The story of AFL superstar and Australian of the Year-recipient Adam Goodes should resonate for Americans who’ve been following the crusade of former NFL quarterback Colin Kaepernick. From his minority background, stalwart fight against injustice, and the resulting sports-wide fan backlash—their similarities are endless. The people loved Goodes because he left everything on the field and checked every “gladiator” box as far as playing through debilitating injuries to carry a team on his back towards a championship. They loved him so much that they initially let him have a soapbox to speak-up for the aboriginal community of which he’s a member. This was his incentive to score. Bleed for us first and then champion the unfortunate. But you better not dare place their ills at our feet.

That’s the rub, right? My family is Middle Eastern and yet even they fall prey to the white trappings of seeing marginalized people as performers not allowed to complain. They’ll hire POC and LGBT employees to work under them while patting themselves on the back despite holding onto the thinnest thread of Catholic superiority when debating why the former are ungrateful and the latter a disgrace to the sanctity of marriage. That’s what happens when you sniff the realm of the ruling class—when you don’t believe those above you on this socio-political spectrum are saying the same about your people behind your back. So when an athlete stands up (or kneels) for something that reminds their oppressors of that oppression, no amount of trophies will matter anymore.

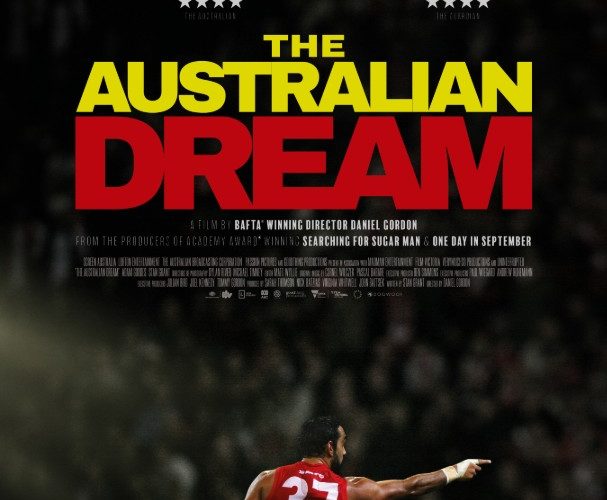

Director Daniel Gordon’s documentary is entitled The Australian Dream because of something television journalist (and aboriginal descendant) Stan Grant wrote in the aftermath of Australian Rules Football stadiums booing Adam Goodes to the point of retirement. It has to do with the duality of their nation and the white celebration of Australia Day in the face of the Black citizens that call the date Invasion Day instead. It’s about the fact that British colonizers landed upon this continent and declared it “empty” and thus theirs to take. From genocide to eugenics to casual racism, this dream of harmony and righteousness has always been a lie. Confront the white majority with this fact, however, and they will adopt a common defensive posture of hiding beneath humor, misunderstanding, and ignorance.

This is as much a history lesson for white Australians as it is a biography for Goodes because we learn about important things like the so-called “stolen generation” of aboriginal children taken from their families to be assimilated into the colonizers’ culture. We also learn that these indigenous people are the longest, continual inhabitants of any land on Earth at over sixty thousand years. Think about that. Sixty thousand years before Britain arrived and stole everything from them for the past two hundred. Yet when Adam Goodes dares use the platform of Australian of the Year—given to him by mostly white Australians—to ask for the start of a conversation around this disparity of rights and opportunities, his idolaters become his detractors. They tell him to grow-up.

This is their excuse. It’s what they’ve been waiting for because they knew they couldn’t get away with booing skin color. Now they can boo politics. Guess what, though? Skin color is political. When ten people start a derogatory chant and the other one hundred people in that crowd join them, the line between their hate and your “fun” is erased. As soon as a target of abuse tells you you’re being abusive, a refusal to stop becomes your acceptance of that abuser label. You can either learn from a marginalized person telling you you’re being racist or you can prove it. Their job isn’t to deal with your bigotry. It’s to point it out and see if you really are, as you say, “Better than that.”

Gordon gets a bunch of well-known figures in Australia to speak on the subject. There’s Nicky Winmar and his famous magazine cover pointing to his skin with pride. There’s Adam’s brother, coaches, and teammates as well. And right along with them is political commentator Andrew Bolt who probably thinks he’s giving the movie an objective dissenting view that people need to recognize the context of what Goodes “became” after turning his focus away from sports and towards social justice. That’s not what’s happening, though. Hearing this blowhard “defend the children” and call people “babies” against the nuanced reality of what’s going on only reveals how explicitly racist his implicit racism has become. Bolt believes the burden of peace should be put upon the victims rather than their victimizers.

That’s how so many people think and why it’s necessary to call out abusers regardless of age, race, or gender. When a thirteen-year-old girl calling Goodes an “ape” becomes a story about that girl’s life being ruined because the world now knows she’s a monster, the bias can no longer be ignored. When the nation turns to Adam and vilifies him because he should know better than to accuse a child of something they can’t understand (he in fact does the opposite of this) rather than the systemic racism that allows her and her community to dismiss what she said as a joke, something has to change. What makes Goodes such an inspirational hero is the fact that he never matches hate for hate. He’s teaching tolerance.

It’s a lesson that sadly won’t be absorbed by those who desperately need it most. I do think, however, that Gordon and Grant (who’s credited as screenwriter) do a great job putting truth up on-screen so those who can be swayed will. It helps too that viewers can’t be bullied into somehow using Goodes’ athletic prowess against him. Where many dismiss Kaepernick sight unseen because he “never won anything,” that straw man argument holds no weight with two Brownlow Medals and two AFL Premierships to Adam’s name. The abrupt shift from adulation to heckling is therefore very specifically rooted in race and this film ensures there’s no room for anyone to deny it. Except for the racists of course. It’s high time we start calling them all out.

The Australian Dream premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival.