After highlighting the 50 best films you may have missed this year and our overall top 50 films of 2025, today we put our spotlight on those that still need a home: movies we loved on the festival circuit––from Berlinale, Sundance, Cannes, TIFF, NYFF, Rotterdam, and beyond—still seeking U.S. distribution.

We hope that highlighting these titles spurs some distributor interest and a forthcoming release; we’ll be sharing any updates in this regard on social media, so make sure to follow us. As we move into 2025, one can also track our upcoming festival coverage by subscribing to our daily newsletter.

Afterlives (Kevin B. Lee)

So much of filmmaking and film-watching boils down to either lending your eyes to another or accepting that loan as a viewer––a process so quick, so immediate when done right that one can easily forget it’s about exchanging consent. To look away, to close your eyes and cover your ears, to leave the room, to close the tab: all these acts seem simple and innocuous when taken out of their “spectatorial” context, but what effective cinema shares with the graphic images of violence circulating on our feeds is how horrendously watchable it is, to the viewer’s detriment. Afterlives, the debut feature by Kevin B. Lee, which screens as part of the BFI London Film Festival’s Experimenta programme off the back of its world premiere in DocLisboa, asks whether there is a way to see such images without showing them; to care, without avoiding them. – Savina P. (full review)

Ari (Léonor Serraille)

French director Léonor Serraille’s third feature Ari is the portrait of an über-sensitive young man who ponders his place in the world while looking up people from his past to hold conversations that were never had. If this sounds like the premise for a parody of talky French dramas, for a while it really does suggest one––until the perceived tropes and stereotypes fall away to reveal a raw, humanist core that’s anything but clichéd. – Zhuo-Ning Su (full review)

Barrio Triste (Stillz)

At barely two years old, Harmony Korine’s “post-cinema” company EDGLRD is already branching out. After directing AGGRO DR1FT and Baby Invasion, Korine takes on a producer role for Barrio Triste, the feature debut of Colombian-American artist Stillz. It’s a good match of talents, given Stillz’s background as a music video director for artists like Bad Bunny and Rosalia, and while Barrio Triste takes a vibes-based approach à la Korine’s last two features it’s an entirely different beast. Exhilarating, tense, personal, and enigmatic, Barrio Triste is a compelling look at a lost generation in search of salvation, and among this year’s best first features. – C.J. P. (full review)

Brand New Landscape (Yuiga Danzuka)

When confronted with the past, do you drive away or turn back to face it? Siblings Ren (Kurosaki Kodai, in his first lead role) and Emi (Mai Kiryu) have been estranged from their father (Ken’ichi Endô) for the ten years since he chose a new work opportunity in Tokyo. Ren, now a florist, notices a familiar name on the neighboring workstation’s order card. Propelled by emotion, not logic, he takes on the delivery himself, arriving to discover his father staring back at him through the floor-to-ceiling window of a major exhibition. Clutching the arrangement tight to his chest, there’s a heavy burden to carry. – Blake S. (full review)

Eel (Chu Chun-teng)

The most significant change introduced by new Berlinale director Tricia Tuttle is the cancellation of the Encounters sidebar which hosted many arthouse gems supposedly too experimental for the main competition. In its stead, Perspectives––a competitive section dedicated to first films––was created. Its inaugural edition includes Eel, the feature debut of Taiwanese visual artist Chu Chun-teng. Gliding between genres and styles, the film is as slippery as its namesake and may not satisfy those who prefer to understand what they see onscreen. Regardless of how one rates its success as a work of narrative storytelling, Eel certainly announces the arrival of an exciting new voice. – Zhuo-Ning Su (full review)

Escape (Masao Adachi)

Though a contemporary to the Japanese New Wave, Masao Adachi has spent much of the last six decades as a revolutionary figure on political stages. Escape suggests the logical distilling of artistic and personal histories: a biopic of Japanese terrorist Satoshi Kirishima, who spent nearly 50 years as one of the country’s most wanted men before revealing his true identity on his deathbed. Adachi tells Kirishima’s story—always remarkable, often troubling—in a dazzling mix of archival footage, staged recreations, and outright fantasy, the film coming to double as a history of resistance and terror in Japan. A New York Film Festival debut notwithstanding, Escape received minimal attention stateside—looking like it costs $0 doesn’t quite help its case. One hopes a distributor paying the right kind of attention to the current cinema gives Adachi, who’s not likely to make many more films, better platform than any stateside entity’s bothered. – Nick N.

Evidence (Lee Anne Schmitt)

A highlight of New York Film Festival’s Currents lineup, Lee Anne Schmitt’s invigorating essay film Evidence captures the ills of modern American conservatism through a very personal lens. With the through line of exploring family history, the director weaves fascinating threads about corporate environmental destruction, the stranglehold of right-wing media, and the devious ways Republican officials get elected. A work of investigative journalism that has a formal and emotional backbone like few others of its ilk, Evidence is a must-see. – Jordan R.

The Fence (Claire Denis)

Is the idea of a Claire Denis film changing? There was likely an image one formed in their head when that name emerged: elliptical, sexy, avant-garde. Yet recent works are suggesting a different direction, one far more direct and less mysterious. It can even be said that her newest, The Fence, plays like a final film––not necessarily as a grand summation or statement, but like a stripping-down of almost everything possible. The film, one can say, comes to be just about the politics––or perhaps if you asked Denis, a known fan of the wordy Jean Eustache, character and dialogue––instead of capital m-e-s mise-en-scène. Being based on Bernard-Marie Koltès’s play Black Battles with Dogs, its stagey origins serve it to both effective and detrimental ends, and also point to someone just wanting to knock out an adaptation of something they liked rather quickly. – Ethan V. (full review)

Fucktoys (Annapurna Sriram)

Playing like the kinkier granddaughter of Russ Meyers’ Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill!, Annapurna Sriram’s Fucktoys has an axe to grind, and then some. At its core, this is a critique of modern capitalism that feels increasingly relevant, arriving in a time when billionaires are forcing the middle and lower-middle class to go on a diet budget. Younger people have been squeezed, left behind, and fucked-over by a massive transfer of wealth and, in turn, some have viewed young generations as a commodity to project their fantasies. In essence, if you’re unlucky in this economy, you might find yourself becoming a fucktoy. Needless to say, this is a film that’s not safe for work or polite society. – John F. (full review)

Gavagai (Ulrich Köhler)

A perpetually underrated figure in world cinema, Ulrich Köhler (In My Room) returns with something like a major statement. In a metacinematic spin on Medea, a pair of actors (Jean-Christophe Folly and Maren Eggert) film Euripides’s play in Senegal under the guise of an anxious director (Nathalie Richard) while carrying an offscreen affair; a later incident at its Berlin premiere opens tough questions about bias and intent. Per Köhler’s standard, Gavagai locates the sweet spot between tense, despairing, and genuinely funny. – Nick N.

The Kingdom (Julien Colonna)

Vito Corleone once asked, “You talk about vengeance. Is vengeance going to bring your son back to you? Or my boy to me?” Stories of revenge tend to acknowledge its messy, tragic, futile consequence, but ultimately it’s too powerful a compulsion to resist. Revenge is surreptitiously the inciting incident for Julien Colonna’s unassuming The Kingdom. It follows Lesia (played by promising newcomer Ghjuvanna Benedetti), a teenage girl concerned with school and boys who is then whisked away to her other life as the daughter of the head of a Corsican mafia family. Lesia is perturbed by her dual life, but her longing for family and particularly the affection of her father (played by Saveriu Santucci). As the cinematic mafia life has shown, the bonds are strong but their existence is frail as one-by-one, her loved ones get ensnared in a territorial battle. Colonna weaves together a touching portrait of a father-daughter relationship with a textbook mob conflict. It’s The Godfather meets Aftersun. After Metrograph Pictures’ collapse released the rights this year, it’ll hopefully finds a new home soon. – Kent M. W.

Late Fame (Kent Jones)

It is early into Kent Jones’ Late Fame when Ed Saxberger (Willem Dafoe) joins a coterie of twenty-something wannabe intellectuals for a drink in the Village. This is Saxberger’s scene––better yet, was. A one-time poet, he hasn’t written anything after his first and only book came out in the late 1970s, whereupon he retreated into anonymity, serving as a different man of letters at NYC’s post office for almost 40 years. But when a budding writer one-third his age shows up at his doorstep to beat the drum for his forgotten literary endeavor, Way Past Go, Ed doesn’t quite know how to react. “It’s as if the poems were written yesterday,” Meyers (Edmund Donovan) croons, before inviting the grizzled bard to a drink with his new fans (a token of “inspirationally motivated gratitude”). Ed hesitates; when he finally caves, Jones lingers on Dafoe’s face as the meeting with a rapt audience rekindles something in him. Call that a re-self-discovery: surrounded by a gaggle of youngsters who treat him with reverential respect, Ed is suddenly reminded of who he was, who he still is. Stunned by this epiphany, Dafoe smiles, and the film smiles with him. – Leonardo G. (full review)

Love on Trial (Koji Fukada)

What is love? For some, it is mutuality––a chemistry, care, and concern that blossoms into an equally supportive relationship. For others, it is devotion––a one-sided, obsessional affection that the lover finds selfless. Japanese idol group Happy Fanfare sing about love, but they’re not allowed to pursue their own––such is the “No Love” clause present in their contracts. Their romantic isolation is deemed vitally important to the business of idol stardom, allowing their male fans to hold onto the fantasy of the attainable yet unattainable female. This ideal is perpetuated by meet-and-greet sessions where the quintet express fond recollection of fans’ past gifts and comments. A parasocial relationship is nurtured, but the cracks start to show when reality creeps in. – Blake S. (full review)

Nuestra Tierra (Landmarks) (Lucrecia Martel)

There is a direct and conscious through-line between Lucrecia Martel’s previous historical film Zama to her contemporary legal documentary Nuestra Tierra. We see the lives of indigenous communities in Argentina continue to be treated with little regard and a clear class and racial fissure exists in the nation. Martel films the court scenes and the footage of the disputed land as two battlegrounds spanning time. The murder of the Chuchagasta indigenous community leader Javie Chocobar at the hands of corrupt businessmen and bureaucrats reflects and mirrors the history of Argentina as, to this day, a disputed territory. While Martel’s cinema is known for its heavy use of metaphor, blending of fantasy and realism with impressionistic camerawork, this is a movie that pares everything down to cinema’s base elements, making crystal clear what is at stake. – Soham G.

I Am Frankelda (Arturo Ambriz, Roy Ambriz)

More than the similarly mythologized Monsters, Inc., the first stop-motion feature produced in Mexico (courtesy of the Cinema Fantasma studio) recalls an old childhood favorite from the ’80s: Little Monsters. Just like that Fred Savage vehicle, writers-directors Los Hermanos Ambriz (Arturo and Roy) have created a means to connect reality to nightmare so a human might embrace the latter’s mischief, mystery, and terror that the former rejects. The 19th-century-set I Am Frankelda is thus born from a young woman’s mind (Mireya Mendoza’s Francisca Imelda) as a manifestation of her aspiration to become a horror writer––a dream met with major pushback from publishers, society, and family alike. – Jared M. (full review)

The Plant from the Canaries (Ruan Lan-Xi)

Never underestimate the critical desire to cite Éric Rohmer––spend enough days at a film festival and you’ll start noticing illusions to the director’s work in your breakfast cereal. Still, I’m struggling to think of a recent film that’s done so much with Rohmer’s style as The Plant from the Canaries, a debut of rare clarity, wit, and beauty. It might be the best thing I saw in Locarno this year. – Rory O. (full review)

Pin de Fartie (Alejo Moguillansky)

Since the early 2000s, the fiercely independent Argentine filmmaking collective El Pampero Cine has built a sui generis filmography by shirking conventions. A catalogue that includes Mariano Llinás’ 13.5-hour La Flor and Laura Citarella’s 4.5-hour Trenque Lauquen doesn’t exactly make it easy. Yet those who groove with Pampero’s beat will attest to the singularly rewarding experience of giving oneself over to their films. Pin de Fartie, the latest from co-founder Alejo Moguillansky, clocks in at a very reasonable 106 minutes. How it expands on and deconstructs one of the 20th century’s defining absurdist plays will send one’s head spinning nonetheless. – Zhuo-Ning Su (full review)

Remake (Ross McElwee)

Though best-known for his landmark reflexive documentary Sherman’s March, Ross McElwee crafts his most aching, personal film yet with Remake. Partially structured around McElwee’s process when a company hopes to adapt Sherman’s March, its true nature soon reveals itself: a tribute to the director’s son and self-reckoning as McElwee ponders his hand in his son’s path. It’s a nakedly confessional, deeply emotional work that will break any parent’s heart into a million pieces. – Jordan R.

Sham (Takashi Miike)

A workmanlike procedural that does more to suggest a Clint Eastwood drama than the kind of unhinged thriller one’s come to associate with great auteur Takashi Miike, Sham is surprisingly straightforward. The story follows a teacher accused of abusing a student and the ensuing fight to clear his name. Like an Eastwood drama, the focus is largely on its flawed central character; here it’s Seiichi Yabushita (Go Ayano), an elementary school teacher who harbors a bias towards Takuto (Miura Kira), a student of mixed Japanese-American heritage. In the opening sequence, he arrives on a rainy night in 2002 to his house for a parent-teacher conference with mother Ritsuko Himuro (Ko Shibasaki) and seemingly makes several off-color comments about the boy’s “mixed blood.” – John F. (full review)

Two Pianos (Arnaud Desplechin)

The past rears its not-so-ugly head in Two Pianos, Arnaud Desplechin’s latest film exploring the ways gorgeous people make an even bigger mess out of the messiness of life itself. Set amidst the world of classical music in Lyon, this tale of a tortured pianist’s reunion with his also-tortured first love contains the literary and melodramatic elements one normally expects from Desplechin, who––having not received a theatrical release since 2017’s Ismael’s Ghosts––has unfortunately fallen out of favor in the U.S. Fortunately that’s not the case in his home country, where he’s maintained a prolific output that continues attracting some of France’s top actors. With Two Pianos he’s put together a rich, thoughtful look at how we can shape our lives around our biggest regrets. – C.J. P. (full review)

Two Times João Liberada (Paula Tomás Marques)

Amongst the debut features populating Berlinale’s new section called Perspectives, none presented so admirably fresh take on fiction and political histories as Two Times João Liberada. The Portuguese hidden gem is directed by Paula Tomás Marques, who has made a few captivating shorts and also worked as a cinematographer on others’ films (including Matiás Piñeiro’s You Burn Me) as well as being an editor and script supervisor. Given her all-round involvement with independent production, it’s little surprise her full-length debut is a film about the making of a film. In the Lisbon-set João Liberada, an actress named João (June João, collaborator of Marques on shorts and performance) is cast to play a namesake of hers in a micro-budget period film. – Savina P. (full review)

The Visitor (Vytautas Katkus)

There are big things happening in Lithuanian cinema at the moment, many of which have barely touched New York screens. Vytautas Katkus’ The Visitor might be the best evidence that American cinephiles should take more notice. Winner of this year’s Baltic competition (consistently the festival’s strongest section), The Visitor is an atmospheric and contemplative film with a strong sense of slowly building absurdist humor. It follows Danielius (Darius Šilėnas), mid-30s and newly a father, as he returns to his hometown to sell his childhood apartment. With few friends and nothing concrete to do, Danielius spends his days walking aimlessly through the forest, floating in the ocean, dozing sporadically in various public places, and looking longingly at karaoke singers from the fringes of local bars. – Joshua B. (read more)

We Are Storror (Michael Bay)

Allegedly submitted to SXSW without the name of its director attached, Michael Bay’s feature-length non-fiction debut We Are Storror is a breathtaking action documentary that demands to be seen on the biggest screen one can find. Storror follows a close-knit band of seven free-running parkour athletes (including two groups of brothers) who create a series of stunts that defy gravity and logic, in the process breaking bones and building a following of 11 million on YouTube. – John F. (full review)

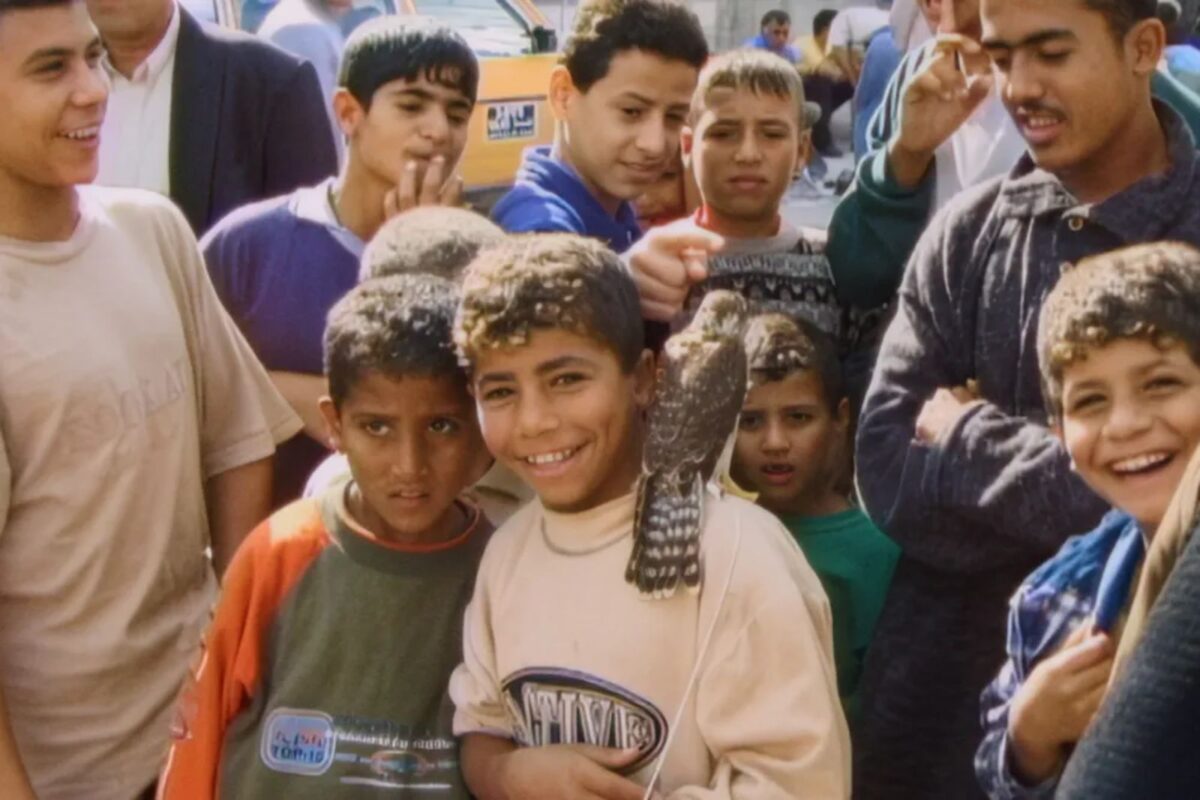

With Hasan to Gaza (Kamal Aljafari)

The new documentary With Hasan in Gaza––a poignant, meditative portrait of a city now fighting for its life––works as both a travelogue and time machine. In 2001, the filmmaker Kamal Aljafari journeyed to Palestine in the hopes of finding Adder Rahim, a friend he made while serving seven months in the juvenile section of Israel’s Naqab Desert prison when he was 17 years old. During filming, Aljafari met Hasan, a guide who agreed to drive him the length of the country, down its coastal strip, during which time the director documented what he saw: children playing, rows of cars and buildings, bustling city streets. – Rory O. (full review)

More Recommended Films in Need of Distribution

- Amoeba

- Anything That Moves

- Bad Apples

- The Bend in the River

- Blue Film

- The Botanist

- Duse

- End of History

- Enzo

- Fuze

- Ghost Boy

- Growing Down

- Hair, Paper, Water…

- In the Glow of Darkness

- I Only Rest in the Storm

- Last Night I Conquered the City of Thebes

- Levers

- Lockjaw

- Outerlands

- Paul

- Rains Over Babel

- Rewrite

- Room Temperature

- The Scout

- A Story about Fire

- Terrestrial

- The True Beauty of Being Bitten by a Tick