For our most comprehensive year-end feature, we’re providing a cumulative look at The Film Stage’s favorite films of 2019. We’ve asked our contributors to compile ten-best lists with five honorable mentions–a selection of those personal lists will be shared in the coming days–and, after tallying the votes, a top 50 has been assembled.

It should be noted that, unlike our other year-end features, we placed no requirement on a selection being a U.S theatrical release, so you may see some repeats from last year and a few we’ll certainly discuss more over the next twelve months. So, without further ado, check out our rundown of 2019 below, our ongoing year-end coverage here (including where to stream many of the below picks), and return in the coming weeks as we look towards 2020.

50. Bait (Mark Jenkin)

With all the talk of mermaids, wickies and wanks; you might have been led to believe Robert Eggers was the only director in 2019 to have honed a salt flecked, wind-whipped, early-20th-century aesthetic–the likes of Robert Flaherty–and applied it for their own contemporary needs. Thematically speaking, Mark Jenkins’ Bait–a punky, hilarious, playfully surreal, and beautifully honest reaction to the onslaught of gentrification in the idyllic fishing villages of his native Cornwall—might have seemed a million miles away from Eggers’ similarly brilliant Lighthouse, but its harnessing of outdated equipment and filmmaking techniques was no less astonishing, and perhaps more beautiful. It’s still seeking a U.S. distributor, so if you have to travel across the sea, it’s worth the trip. – Rory O.

49. Monos (Alejandro Landes)

There’s a preternatural feel to the opening sequences of Monos, the brutal, unflinching third film from Colombian-Ecuadorian filmmaker Alejandro Landes. As if we’re floating through clouds at the edge of the world, we witness a group of children, blindfolded, playing soccer, the fear instilled that a misaimed kick could send the ball hurling into the unknown oblivion below. With information patiently, sparingly doled out–even up until the final moments–we learn this tight-knit clan is, in fact, a rebel group in the mountains of Latin America, sporadically visited by a commander but mostly given orders through a radio. Intentionally suffocating in its aesthetic, cinematographer Jasper Wolf’s camera moves with a fierceness as the characters’ unpredictable movements dictate what our eyes follow. As an intense sociopolitical lesson, Monos certainly sheds vivid light on the costs of war in present-day Colombia, particularly when it comes to taking advantage of minds not yet fully formed. – Jordan R.

48. Us (Jordan Peele)

Jordan Peele’s follow-up to his Oscar-winning cultural touchstone Get Out is not as neatly packaged as its predecessor. The plot, which centers on a black family’s summer vacation being invaded by a group of doppelgängers, turns into a sprawling look at class dynamics set against the backdrop of Reagan-era America. Peele fills the movie with symbols and emblems, be they Michael Jackson or mysterious white rabbits. Us is so weighty that one might feel the need to immediately start it over once the credits roll. At its center is a canon-worthy performance from Lupita Nyong’o as a woman (and her doppelgänger) trying to outrun her past. – Stephen H.

47. América (Erick Stoll, Chase Whiteside)

As the United States goes through one of its darkest eras, filmmakers Erick Stoll and Chase Whiteside found the grace, compassion, and kindness lacking in their country through a different América: a 93-year-old Mexican woman with advanced dementia nearing the end of her life. Their camera captures daily life in her household, where she’s being looked after by her adult grandsons, with the delicateness of a caress, reminding us that objectivity in nonfiction is a lie. Why should a documentary be satisfied with being an indifferent eye when it can perfectly become a beating heart? – Jose S.

46. To the Ends of the Earth (Kiyoshi Kurosawa)

In which arguably the greatest living practitioner of interior spaces forces himself outside, all the more perversely in a country he’s never filmed. Whereas most filmmakers, even great ones, would use the displacement as an opportunity to gawk and play some easy notes about fish-out-of-water life, Kiyoshi Kurosawa created a paean to the perpetually lost–rarely has anything in any medium so succinctly captured the constant unease of international travel, nor its occasional terrors. Includes the single funniest gag involving a theme-park ride ever committed to film. – Nick N.

45. Blinded by the Light (Gurinder Chadha)

You don’t have to be a fan of The Boss to relate to one of the year’s most impactful coming-of-age films. Set in 1987 when Bruce Springsteen, an icon of the late ’70s, was starting to lose his edge amongst the youth, his music is discovered by Javed (Viveik Kalra), a boy from a traditional Pakistani family trying to find his way in the polarized climate of the Thatcher era. Directed by Gurinder Chadha, this late-summer crowd-pleaser delivers a sublime range of the emotions as Springsteen’s lyrics and biography merges into that of author Sarfraz Manzoor (whose memoir serves as the basis for the picture). At my screening (full disclosure: in New Jersey) Blinded by the Light was met with laughs, cheers and tears–exactly the kind of catharsis you’d associate with Springsteen at his best. – John F.

44. The Two Popes (Fernando Meirelles)

The Two Popes is the latest adaptation of Anthony McCarten’s novels, this time about Pope Benedict XVI (Anthony Hopkins) and Pope Francis (Jonathan Pryce). Benedict is known as “God’s Rottweiler” for his airtight approach to Roman Catholic doctrine, whereas Francis is known for his humble pastoral ministry, despite the luxury he’s expected to indulge as cardinal. Fernando Meirelles’ most accomplished film since City of God takes a granular look at the narcissism of small differences between men—who agree nearly 99% in matters of faith. It’s through their differences this two-hander shows how grace can compensate for failure to live by one’s vocation, values, etc. Hopkins and Pryce capture the public ethos of each pope’s distinctive approach to the world, and it’s McCarten’s screenplay, from the story to the images they invoke, that’s the film’s biggest strength. – Josh E.

43. Gemini Man (Ang Lee)

Ang Lee continues to push the boundaries of cinema. An ostensibly simple narrative, of an aging hitman evading a younger clone of himself, is rife with provocative symbolism surrounding the ways in which new technology has radically altered our relationships with time, space, and ourselves by blurring the lines between the real and the virtual. Armed with high-frame-rate cameras and a uniquely advanced CGI reproduction of one of the most charismatic actors alive, Lee expands the affective capacity of new digital technology and puts it all on display in an immersive viewing experience beyond the scope of human perception. Lee, in invoking this definitive alienation, highlights the “real” characters’ numbness towards their experiences or actions, radically reframing the emotional legwork around a set of digitally generated pixels and proving his humanity in turn. This, paired with some of the most inventive and well-realized action choreography of the year, recalls the ways in which early cinema technology was likened to magic acts. Gemini Man and the way in which it has been critically maligned indicates a potential changing of the guard; of all the films made this year for mainstream consumption, none are as singular as this. – Jason O.

42. Luce (Julius Onah)

So much of who we are relies upon perception when our reactionary society is too quick to judge on instinct without extending any benefit of the doubt. This is the impossible environment playwright J.C. Lee and director Julius Onah bring to life with Luce. They put a boy on trial without evidence–besides his accusers’ fears, since half-truths and assumptions will always be easier to embrace than simple explanations rendered complex by the inherent bias American entitlement provides as privilege. While Naomi Watts and Octavia Spencer are fantastic as hybrid judges/jury/witnesses, it’s Kelvin Harrison Jr. who steals the show once their characters force him to turn a heart-dropping disappointment at their lack of faith in him into the unyielding determination necessary for vindication. By the end we discover this truth: innocence is obsolete. – Jared M.

41. The Farewell (Lulu Wang)

The Farewell, written and directed by Lulu Wang, tells the story of a young Chinese-American woman (the great Awkwafina) who learns that her grandmother has been diagnosed with terminal cancer. The family elects to not tell the matriarch about the illness, deciding instead to throw a sham wedding as a reason for all relatives to come to China to say their goodbyes. Deeply personal yet achingly relatable, Wang juggles laughs and tears seamlessly, sometimes within the same scene. Zhao Shuzhen is magnificent as Nai Nai, the grandmother unbent by what she thinks is a nagging cold and unwillingness to stop commenting on the choices of each of her family members. God bless a movie that can be recommended to everyone. – Dan M.

40. The Wild Pear Tree (Nuri Bilge Ceylan)

Perhaps the daunting 190-minute runtime proved too intimidating and inaccessible for audiences to embrace. It’s a shame, because The Wild Pear Tree is one of the best films of the year: a soulful portrait of existential alienation set against a panoramic backdrop of Turkey’s countryside and coastal landscapes that are alternately majestic and melancholy. Ceylan’s masterpiece harnesses the ennui of modern Turkey to reflect on the world at large: art, metaphysics, religion, spirituality, death, morality, and how one’s connection to animals and nature is the ultimate salve against life’s pitiless and materialistic absurdity. The Wild Pear Tree is about how we choose to define our place in society, as Ceylan subtly pushes us to rethink our narrow notions of success and failure. With this film, he has fashioned a gentle and poignant odyssey—for his protagonist and for us viewers—towards inner peace, one that requires us to transcend the familial rifts, parental legacies and generational chasms that might stand in our way. To that end, its emotional gut-punch lies in its understanding that it’s the parent with whom we share the most fraught relationship—who we most resent and take for granted—that understands us to our core, and with whom lies the most sacred bond, tender love, and spiritual empathy—and how achieving this humbling revelation, while emotionally overwhelming, is the ultimate sign of personal growth. – Demi K.

39. Waves (Trey Edward Shults)

“You don’t know how lucky you are.” No other words prove more damning to show how out-of-touch a parent is with his/her child’s struggles. Rather than being emotionally present, they wield fear and disappointment en route to an explosion of insecurity and rage. Writer-director Trey Edward Shults ensures Waves‘ lead-up to that release is tough to watch with a violent act as linchpin seemingly gratuitous in the moment. Context, however, proves it’s paramount to the message. This script is contrasting duty to the group with duty to the soul as the former’s lie leads to turmoil, the latter’s truth to potential peace. Kelvin Harrison Jr. brings the pain. Taylor Russell strives to heal it. And Sterling K. Brown breaks our hearts upon realizing his character’s role in forcing them (his children) to suffer that fate. – Jared M.

38. Atlantics (Mati Diop)

Director Mati Diop made history as the first black woman to direct a film–her debut feature no less–that would be accepted into the official competition at Cannes (eventually winning the Grand Prix) with her perturbedly hypnotic, sensuous ghost story Atlantics. The haunting drama centers on the women left behind by their male loved ones who are tragically killed attempting to travel to Europe as a result of unpaid wages and then rematerialize to seek revenge. Diop crafts a film of seductively confounding beauty that combines startling social commentary and ghostly apparitions in a wholly original way. What an enormously bright future she has ahead of her. – Margaret R.

37. Honey Boy (Alma Har’el)

Shia LaBeouf’s staggering insight into his relationship with his father is one of the few films to understand the weight of parental-induced trauma, the way it shapes your entire being and the necessity to forgive yourself for their actions. Healing from these wounds is more complicated than words can describe, but LaBeouf writing a script about his childhood and playing his abusive father in the process is utilizing cinema as a medium of healing. This is a film about finding catharsis from your worst moments and memories. LaBeouf’s performance, particularly in its final moments, is revelatory, but it’s in the tired and frustrated young men (Noah Jupe and Lucas Hedges) he’s cast to play versions of himself that Honey Boy finds its truest connection. A work of art that can make living with your own pain easier. – Logan K.

36. Peterloo (Mike Leigh)

One of our great filmmakers, Mike Leigh, made a masterful epic about the tragic Peterloo Massacre of 1819 and nobody seemed to care. Framed as an ensemble, this film explores every angle of the impending event, from the young soldiers returning home from service to the local families running out of money as the Corn Laws take effect to the local politicians looking for a reason to punish their more rebellious constituents. There is such a matter-of-fact-ness to the work here, such a confidence in every frame. Leigh knows that this piece of history is relevant not because it’s extraordinary but rather that it’s brutally ordinary. As Brexit looms nearer and nearer, Peterloo serves as a reminder of that cyclical struggle between a government and its people. – Dan M.

35. Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story by Martin Scorsese

A chronicle posing as a prank within a historical drama dressed as biographical documentary in the comfortable concert-film mold. Correspondences with the reclusive (will Bob Dylan ever conduct another interview?), an invocation of the dead (Sam Shepard and Allen Ginsberg flow through proceedings as if no time has passed), the real playing fake, the fake presented as real. I think. Maybe reverse that order, or rearrange a couple of moving parts, or heed Bob Dylan’s advice: stop trying to follow as another would have it told and start seeing the thing for yourself. That a few manipulations with what’s true and what’s, let’s say, decided-upon could entirely upend what we expected may speak to its staid genre above all else, and still Rolling Thunder Revue is 2019’s blood-rush fever dream par excellence. Its trickery inspired this year’s liveliest debates, and to detractors I always suggest the same: take some of the greatest-ever footage of Dylan as consolation enough. Those who remain unmoved are simply not commuting with the same humanity. – Nick N.

34. The Lighthouse (Robert Eggers)

Confronted with the uncommercial aspects of a black and white, 4:3 aspect ratio, 19th-century seafaring tale, it’s a wonder anyone saw Robert Eggers’ brillant second feature. It’s even more impressive that it was one of the biggest independent films of the year. For whatever oddities his first film The Witch contained, Eggers doubles down on the strange, oscillating between dread and humor–often within a single scene. His Melville-inspired tale not only defies summary, but encompasses so many different genres that to label it horror alone is not only reductive, but misses the entire point. Come for the drunken revelry shared by Willem Dafoe and Robert Pattinson, stay for the mermaids. – Christian G.

33. High Flying Bird (Steven Soderbergh)

Throughout his decades-long career, Steven Soderbergh has yet to demonstrate a loss for formal innovation, let alone a lack of creative drive. His unconventional production model as of late–short, low-cost shoots that necessitate and embrace on-the-fly improvisation–has allowed him to go from experimental genre affairs, such as Unsane and Mosaic, to more widely accessible but no less eccentric studio fare, such as Logan Lucky and The Laundromat, within mere months of the previous production wrapping. High Flying Bird, shot on an iPhone 8 fitted with anamorphic lenses and edited largely in-transit, is the apotheosis of these late-career dispatches: spontaneously conceived and produced, somehow looking simultaneously sleek and rough-around-the-edges with an exhilaratingly anti-conformist attitude specifically attuned to the revolutionary history of black athletes. Don’t let looks fool you. Although High Flying Bird is primarily composed of dialogue-heavy sit-downs and walk-and-talks centered around an NBA lockout—where Moonlight scribe Tarell Alvin McCraney‘s stupendously sharp script shines—it is a reverent, potently radical film, both politically and technologically. – Kyle P.

32. I Was at Home, But... (Angela Shanelec)

Two years after the death of her partner, a mother of two is confronted with the reality of her teenage son’s incipient adulthood. Angela Schanelec evokes her protagonist’s existential torment by enshrining fragments of life in characteristically beautiful compositions. The comic absurdity of a failed attempt at buying a bicycle; a night-time visit to her partner’s grave as a mournful Bowie cover plays on the soundtrack; her children sitting on the front stoop after she’s thrown them out of the apartment in a paroxysm of rage. Meanwhile, a donkey, peaceful and lovely, spectates it all from another realm. – Giovanni M.C.

31. Knives Out (Rian Johnson)

Though this film—about a dysfunctional family vying for a fortune while trying to discover the circumstances behind the death of their patriarch—was perfectly poised for a near-Thanksgiving bow, it doesn’t take a lot of imagination to see this becoming a year-round classic. Overflowing with stunning performances from its soon-to-be-mythic cast and dripping with style from a production and cinematography standpoint, Knives Out became a late-stage awards contender overnight. But it’s the story by writer-director Rian Johnson that really cements this movie as top-of-the-year material. Not one to be missed. – Brian R.

30. Invisible Life (Karim Aïnouz)

Based on a 2015 novel by Martha Batalha, Karim Aïnouz’s Invisible Life is a tale of resistance. It hones in on two inseparable sisters stranded in–and ultimately pulled apart by–an ossified patriarchal world. It is an engrossing melodrama where melancholia teems with rage, with a tear-jerking finale that feels so devastating because of the staggering mix of love and fury that precedes it. It is, far and above, an achingly beautiful story of sisterly love. – Leonardo G.

29. Vitalina Varela (Pedro Costa)

The incomparable films of Portuguese director Pedro Costa have always hung heavy with the weight of their own austerity. The actress Vitalina Varela (for whom this shattering, scarcely classifiable film is named) had already appeared once before in Costa’s work—a supporting turn in 2015’s Horse Money–and yet nothing in that film could quite have prepared viewers for the levity she was about to bring. All of the Costa staples are present and accounted for here–static camera; subterranean lighting; Beckettian rigor; the alleyways of Lisbon’s Fontainhas neighborhood; God–but it’s through Varela’s performance that his latest reaches the cathartic and the sublime. – Rory O.

28. An Elephant Sitting Still (Hu Bo)

The suicide of debut writer-director-editor Hu Bo lingers over his four-hour Chinese drama An Elephant Sitting Still, as we witness four individuals wander the Northern Chinese city of Manzhouli in oppressive shallow focus and deliberate handheld tracking shots that acquire a sense of motion with no clear destination. But though the mournful musical motif and agonizing pace appear to register as repetitive and hopeless, there is something unique about the unbearable length. Elephant’s sprawling structure implies something beyond individual experience and its eventual destination reveals something strangely cathartic about the nature of that scope and shared, historical pain. Hu Bo was not interested in exploring duration as simply pain, but also compassion and beauty. He cared a lot about these characters and formally expresses his desire for more time with them, more time for them to find something new or maybe just find each other—and that he was able to so movingly and achingly express that (even if only finitely) is special. Wang Bing described Elephant as “A meteor passing through the dark sky,” and I’m inclined to agree. – Josh L.

27. Richard Jewell (Clint Eastwood)

Clint Eastwood’s conservatism has always been an easy target. While it is true that right-wing ideals manifest commonly in his work, his detractor’s arguments usually neglect to notice his more progressive values. In that sense, I’ve always interpreted his cinema as confronting a more vertical political structure–between those with power and those without. Richard Jewell, Eastwood’s latest celebration of working-class American heroism, traps its audience in the helplessness of its title character, who is falsely vilified by the FBI and media after preventing the bombing at Centennial Park during the 1988 Atlanta Olympics. It is some of Eastwood’s most emotionally devastating and unsettling work yet, deromanticizing core American values via contemporary cynicism and institutional insecurity. With enormous empathy, he reframes Jewell–embodied by a career-defining performance from Paul Walter Hauser–into a strangely relatable symbol of those betrayed by the very systems they trust. – Jason O.

26. The Beach Bum (Harmony Korine)

Treading a line between good vibes and pure evil, Harmony Korine’s The Beach Bum begins as what seems like a slack mainstream comedy (replete with hack music cues) before finding its footing as an odyssey through a certain strain of American unexceptionalism. Offering a vision that initially seems not as total as Korine’s past film, it’s perhaps the slyest work. Boasting stream-of-consciousness logic that puts other stoner comedies to shame, it offered images that were genuinely anarchic, romantic, and uproarious. An epic troll and a paen to life. Maybe all the best films have their cake and eat it too? – Ethan V.

25. La Flor (Mariano Llinás)

The fundamental details surrounding La Flor—its fourteen-hour run, its ten-year production, its appropriately devilish six-part structure—already have it predestined for cult status, yet Mariano Llinás’s mammoth effort both fulfill and far exceed any preconceptions. An extraordinary ode to forgotten genres, a sincere and open-hearted love letter to its four central actresses, who turn in some of the most astonishing performances in recent memory: what is perhaps most overwhelming about La Flor is that it manages to contain infinite worlds of pleasure, surprise, and glory, while paying tribute to the possibilities of cinema, storytelling, and human creativity. – Ryan S.

24. Glass (M. Night Shyamalan)

The idea of being defined by your otherness is both haunting and special. Depending on which differences you have, you are treated differently by the world. Some are praised for their unique skills, others are harassed into death. But no matter what, there is the persuasive cruelty of a society that doesn’t want anyone distinct to exist. In a year plagued by anti-vaxxers, ableist politicians, and continued hate crimes against disabled people, it is inspirational to see a filmmaker like M. Night Shyamalan correlate the treatment of us to the plight and significance of superheroes. While a lesser artist could have easily created offense, Shyamalan’s work has such deep empathy for its subjects that it emphasizes the cruelty of the way the world treats their others, yet finds beauty in the fact that people unlike the rest of the world can be critical in changing it for the better. Seeing a group of men who are told they’re weak, broken, and damaged alter the hopes of millions, even if they can’t witness it themselves, is something indescribable. – Logan K.

23. Hotel by the River (Hong Sang-soo)

Not that Hong Sang-soo ever makes a bad film, or seems barely capable of doing so, but if I found myself more smitten with his usual tricks—the granular conversations in a locked two-shot, the bright tones of a black-and-white palette, the blink-and-you’ll-miss futzes with structure, Kim Min-hee photographed with affection one only reserves for the person they love—it’s because this is maybe the first since Hill of Freedom (a best-of-decade-level work) that finds new ways to traverse his well-worn emotional landscape. – Nick N.

22. Hustlers (Lorene Scafaria)

There are no “little” women in Lorene Scafaria’s Hustlers, a generous, revelatory, genre-bending essay featuring some of the most iconic, larger than life characters of the year, all of whom happen to be women. An indictment on the corrosiveness of the patriarchy, a thrilling caper, and a warm portrait of alternative families, this Ocean’s Eleven-meets-Goodfellas drama features Jennifer Lopez in the performance of a lifetime. Combining the resilient spirit of The Grapes of Wrath’s Ma Joad and the ruthlessness of The Godfather’s Don Corleone–while hanging upside down from a stripper pole–she created an amoral heroine for all eras. – Jose S.

21. Under the Silver Lake (David Robert Mitchell)

In our desperate need to explain the inexplicable, to create order out of chaos, it’s tempting to see messages when there aren’t any. But David Robert Mitchell’s go-for-broke, playing-with-house-money film Under The Silver Lake poses a scarier proposition: Maybe the messages are there, except they’re essentially meaningless. Sam (Andrew Garfield, in the best role of his career), a paranoid slacker who finds clues baked into pop culture detritus, tumbles into a not-so-absurd conspiracy—wealthy elites who yearn to be Gods secretly plan to escape a decaying society—but it only highlights his own irrelevance in the face of the world’s grander machinations. After all, it’s way too easy to miss the forest for the trees. – Vikram M.

20. Her Smell (Alex Ross Perry)

Alex Ross Perry’s rock-and-roll epic is more than just a vehicle for the performance of the year, which belongs to Elisabeth Moss’s spiraling, ferocious Becky Something. In this indelible portrait of addiction, the corrosive nature of fame, and the unbreakable bonds amongst female artists, Perry focuses on a very specific musical era–one not often depicted in our biopic-obsessed landscape–and he makes every single frame feel deeply rooted in its history. A film as mournful about time’s passage as The Irishman or Once Upon A Time… in Hollywood, but with an admittedly brief glimmer of hope. – Stephen H.

19. Dragged Across Concrete (S. Craig Zahler)

With Bone Tomahawk and Brawl in Cell Block 99, writer-director S. Craig Zahler staked claim to the title of best provocateur in modern American filmmaking. This year, he doubled down on that claim and also showed exactly what one could do by valuing story and character over good taste and social nicety. Dragged Across Concrete is a wild mashup of Heat, Lethal Weapon, and a Chekov play: violent, funny, and weirdly moving. Packed with tense action, gruesome gore, and long stretches of pulpy, quotable dialogue, this is the crime film to beat for the next decade. – Brian R.

18. High Life (Claire Denis)

in High Life, Claire Denis’ haunting small-scale space epic, the human race has finally reached the point where people become expendable commodities at the cost of finding infinite recourses in a black hole lightyears away. Dually laced with love/fear, hope/perversion, and desire/desperation, the screenplay wrestles with human nature pushed to its unnatural limitations. This messy fine line is illustrated over and over through screaming babies, gardens with dead bodies, dropping lifeless corpses into the vast silence of space, and, of course, the infamous “fuck box.” Denis explores these themes with brilliant insight, never losing an ounce of momentum and always maintaining some semblance of hope. – Murphy K.

17. Synonyms (Nadav Lapid)

Following Policeman and The Kindergarten Teacher, Nadav Lapid’s Golden Bear winner completes an unofficial trilogy on Israeli identity, and confirms the director as one of the most invigorating cinematic talents to emerge in the last decade. In a prodigious debut performance, Tom Mercier plays an Israeli ex-soldier recently arrived in Paris as a mix of Travis Bickle and John Carpenter’s Starman. That we can’t decide whether he’s a psycho or a holy fool represents just one of the many irresolvable ambiguities that propel Lapid’s ferocious confrontation with this most contentious of thematics. – Giovanni M.C.

16. Asako I & II (Ryūsuke Hamaguchi)

Full-fledged, complicated, rapturous romance is relatively rare in cinema nowadays, and one of the very best examples is Ryūsuke Hamaguchi’s Asako I & II, which uses its doubled lovers as a way to reflect back upon its main character, in all of her doubts and uncertainties. Deeply rooted in its present moment, yet prone to flights of fancy as transportive and unreal as any in contemporary filmmaking, the film delights as much as it aches, staying in close step with the turns caused by the whims of the self and the other, moving back and forth in rapture. – Ryan S.

15. Little Women (Greta Gerwig)

Greta Gerwig’s new take on an American classic was, simply, why? That Gerwig answers that question by repurposing the story of the March sisters, chopping up Alcott’s linear narrative to better understand the relationship between love and friendship, is profound in its own right. Each of the sisters is distinctive, as Gerwig leads with humanity, foregrounding the innate good within the March family, and for perhaps the first time, makes the triangle between Jo, Laurie, and Amy relatable. The definition of a perfect family film, Gerwig updates Little Women with losing Louisa May Alcott’s prescient vision of female adulthood and proves that, with the right voice, certain stories will never lose their timelessness. – Christian G.

14. The Souvenir (Joanna Hogg)

Marooned on remote islands and unwelcoming family gatherings, clinging onto homes and objects as if they were protruding limbs, people dot Joanna Hogg’s universe as they struggle to heal and begin anew. Nowhere does that feeling ring as personal and vivid as it does in The Souvenir–Hogg’s exhumation of her devastating relationship with an addict that ran through her film school years. Her stand-in is Honor Swinton-Byrne’s Julie, her lover Tom Burke’s Anthony. In a film that unspools as an act of recollection, down to David Raedeker’s grainy cinematography, their onscreen chemistry brims with the energy and sadness of a resurrected first love. Even as it exposes Anthony as a manipulative and beguiling wrecking-ball, and Julie as a naive safety net he can always fall back on, The Souvenir grants them empathy in equal measure. This is a charitable story, and Hogg’s ability to understand and forgive her characters’ failings may be its crowning glory. Burke is stupefying as the elusive and feverish Anthony, but it’s in Swinton-Byrne that The Souvenir finds its beating heart. Her performance turns it into a lacerating film–one of the few this year in which you can sense the pain in the telling. – Leonardo G.

13. Midsommar (Ari Aster)

A step up for writer-director Ari Aster in every way, Midsommar releases the stifled interiors of Hereditary for a more flowing, organic, and audacious horror odyssey. The film follows Dani (Florence Pugh) from family tragedy at home to a Swedish festival with her unenthused boyfriend (Jack Reynor) and his grad school buds. Soon, melodrama unfolds and hallucinogenic drugs are ingested in equal doses until everything spills out into madness. Aster works with wide frames and deep focus photography to immersive effect, elevated by Pugh’s next-level performance and a clever blend of sound and visual ingenuity. It all builds toward a coda that finds perverse but authentic catharsis, delivered as a shattering exhalation of grief, trauma, and what happens when we settle for less. – Michael M.

12. Long Day’s Journey Into Night (Bi Gan)

One of the most staggering cinematic experiences of the year was seeing Bi Gan’s transportive, dreamlike odyssey Long Day’s Journey Into Night in 3D. Mirroring the structure of his stunning debut Kaili Blues, it concludes with an astounding hour-long single take through (and above) multiple towns as we follow a detective’s journey to track down a mysterious woman. It’s become a go-to description to describe beautiful cinematography as dreamy, but what this emerging, brilliant director understands is how to cinematically translate the rhythms of such a subconscious experience in all of its isolation and wonder. He may be influenced by the likes of Wong Kar-wai and Andrei Tarkovsky, but Bi Gan is firmly charting his own path into unknown territory the likes of which have never been explored so thoroughly in film before. – Jordan R.

11. Ash is Purest White (Jia Zhangke)

Jia Zhangke focuses on the prism of displacement: social, economic, political, spiritual. Ash Is Purest White, his latest dalliance with genre-inflected cinema, portrays a modern China stimulated and disrupted by the effects of globalism. But even as these changes motivate every aspect of the recursive narrative, they’re adjacent in this dual character study of a gangster and his moll. This film’s interest in time proves more platonic and freely cinematic as these characters travel through a world that’s left them behind. – Michael S.

10. Portrait of a Lady on Fire (Céline Sciamma)

In a year of tremendously moving cinema, no film was as mesmerizing, as passionate, and genuinely overwhelming as Céline Sciamma’s Portrait of a Lady on Fire. It is an emotional experience at once familiar–the immersion into the past of The Piano, the window into the artistic process of La Belle Noiseuse, the thwarted romance of The Age of Innocence–but in the hands of Sciamma and stars Noémie Merlant and Adèle Haenel, it feels wholly original. Within minutes–perhaps the first glimpse of the haunting painting of a “lady on fire”–Portrait feels like a classic film. It ends on a moment of sublime sadness, yet leaves the viewer in a state of ecstasy. An extraordinary achievement. – Christopher S.

9. Marriage Story (Noah Baumbach)

Noah Baumbach has always been keen on injecting his real-life struggles into material, but never has it been as visceral and literal as with Marriage Story. Combining his trademark wit with wholly devastating moments, the writer-director masterfully captures the intensity of a marriage torn apart by subtle rifts that fester into debilitating wounds. Adam Driver and Scarlett Johannsson navigate these nuanced emotional beats with a raw intensity that traverses the emotional spectrum over and over. Each moment of levity is later matched with instances of quiet profundity that, especially when coupled with Randy Newman’s score, leave a lasting impact of melancholic optimism. – Murphy K.

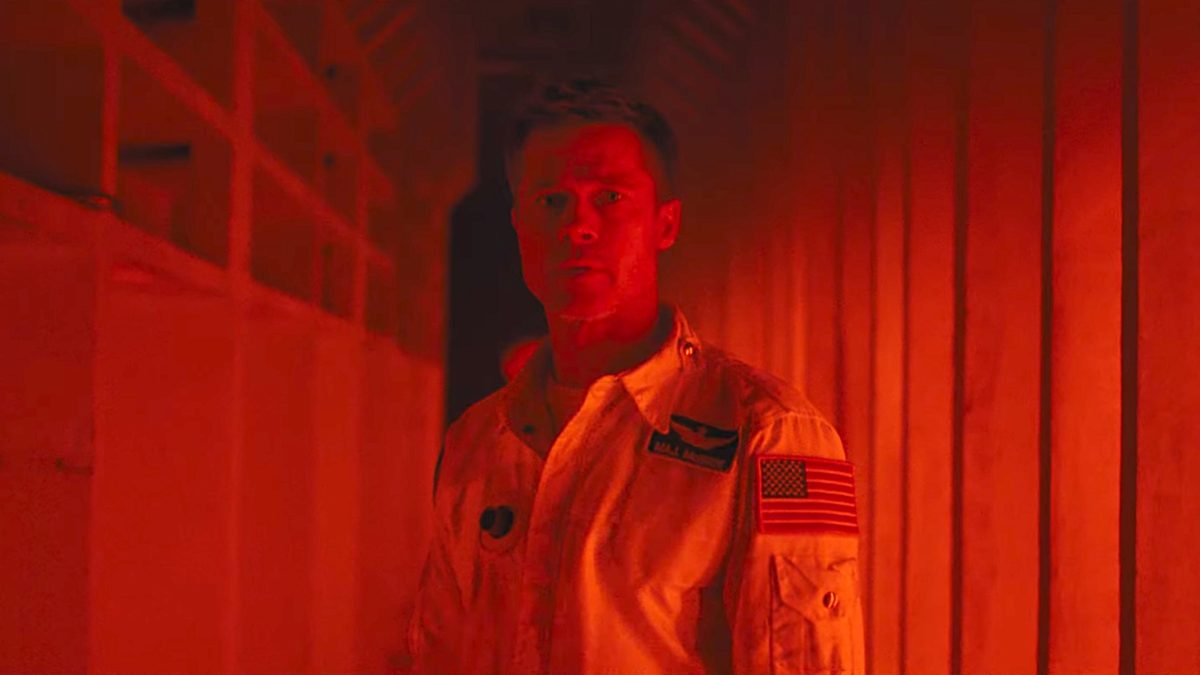

8. Ad Astra (James Gray)

Ad Astra is the rare, beautiful marriage of auteurist vision and studio resources that restores the wonder of sci-fi while exploring the depths of the human mind. Aided by an across-the-board excellent technical team including cinematographer Hoyte Van Hoytema and composer Max Richter, Gray weaves themes of Shakespearean gravity into an immaculately crafted space adventure that thrills as much as it challenges and moves. Brad Pitt delivers a subtle, soulful performance, syncing this biblically ambitious film with the pulse of a gradually awakened heart. Looking fearlessly outwards and even more boldly inwards, Ad Astra offers a contemplation of our existence that transfixes and humbles. – Zhuo-Ning Su

7. Uncut Gems (Benny and Josh Safdie)

Those unfamiliar with New York filmmaking duo Josh and Benny Safdie may find it strange that a movie primarily consisting of Adam Sandler desperately scheming and sweating his way all across New York City streets, cabs, and venues in garish Gucci shirts and loafers is among the year’s best. But Uncut Gems—in all its loud, anxious, and street-textured controlled chaos—is a stylish, heart-breaking, near-perfect culmination of their cinematic affection for the art and craft of hustling that give their movies a sense of propulsive energy, and their deceitfully upsetting focus on the rippling consequences of that craft: of weaponizing social relationships as transactional ones and ignoring the class realities of people on the opposing side. – Josh L.

6. Pain and Glory (Pedro Almodovar)

In Pedro Almodóvar’s intimately confessional drama about an aging filmmaker reconciling with a life of achievements and heartaches, everything is reduced to its purest form. There are no stunts, no tricks, no hurry. One instead finds themselves captivated and emotionally shattered by the wise, gentle voice of a master storyteller who has nothing left to prove. As his stand-in, Antonio Banderas commands the screen with an equally unflamboyant, minutely lived-in performance that lingers with palpable warmth. Watching both of them at work is to experience cinema at its most truthful and transcendent, something so vividly, sincerely realized it feels less orchestrated than simply remembered. – Zhuo-Ning Su

5. A Hidden Life (Terrence Malick)

In Terrence Malick’s The Thin Red Line, conflicted American soldier Pvt. Witt (Jim Caviezel) tries in vain to dodge the horrors of war on Guadalcanal Island. Austrian farmer and conscientious objector Franz Jägerstätter (August Diehl) feels similarly trapped by the creeping influence of Nazi ideology in A Hidden Life. In that regard, Malick’s haunting new WWII epic can be seen as his prison movie, marked by vast mountains and valleys instead of walls and a constantly evolving philosophical escape from tyranny. – Glenn H.

4. Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood (Quentin Tarantino)

In his third stab at rewriting history, Quentin Tarantino paradoxically uses specificty to make his most sprawling and ambitious film to date. Taking place over two days and one infamous night, Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood sees Tarantino ditching plot as it follows a washed-up actor (Leonardo Dicaprio), his stuntman (Brad Pitt), and Sharon Tate (Margot Robbie) going about their business in 1969 Los Angeles. Once one gets accustomed to the relaxed pacing and emphasis on character over story, it’s apparent that Tarantino is trying something much different from Inglourious Basterds and Django Unchained. This is about using our knowledge of the past to create a new, lived-in space based on it, where people forgotten by history can shine and victims can be remembered for who they are instead of where they ended up. In a decade where fantastical and escapist entertainment have dominated and monopolized cinemas, Tarantino pushes the concepts of escapism and fantasy into risky and uncharted territory. Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood uses cinema to let us spend time in a world where we can see a part of history have a happy, Hollywood ending, smashes it against our knowledge of reality, and lets us sift through the wreckage. – C.J. P.

3. Parasite (Bong Joon-ho)

Over the course of his career, Bong Joon-ho has come to define himself as a maestro of the tonal tightrope, and Parasite continues that immaculate balance. Devilishly funny, equally tender, and more than a bit depraved, this deconstruction of contemporary economic class and status nimbly executes a constant subversion of its character dynamics. With pitch-perfect timing on its rug pulls, the film’s dexterity with comedy, horror, suspense, and outright tragedy is punctuated by a commanding cast, who collectively give some of the best performances of the year. In unsure hands, Parasite could have been rendered an untenable mess. Bong’s brazen commitment delivered a richly textured, empathetic, and deeply affecting masterwork. – Conor O.

2. Transit (Christian Petzold)

Though German filmmaker Christian Petzold built a cachet for twisty, sumptuous riffs on Alfred Hitchcock with Phoenix and Barbara, this reputation obscures that his films are inherently about communication and the layers of interference making that interaction so difficult. His glorious Transit lays bare that notion, from its framing of an enigmatic but empathetic narrator to its knowingly obtuse narrative of mistaken identities and bait-and-switches–nonetheless punctuated by half-a-dozen meaningful conversations with near-strangers. – Michael S.

1. The Irishman (Martin Scorsese)

Our favorite film of 2019 tells the tragic story of a man who shook the hand that shook the world, then shot the owner of that hand in the head. It’s the inevitable conclusion to the lifestyles Martin Scorsese portrayed in his past crime epics, such as Goodfellas, Casino, and even The Wolf of Wall Street. We’re just not ratting on our friends anymore. Oh, no–it’s much worse than that. An evocative and heartbreaking look back at a life woefully misspent, The Irishman–or I Heard You Paint Houses, depending on which title card you believe–reunites Scorsese with Robert De Niro and Joe Pesci for the first time in nearly 25 years, their aging (and yes, sometimes de-aged) faces instilling their stunning performances with a wistful poignancy. – Tony H.