One day, you will die. It may not be tomorrow––as the characters in Amy Seimetz’s vivid, unsettling new feature She Dies Tomorrow believe––but it’s a universal truth for us all. To celebrate the film’s release, or at least cope with corporeal impermanence, we’ve shared our favorite films that explore mortality.

A handful of the below selections may comfort you as we collectively march into the sweet embrace of death, others provide a distressing glimpse at our body’s demise, and some explore all that humanity can offer––a feat which poses the question of what one is doing with their time before shuffling off this mortal coil.

A.I. Artificial Intelligence (Steven Spielberg)

In thinking about mortality, it’s often zooming out to the big picture and mysteries of our galaxy that can induce the most existential of questions. Steven Spielberg understood this with grand poignancy in his sci-fi epic A.I. Artificial Intelligence, first developed in the hands of Stanley Kubrick. The story of what it means to be human and all the emotions it entails, A.I. is an ambitious articulation of one’s lifelong quest for acceptance––even after all of humanity is extinct. – Jordan R.

All That Jazz (Bob Fosse)

A decade before he would die at the age of 60 from a heart attack, Bob Fosse directed one of the greatest films about death. This semi-autobiographical story of a director and choreographer (Roy Scheider) trying to juggle a deluge of addictions and work while succumbing to another heart attack is an ecstatic feat of editing and movement. Leading up to the euphoric, hallucinatory finale in which Fosse, vis-à-vis his protagonist, articulates his own death through a shimmery, unforgettable musical number for the ages, this deeply personal Palme d’Or winner is the definitive unconventional biopic. – Jordan R.

Amour (Michael Haneke)

The death of a loved one is a staggering reminder of the concept of mortality; when that person is the one to whom you pledged “til death do us part” that reminder becomes more like a sick prank played by the universe. Michael Haneke, who never met a bleak premise he couldn’t imbue with humanity and gallows laughter, excels at exploring this existential mire as he observes a husband trying to care for and continue loving his declining wife. – Brian R.

Cléo from 5 to 7 (Agnès Varda)

The film that established Agnès Varda, Cléo from 5 to 7 marks both a prime example of French existentialism and a deconstruction of female objectification. Noted for its use of real-time narrative while its self-absorbed pop-star heroine awaits the results of a biopsy, Varda’s film plays not only with our perceptions of time but the female experience. As Cléo travels around Paris seeking solace from uninterested friends and sympathetic strangers, she learns to make peace with herself and gains autonomy over her own body and life—however long it may last. – Emmy P.

Death Becomes Her (Robert Zemeckis)

Mirrors are inescapable in Robert Zemeckis’ barbarous black comedy about the downsides of living (forever). They taunt their vain spectators––a rogue’s trio of Meryl Streep’s morally gluttonous seductress, Goldie Hawn’s vindictive femme fatale, and Bruce Willis’ dopey plastic surgeon caught in the middle. More a scab-flaying exhibition than a traditional morality play, Death Becomes Her cares less if the characters can look in the mirror than whether anyone else can tell they’re rotten inside and out. – Michael S.

Death in Venice (Luchino Visconti)

While Luchino Visconti’s filmography is mostly known for its grandeur and opulence, Death in Venice remains a curious oddity. Set in one of the most magical places on Earth depicted as hell, the Venice of this story is experiencing a cholera epidemic while visitor Gustav von Aschenbach (Dirk Bogarde) himself is declining with a heart disease. As his body deteriorates, leading to the inevitable finale, we see the embodiment of youth in his obsession with a boy named Tadzio. It’s an unsettling, uncomfortable experience filled with an evocative, palpable recognition of our temporary physical being. – Jordan R.

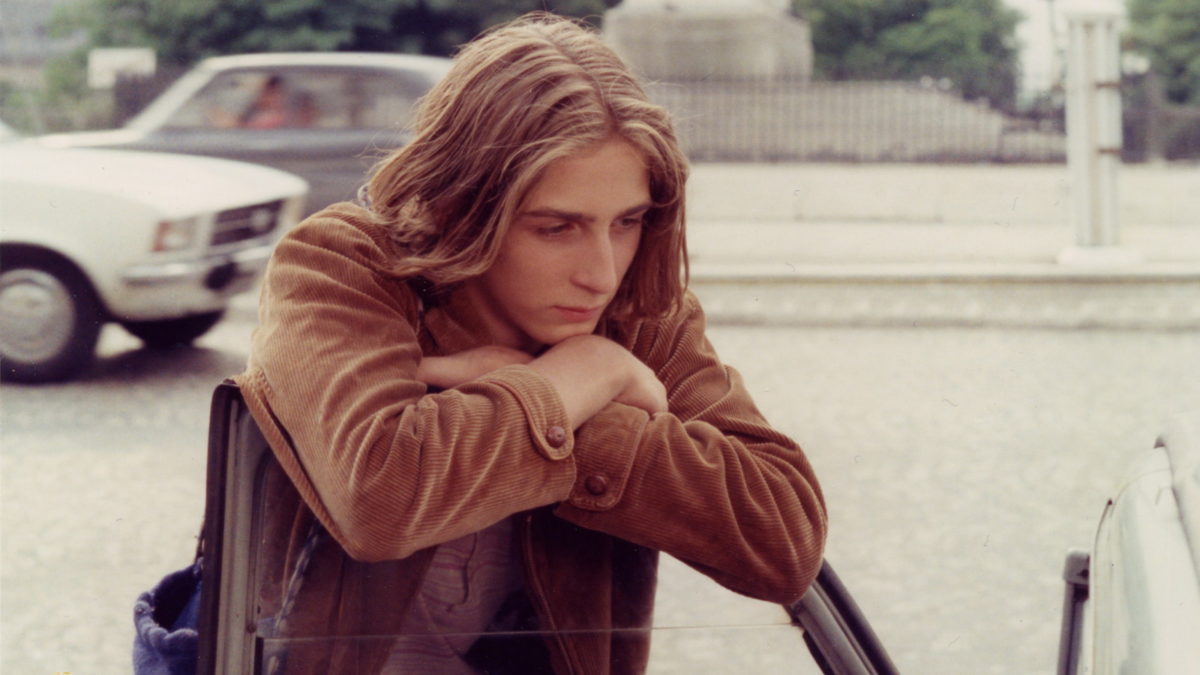

The Devil, Probably (Robert Bresson)

Robert Bresson’s condensing of elements to their bare essence to reveal a more poignant, affecting truth means the director is often keen to reach the logical conclusion of life itself: death. Apparent in Au hasard Balthazar, Mouchette, Diary of a Country Priest, and of course The Trial of Joan of Arc, this theme engulfs every frame of his penultimate film, The Devil, Probably. A key influence on a recent title also herein, this nihilistic portrait of a young soul in a suspended state of despair is evermore relatable decades later in dreading what the world has become. – Jordan R.

A Ghost Story (David Lowery)

The psychological weight of our certain death and the fact that life will go on long after we are departed is difficult to convey visually, but A Ghost Story is one of the most poignant films to ever grapple with this issue. It’s a singular feat of enthralling storytelling that I would say is going to leave a lasting impression centuries after everyone involved has passed away, but as Will Oldham (aka Bonnie “Prince” Billy) ponders in David Lowery’s micro-masterpiece, humanity will eventually perish. It’s not a comforting thought, to say the least, but A Ghost Story leaves enough room for the viewer to find peace in the reflection. – Jordan R.

Ikiru (Akira Kurosawa)

Ikiru, whose title translates to “to live,” is relentless. Its hero (Takashi Shimura) waddles between scenarios without any true family despite his job of anonymously serving others. He’d appear pathetic if he truly didn’t have a purpose, and, given his terminal illness, it’s likely he won’t discover what it is. That’s okay, though. Akira Kurosawa’s film embraces an almost secular life after death: a legacy, no matter how minute or unintended. Everyone lives. Some just live a little later than others; some a little later than themselves. – Matt C.

India Song (Marguerite Duras)

Operating on furtive glances the way cars in Mad Max need gasoline, India Song‘s protagonists wander a once-beautiful, now-dead mansion as reams of voiceover turn personal correspondence into hopeless prayer. Marguerite Duras’ work often plays like the transmission from a planet with entirely different conceptions of film form, and India Song marks a unity of idea and style rarely matched in cinema history. – Nick N.

The Irishman (Martin Scorsese)

The gangster movie must end with a righteous authority catching up to the criminals. But in Martin Scorsese’s The Irishman, no one ever apprehends Frank Sheeran (Robert De Niro). He faces far worse: a life in service of nothing, a death devoid of meaning. “It’s what it is” murmurs Joe Pesci’s Russell Bufalino––yet you can feel the film and the filmmaker fighting this absurd inevitability with unmatched urgency. If only we could keep the door open, even just a crack. – Jonah K.

The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger)

The Technicolor wonders of Powell & Pressburger have often explored mortality, notably in the masterful A Matter of Life and Death, but it’s The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp I return to again and again. In the span of nearly three hours, we witness a story of life and love which so eloquently and heartbreakingly captures the process of aging and longing that, by the finale, one may have a vivid reckoning of their own life’s journey before the end comes for us all. – Jordan R.

Melancholia (Lars von Trier)

Humanity is cursed with the knowledge of its certain death but blessed with coping mechanisms to bury that fact or find some level of peace with it. In Melancholia, writer/director Lars von Trier and actress Kirsten Dunst create a portrait of a woman for whom those mechanisms have been stripped away, leaving nothing but volatile—then deadening—depression. In the end, however, this blunt understanding provides the perspective needed to empathize with those for whom the knowledge is new and harrowing. – Brian R.

Never Let Me Go (Mark Romanek)

Towards the end of Never Let Me Go, someone exclaims in guttural agony at their lot in life. Suffice it to say that agony is fueled by the daunting task of three humans who must reckon with existence itself while navigating their love for one another. Director Mark Romanek and scribe Alex Garland encapsulate this within a high concept that’s built in highlighting the tragic, precious, and brief nature of life in the face of inescapable mortality. To divulge details would serve to undercut this film’s charms, but it’s a human trip (scored by the haunting work of composer Rachel Portman) that discovers the painful futility of life’s ultimate and insurmountable end. – Conor O.

Nocturama (Bertrand Bonello)

Of course our generation’s greatest apocalypse film concerns the hell of your own making. Bertrand Bonello’s thriller of a youthful terrorist-turned-consumer class harnesses its sublimity through immediate effect—elegant tracking shots, tight cuts, beautiful clothes, killer cues—but percolates for days, weeks, months, even years after its frightening vision of police state brings its hedonism to a close. And it summarizes She Dies Tomorrow‘s concerns in a single line of dialogue years before the fact: “I’m ready to die. After my death, carry out an autopsy to see if I was mentally deranged.” – Nick N.

The Seventh Seal (Ingmar Bergman)

Nearly the entire oeuvre of Ingmar Bergman could find a place on this list, and while specifically films like Cries & Whispers, Wild Strawberries, and Winter Light deal with death and mortality in deeply inquisitive ways, we’re spotlighting the film most explicitly interested in these themes. The Seventh Seal is perhaps his best-known feature for good reason. Set in a world of hopelessness and anguish––yet not without some signature touches of wit––this literal look at death explores the existential suffering that can only come with those given the gift of humanity. – Jordan R.

Solaris (Andrei Tarkovsky and Steven Soderbergh)

Between Andrei Tarkovsky’s magnificent 1972 film, Steven Soderbergh’s pensive 2002 masterpiece, and the brilliant Stanisław Lem novel on which both are based, there may not be a better-told story about the fragility of mortality. A man named Kelvin has an encounter with his dead wife while on a space station orbiting a planet called Solaris. Is it the reincarnation of his lost love? An extraterrestrial? His own regret manifested into something tangible? No matter the answer, the power of the journey is undeniable. The hardest part of living is being aware of death. Solaris, in all incarnations, is a distilled encapsulation of that feeling. – Dan M.

The Southerner (Jean Renoir)

The Southerner is an evergreen Americana story: a tenacious family sowing roots in an unlikely promised land. Jean Renoir’s 1945 masterpiece radiates charm even as the Tucker family contend with raging storms, droughts, and cruelly human neighbors. Each new problem feels insurmountable. But over and over, they pick themselves up. Extinguished and on the precipice by sundown; they still wake up ready for a new day whatever trial that may bring. – Michael S.

The Straight Story (David Lynch)

Intimacy is elusive in David Lynch’s 1999 feature—possibly even more than in his other works. Here, the camera is its own kindred spirit wading through the Midwest. The pace is languid, and virtually any given moment seems to look at itself as a faded memory. One could say the film’s arc is predestined, and perhaps it is, but it’s at terms with that, finding that rare intimacy that lets someone pass in peace. They don’t try to fill the air. They don’t have to talk. They just have to be there. – Matt C.

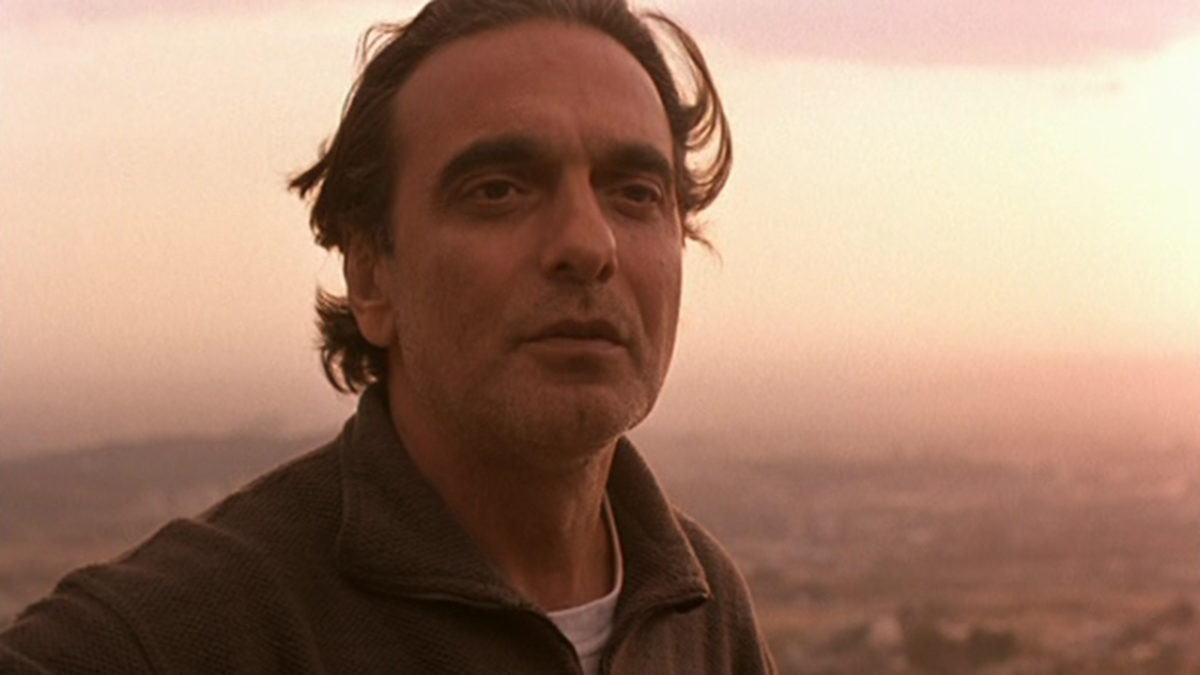

Taste of Cherry (Abbas Kiarostami)

Another director whose filmography speaks to mortality in more ways than one––the loneliness of 24 Frames, the aftermath of disaster in Life, and Nothing More…, awaiting death in The Wind Will Carry Us––Abbas Kiarostami’s greatest achievement in this regard is the newly, stunningly restored Taste of Cherry. Following a man who is attempting to commit suicide but needs to find someone who will bury his body, it’s a spare, poetic contemplation on the mind and the memory of our lives. Is the fourth-wall-breaking ending signify death or rebirth or something else entirely? Kiarostami is too brilliant an artist to give the easy answer; he’d rather have us still debating, years after he’s left this Earth. – Jordan R.

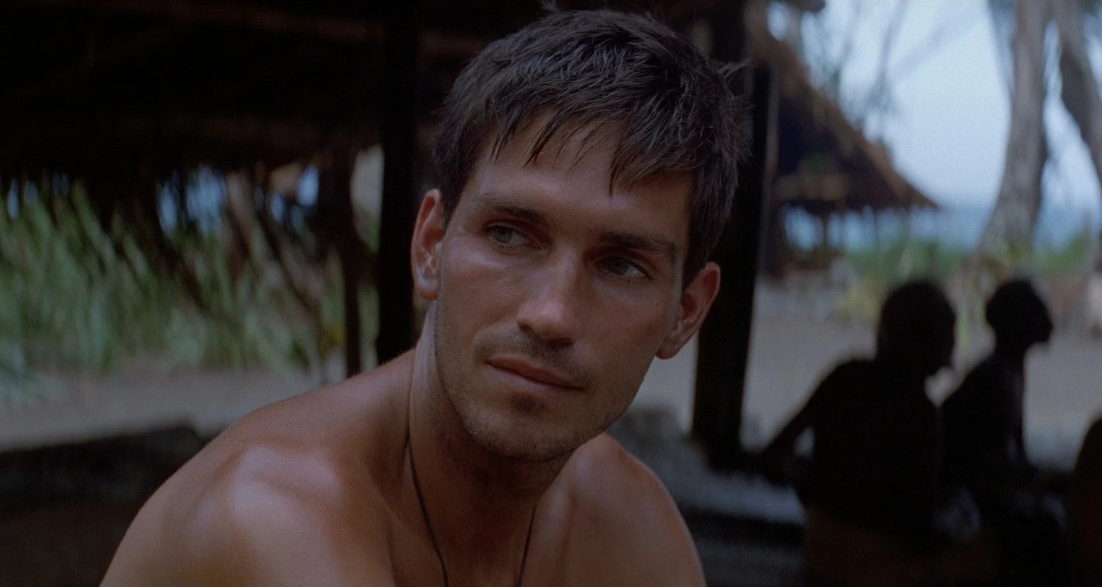

The Thin Red Line (Terrence Malick)

A war film has never been quite as death-haunted as Terrence Malick’s masterpiece. Most are indeed filled with the loss of human life, but the philosophical complexity and natural necessity of death has never been more integrally explored than here. Soldiers wrestle with their own moral guilt over the taking of life, dying men attempt to understand the point or meaning of their loss. In staring at the face of the Japanese dead, one soldier finds the common thread of humanity—mortality. All of this is couched in the discomfiting truth: war and death are natural to God’s creation. – Brian R.

World of Tomorrow (Don Hertzfeldt)

In the future, the wealthy can escape death by making a perfect clone of themselves. Into this clone they upload their consciousness, with only slightly deteriorating nuerophysical consequences. Animator Don Herzfeldt uses his formidable skills as a tragicomic philosopher to show us the way technology of the future battles the specter of death on both personal and global levels, and how the knowledge of mortality motivates and tortures man and machine alike. At the end of it all, this tour of the future from a many-times-removed clone comes back to single desire: to recall a memory of her mother from that first, natural-born version of herself. A reminder that life extension and technology may grant more time, but perhaps no more happiness. – Brian R.

Honorable Mentions

In attempting to consolidate favorites on such an expansive theme, it left a good amount on the table. While most horror films and war films could be considered to deal with mortality in some way, we also thought about Cristi Puiu’s Romanian New Wave landmark The Death of Mr. Lazarescu, the films of Hong Sangsoo (notably Hotel by the River), the heartbreaking Grave of the Fireflies, much of Krzysztof Kieślowski’s work, including A Short Film About Killing and The Double Life of Veronique, Hirokazu Kore-eda’s After Life, Jonathan Glazer’s Under the Skin, as well as Éric Rohmer’s The Green Ray.

In terms of American films, Joe Carnahan’s The Grey, Darren Aronofsky’s The Fountain, Todd Solondz’s Wiener-Dog, Albert Brooks’ Defending Your Life, Gus Van Sant’s Gerry, Mike Mills’ Beginners, Charlie Kaufman’s Synecdoche, NY, and a number of films by the Coens (notably A Serious Man and The Man Who Wasn’t There) all death with our lot in life in fascinating ways.