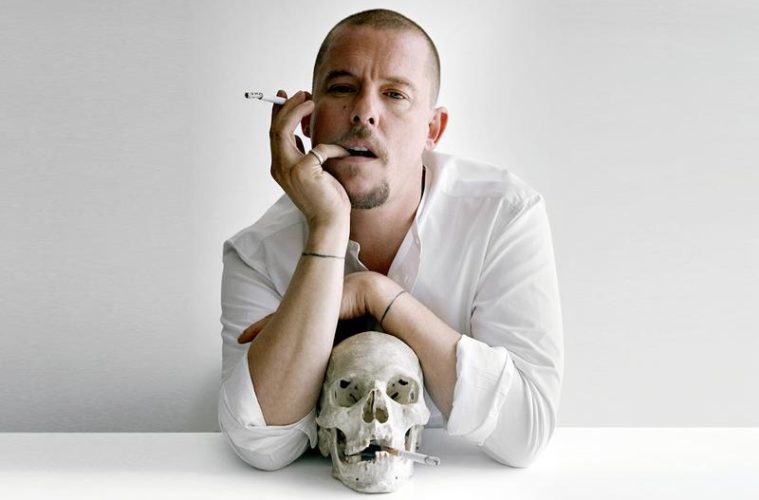

In their documentary McQueen, directors Ian Bonhôte and Peter Ettedgui craft a lovely portrait of idiosyncratic fashion designer Alexander McQueen. Through archival footage, interviews with friends and collaborators, and elegant filmmaking techniques, the filmmakers in many ways evoke the emotions provoked by McQueen’s art. The film is filled with moments where violence and beauty become partners in a sensuous dance, and they study the late designer’s ascent within the English class system in a manner that would make Ken Loach proud. At the center of McQueen’s work was a constant battle between life and death, and in the documentary we learn about the pivotal moments in the designer’s life that might have inspired most of his work, but rather than going for facile psychological interpretations, the filmmakers let the art speak for itself, directly to us.

We spoke with self-proclaimed, fashion non-connoisseurs Bonhôte and Ettedgui about what attracted them to McQueen’s story, their relationship to nonfiction filmmaking, and Michael Nyman’s breathtaking music.

The Film Stage: Do you remember when you first became aware of Alexander McQueen?

Ian Bonhôte: I moved to the UK in September 1997 and by October he had taken over Givenchy, so he appeared everywhere in the news. So I became aware of him as my own creative career got started in my late teens, early 20s.

Peter Ettedgui: For me it was around 1994 or 1995 when McQueen was starting to get headlines about the bumsters and the shopping shows and all that. He was a very controversial figure in the press. My father, who was a fashion designer and retailer in London, worked with him for a bit and knew him and he told me “this guy is a genius.” He told me how Lee [Alexander McQueen] was a very talented tailor who came from nowhere from the East End, made an apprentice on Savile Row. Even though back then I didn’t think of making a film about him, I was very intrigued.

Lee was always in the tabloids and we all have a media-made idea of who he was. What was the biggest challenge for you as filmmakers when trying to show a different side of him in your documentary?

Ian Bonhôte: Our challenge was to ignore all that sensationalistic side of him and go back to refocus on his work. Lee said, “If you want to know me look at my work,” so we took him to his word. That was our main interest, we wanted to go behind the person, behind the genius in a respectful way. We felt that him taking his life still is very new in a lot of people’s minds, so we knew if there was any other direction we took we would alienate people and they wouldn’t collaborate with us. So we wanted to put the work at the center.

Peter Ettedgui: I would only add that to some extent the portrait that you make is conditioned by the interviews, archive and what that gives you. What we found when we interviewed people is that there was this extraordinary well of love for him. When we looked at the archives we saw him having fun, with this ebullient character, with his dogs, with his parents. We knew there was another Lee beyond the one presented by all of the controversial press.

During the studio era women were editors because studio heads thought they were like seamstresses who were great at sewing film together. In many ways I believe fashion is the art form that most resembles filmmaking: you have this visionary who recruits a team to make it come to life. Did you find any parallels between fashion and filmmaking while making McQueen?

Ian Bonhôte: I really like this question. I agree with you, there’s a conductor, a director at the center. Making the film we came up with the metaphor of Lee being the tip of a spear and right behind him were all the collaborators including the people in the atelier who helped push that single vision forward. Lee was a great talent spotter. He also combined lots of influences and I agree his work was like that of a director. As a director you take inspiration from music, photography, a show, another movie, nature, movement, dance… I get inspired by choreography all the time. The way we approached the documentary was not as journalists but as filmmakers. We wanted to put emotion over information. We wanted to create an emotionally involving experience.

Peter Ettedgui: We looked very carefully at Lee’s work and what we really responded to was the juxtaposition of classical structures with rule breaking details. We wanted to bring that approach into the film, a classical five-act structure, with a spirit of improvisation found by stitching together very violently different kinds of archival material: home movies, photography. We thought we could make the sequences iconoclastic and great fun, within this structure. I love your analogy of film and fashion.

You mentioned Lee used to say he was in his work, can we say the same about your work? If people look at McQueen can they see Ian and Peter?

Peter Ettedgui: I think it does because inevitably you gravitate towards the subject because it speaks to you. In the case of Lee’s story we were moved quite profoundly, but there were things within it that we responded to. For example, the way he scraped his way to the top of the industry and broke all the rules. Also the spirit of him being the tip of the spear but this group of friends all coming together like a movement and taking Paris by storm together. That’s not something we’ve done but something we dream of doing, establishing yourself on that kind of stage with a group of close friends who are genius collaborators. It also spoke to us because it’s such an emotionally profound story and we’re both emotional filmmakers. We want audiences in the cinema to go on a bit of a rollercoaster ride. We’re attracted to stories where you’re laughing one minute and welling up the next. That’s the kind of stories we want when we’re in an audience, and with McQueen we thought we could express that side of ourselves.

Ian Bonhôte: Our collaboration happened naturally too. We didn’t set out to make the film together. So that similar strong sense of emotions brought us together and whatever decision we had to make we always put the audience first. When you make films they can be an extension of yourself, but they also have to respect who you’re working for in a way. We don’t want to tell stories that are just us. We want to reach out, break out and touch people.

Lee himself said that he wanted people to be exhilarated or repulsed by his collections. As an audience member there’s nothing worse than films that just make you go “eh.”

Peter Ettedgui: In a sense this was a film we weren’t supposed to make. Lee broke all the rules and our experience was uncannily similar in that nobody in the fashion world wanted us to make this film.

Ian Bonhôte: We were not granted permission by fashion insiders. There’s a sense if you do something about a fashion designer you need to be knowledgeable of fashion. We thought it was better we didn’t know anything, so we saw Lee as a man first, very much like an audience who didn’t know about fashion.

Peter Ettedgui: We had to be guerrilla filmmakers and use our charm and begging abilities to have access to archives, to convince people to come on board and do interviews, and we had to do it very quickly because those people were prohibited from being part of our journey.

In terms of the cinematic elements of Lee’s work, I knew he liked Michael Nyman’s music but I never imagined I’d get to see his collections set to Nyman’s scores. The way you use “Fish Beach” with McQueen’s “La Dame Bleue” collection was probably the saddest any movie has made me this year.

Peter Ettedgui: Well, thank you–that was our intention. There’s also one piece of music Michael composed for a Lee show that Lee never actually used. When we first met Michael he played it for us and we used it three times in our film. It’s called “Lee’s Sarabande” and we were so moved by it we knew we needed to have it in the film. Lee’s music choices for his shows were great, but they don’t work in a movie. Some of the music has been dated a little bit, but as soon as we started experimenting with Michael’s music the material came to life. Even if the archival footage wasn’t great, as soon as you paired it with Michael’s music it felt like a movie.

Ian Bonhôte: Sometimes due to budget restrictions filmmakers forget how important music is to the process. What I love with Nyman is that many people might recognize the tracks but they don’t know where they know them from, so they’re comforting but also throw people out of their comfort zones. When people find out every single track in the film is by Michael Nyman they’re surprised. At one point we tried getting a Sinead O’Connor song, but they made it quite difficult for us, but the minute we tried that scene with Michael’s music we asked ourselves why did we even bother with Sinead?

Peter Ettedgui: I think Michael was absolutely thrilled with how we used his music. He was a fantastic collaborator. Even though it was all pre-existing material he made suggestions, criticisms and as he said himself, “The final film is as much a portrait of Michael Nyman as it is of Lee McQueen.”

Annabelle Neilson, another of Lee’s muses, passed away the week the movie opened in the States. She’s not really in your film much, but I wonder if you have any insight on what their relationship was like?

Ian Bonhôte: They had a very strong relationship, she was a very important part of his life. She’s also in the film more than you can imagine. The Fairlight section was actually filmed by Annabelle’s then boyfriend, she spoke to us about Lee and granted us permission to use the footage. We had some conversations with her while we were making the film, but she never felt comfortable enough to sit down for an interview. She said the emotions were too raw. She was supportive of the film without taking part. We were sad to hear news of her passing. We hope she rests in peace.

Peter Ettedgui: I’m sure she’s up there with Lee. She was actually introduced to him by Isabella Blow, and a big element of the story is her friendship with Lee. Perhaps it would’ve been difficult for us to also incorporate his friendship with Annabelle. We wouldn’t have been able to make it full justice. We would’ve needed another film just about their relationship. Her presence is in the film. She gave us her blessing and that was very important to us.

Peter, when I realized you co-wrote Listen to Me Marlon, I thought it made perfect sense that you directed McQueen. They both challenge what nonfiction films look like. What are some tropes of documentaries that you wish would disappear altogether?

Peter Ettedgui: In a sense Ian and I are the same. This is his first documentary and I’ve come to the form recently. Five years ago we probably would have said we’re not interested in making documentaries.

Ian Bonhôte: I would’ve said that a year and a half ago.

Peter Ettedgui: I suppose the association people make is of a bunch of people sitting in a chair talking to a camera, or historical reconstructions, it’s kind of putting information over emotion in storytelling.

Ian Bonhôte: There’s a lot of documentaries that go for the journalistic side, while I tend to really fall in love with people. All the people in our documentary shared these experiences with Lee, so even though he’s our protagonist, they are actors in it. The other thing I liked about doing this film was that it’s like a mosaic of the arts. I could only suggest that new filmmakers experiment with the art form. It seems to me the only kind of films where there are no rules whatsoever. You can do a film only with archival footage for example. If you do interviews the right way, like with extreme close-ups, you can read so many emotions. All those elements are very exciting.

Peter Ettedgui: Working on Marlon was a revelation to me. We had his voice, so you have a certain authenticity. This is when I first started experimenting with documentaries. In the old days of editing you couldn’t do this, but with a non-linear timeline you can put together all these different kind of imagery that collide and contrast. Happy accidents often occur during this. Sometimes by juxtaposing images like this you can get results more powerful than in traditional storytelling.

Can you each pick your absolute favorite piece McQueen designed?

Ian Bonhôte: All the looks in “Plato’s Atlantis” are extraordinary. McQueen made a sci-fi movie almost. He created aliens. The shoes, makeup, how he transformed the girls is extraordinary. In terms of clothes though, some of the looks in “Highland Rape” are amazing. They have that punk, iconoclastic, anarchist style of Lee that spoke to everyone.

Peter Ettedgui: This is quite difficult. I might answer this a million different ways on a million different days, but as soon as you asked today I thought of one particular dress in the “Voss” collection. It wasn’t meant to be worn, it was a showpiece made out of razor clamshells that he and his then-boyfriend found on a beach in Norfolk. It’s just an extraordinary dress that shows his imagination. It goes into that love of the sea and nature that’s also present in “Plato’s Atlantis.” The way the dress is almost destroyed in the show has that taste of decay and death in it, that makes this less about the dress and more about the moment. There was another dress he made out of flowers that decayed during the show. It was from “Saraband,” and I’m not a great lover of fashion per se…

Ian Bonhôte: …that’s true, I have to tell him what to wear every day.

McQueen is now playing in limited release.