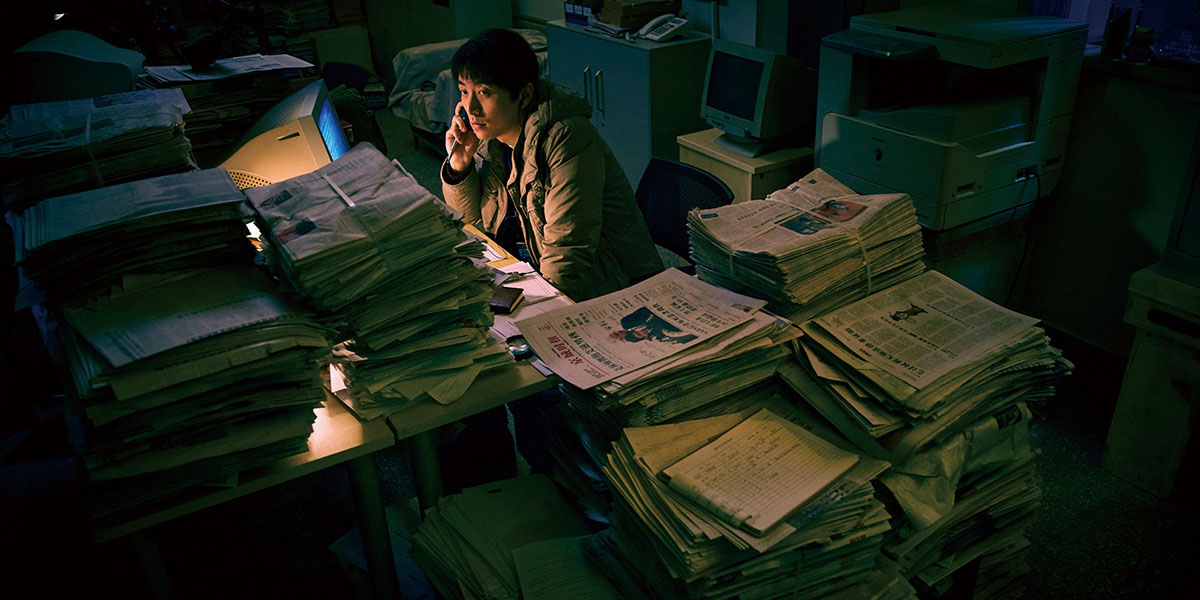

The setting is post-SARS China, 2003, a world in which the reach of the internet was growing but print journalism was still undisputed. One of the many twentysomethings seeking his place in this mammoth, densely populated city is Han Dong (Bai-Ke), a wannabe writer without a college or even high school degree. What he has, however, is the ability to observe: “Reportage isn’t about having a diploma,” he says. “It’s about keen observation.” His desire to be a reporter is what brought him to Beijing. Luckily, he soon lands a coveted spot as an intern for the Jingcheng Daily newspaper. (During his first visit to the bustling newsroom, he is described, in casually devastating fashion, as “a reader.”)

He and his fellow interns are given a crash course in the reporting aesthetic in a rather cliched but nicely edited sequence of rapid-fire wisdom: “You’ll be a reporter when you’ve worn out five pairs of shoes.” “Most news stories live for only one day.” “The pen you hold is your power.” “A news story can help people. But it can also crush them.” “Your breakthroughs, your mistakes, will all be magnified.”

A star reporter, Huang Jiang (Zhang Songwen), is a newsroom force of nature and takes Han under his wing. After an early success working together to report on a mining disaster, Han finds a story of his own. It’s a tangled, complex situation in which hepatitis B carriers hire stand-ins for blood tests, or have their results changed by a doctor. He goes undercover in this mysterious operation, and prepares what will be a front-page story. However, his discovery that a good friend is one of the carriers paying for faked results. Han learns that even though these actions are illegal, they are necessary. Hepatitis B carriers are legally discriminated against, and treated with disdain in society.

Han’s moral dilemma––kill the story, or let it run–segues into a new concept, an attempt at sharing the stories of carriers like his friend. Unfortunately, once Han leaves the newsroom, interest lags. The loss of the dynamic Huang as a character is a key reason. And while Han’s quest to make the public aware of the devastation being caused against more than 100 million carriers is powerful, the manner in which it is told is predictable and often maudlin. Han himself is a rather emotionless character. This is by design, and that often leads to subtle comedy. But that lack of passion also makes it difficult for the audience to invest in Han. It is easy to invest in those he is seeking to help––video sequences of these folks are devastating––but not so much in Han himself. The character of his girlfriend does not help; the role is underdeveloped and nearly invisible.

These are a few of the film’s failures, and they make an impact. Despite these, however, The Best Is Yet to Come is without question worth viewing. For many audience members, this era of modern Chinese history is not well known and the parallels to COVID are clear. A bolder script, however, may have helped push the film into a more memorable realm. There are two specific breaks from reality––one about midway through the film, another at the very end––and they are welcome, if a tad poorly conceived. These sequences display an ambition from the first-time director to bring freshness to a standard story of investigative reporting. Perhaps his next outing will see him push that freshness even further, and create an even better film.

The Best Is Yet to Come premiered at Venice Film Festival and is screening at the Toronto International Film festival