There are a multitude of reasons why any film may get unfairly overlooked. It could be a lack of marketing resources to provide a substantial push, or, due to a minuscule roll-out, not enough critics and audiences to be the champions it might require. It could simply be the timing of the picture itself; even in the world of studio filmmaking, some features take time to get their due. With an increasingly crowded marketplace, there are more reasons than ever that something might not find an audience and we’ve rounded up the releases that deserved more attention.

Note that all of the below films made less than $100K at the domestic box office at the time of posting–with a few exceptions for stellar Netflix/VOD films that went completely under the radar–and are, for the most part, left out of most year-end conversations. Sadly, many documentaries would qualify for this list, but we stuck strictly to narrative efforts; one can instead read our rundown of the top docs here.

Check out the list of 50 below, as presented in alphabetical order. A great deal of the below titles are also available to stream, so check out our feature here to catch up.

All Good (Eva Trobisch)

What immense health German cinema has found itself in lately. Since the turn of the decade, audiences of a certain ilk have grown accustomed to seeing names like Ade, Petzold, Grisebach, Schanelec, and Köhler show up on art-house and festival screens. We may soon need to add Eva Trobisch to that list. Yes, if All Good (Alles ist gut)–her snare drum taut and timely feature debut–is anything to go by, the East Berlin-born writer-director should provide that rich vein of deutsche Regisseure will its latest transfusion. – Rory O. (full review)

Age Out (A.J. Edwards)

The only thing worse than never getting your happy ending is having it within grasp and realizing you cannot accept it. To see salvation and turn around knowing it would be a lie is the type of heartbreaking choice we often have to make in order to keep on going. It’s the decision that separates man from monster: an admission of remorse, guilt, and regret. Our actions cause ripples that affect countless others we haven’t met yet or never will and while that truth allows some to sleep at night, the rest wonder what nightmares the collateral damage of their deeds endure as a result. You could say that the only thing separating those two groups is love. Knowing love is to understand its power and its pain. This idea is at the core of A.J. Edwards’ Age Out and his lead character Richie (Tye Sheridan). – Jared M. (full review)

Aniara (Pella Kågerman & Hugo Lilja)

The title shares its name with a city-size spacecraft ferrying humans from Earth to Mars in barely three weeks. It’s a routine trip that’s never run into problems with many passengers already having family on the red planet to greet them upon arrival. But there’s a first time for everything as a small field of debris forces Captain Chefone (Arvin Kananian) off course. Unfortunately a screw breaches their hull anyway, pushing their nuclear fuel supply to critical mass. Expelling it may save them for the moment, but without it they cannot steer. So despite having enough self-sustaining electricity and algae (for air and food), there’s no way to return onto their necessary trajectory. Either a celestial body interrupts their path to slingshot back or they simply drift forever. – Jared M. (full review)

Asako I & II (Ryusuke Hamaguchi)

Full-fledged, complicated but rapturous romance is relatively rare in cinema nowadays, and one of the very best examples is Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s Asako I & II, which uses its doubled lovers as a way to reflect back upon its main character, in all of her doubts and uncertainties. Deeply rooted in its present moment, yet prone to flights of fancy as transportive and unreal as any in contemporary filmmaking, the film delights as much as it aches, staying in close step with the turns caused by the whims of the self and the other, moving back and forth in rapture. – Ryan S.

By The Grace of God (François Ozon)

French director François Ozon has delivered one of the best films of his eclectic career with By the Grace of God, a drama whose seriousness and sincerity marks a tonal shift for a filmmaker typically famous for sexual and sensual provocation. Instead, this chronicle of a real-life grassroots campaign to out Catholic priests who committed and covered up of historic sexual abuse is unsensational and methodical, immaculately written through a script that radically tells three different stories that slide seamlessly together. – Ed F. (full review)

Buñuel in the Labyrinth of the Turtles (Salvador Simó)

Before surrealist legend Luis Buñuel found himself directing multiple films a year during the 1950s on the way to creating French classics like Belle de Jour and The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie in the 60s and 70s respectively, he became a persona non grata when it came to European benefactors thanks to his feature debut L’Age d’Or labeling him a heretic and almost getting his producer excommunicated by the Pope. With Salvador Dali at his side, the Un Chien Andalou filmmaker was dismissed as a provocateur nobody was willing to risk ruining their reputation over if he continued driving his own into the ground. Buñuel’s only chance of getting something new off the ground was his avant-garde artist friend Ramón Acín serendipitously winning the lottery… More than merely an anecdote, however, director Salvador Simó and co-writer Eligio R. Montero have drawn up their own film to delve into Buñuel’s mind as he struggled to escape the shadow of Dali, a wealthy upbringing sans paternal love, and the uncertainty of who he wanted to be as an artist – Jared M. (full review)

Chained for Life (Aaron Schimberg)

“Do you feel like the story is exploitative?” a journalist asks actress Mabel (Jess Weixler) about the new film she’s starring in, early into Aaron Schimberg’s brilliant second feature Chained for Life. In a meta-melodrama that constantly seesaws between fiction and reality, sprawling across a labyrinthine and multi-layered narrative that seamlessly jumps from one textual plane to another, I found myself wondering whether the question was in fact leveled at Schimberg’s own work. – Leonardo G. (full review)

CoinCoin and the Extra-Humans (Bruno Dumont)

CoinCoin, formerly known as Li’l Quinquin in Bruno Dumont’s film of the same title, is back in CoinCoin and the Extra-Humans (CoinCoin et les Z’inhumains). His name change, like the various physical and learning disabilities of the actors playing citizens of Dumont’s native Côte d’Opale, goes unexplained. It’s simply part of the story. If you’ve seen Li’l Quinquin, you know details like gendarme Van Der Weyden’s (Bernard Pruvost) Tourettes-twitching is constant, used for comedic effect, and as Dumont told the Guardian, “You have to decide whether or not you’re looking at something that disturbs you.” Like Li’l Quinquin, CoinCoin was made for Franco-German network Arte. Both were broken into four parts for television but screened as one film at festivals. CoinCoin stands alone in many ways, but to understand the last thirty, delightful minutes of the story, you’ll need to see Quinquin first. – Josh E. (full review)

Charlie Says (Mary Harron)

What if the Manson family murderers were also Charles Manson’s first victims? Charlie Says provides a window into the disturbed and tragic mindset of the three young women through the teachings of a young graduate student (Merritt Wever) as she helps the three girls Leslie ‘Lulu’ Van Houton (Hannah Murray), Patricia ‘Katie’ Krenwinkel (Sosie Bacon), and Susan ‘Sadie’ Atkins (Marianne Rendón) confront their harrowing experiences that lead them to the find solace into the arms of cultist Charles Manson (Matt Smith) who would groom them through sexual and emotional abuse into his devoted followers who would do anything for him, including murder. Mary Harron and her longtime collaborator Guinevere Turner provide an oft-ignored narrative that provides a fresh and feminist take into the minds of the three teenage girls, where their tragic backgrounds made them ideal prey for his cult. – Margaret R.

Daughter of Mine (Laura Bispuri)

Laura Bispuri’s follow-up to her captivating transgender-themed debut Sworn Virgin is a wrenching, heartfelt drama with an unfussy social commentary that again seeks a new definition of womanhood. Daughter of Mine, led by a trio of female actors–Valeria Golino and Alba Rorwacher, and an equally headstrong first-timer, Sara Casu–contemplates the nature of motherhood in a variety of forms: adoption and the absence of a birth mother, the lack of father figures, and even the effect of an exclusively female family unit. Why is society obsessed with balance in nuclear families about gender–mother and father–rather than in more complex sensibilities? – Ed F. (full review)

The Death of Dick Long (Daniel Scheinert)

After carving out a name for himself with Swiss Army Man, co-writer and co-director Daniel Scheinert branched out on his own for his next feature, The Death of Dick Long. Stranger and darker than Swiss Army Man, this is a film steeped in sadness and anxiety, despite, or perhaps, in part, because of its close relationship to comedy. The result is a film that asks one to follow characters who are both reprehensible and highly relatable in (somewhat) equal measure, with the narrative around them weaving between buddy comedy, bumbling police procedural, and severe familial breakdown. Between Hinder needle drops and vape clouds, Scheinert carries the whole thing with emotional intuition, visual ingenuity, and a heavy trust in his actors, none of whom are afraid to get weird. And yes, things get weird. – Mike M.

Domino (Brian De Palma)

The latest from Brian De Palma hits film culture not unlike a moody son trudging to their graduation party at a parent’s behest, a master of big-screen compositions relegated to VOD for those who bother plunking down. That tussle between pedigree of talent and nature of distribution foretells the chaos within: at one moment lit like a Home Depot model living room–a fault I’m more willing to chalk up to incomplete post-production, less likely to blame on Pedro Almodóvar’s longtime DP José Luis Alcaine–the next photographed and cut as if an old pros’ sumptuous fuck-you to pre-vis-heavy and coverage-obsessed action-filmmaking climate, the next maybe just an assembly of whatever master shots the team could scrounge together during those 30 production days. To these eyes it’s a chaotic joy; nearly malicious, deeply serious about the wounds of contemporary terrorism, and smart enough to pull off a mocking of the circumstances around those fighting it. – Nick N. (full review)

Dragged Across Concrete (S. Craig Zahler)

Anyone transfixed by the hyper-stylized meathead triumph of blood and violence of Brawl in Cell 99 should be warned. Dragged Across Concrete, S. Craig Zahler’s third feature, is comparatively much tamer than his 2017 prison drama. But where the new entry lacks in bloodshed and bone-splintering violence, it still confirms Zahler’s penchant for complicated characters, and conjures up a bad cops action movie which, despite blips in tension and a second half far superior to the first, crystallizes Zahler’s as a key name to watch for lovers of the genre. – Leonardo G. (full review)

An Elephant Sitting Still (Hu Bo)

Nearly two years after the suicide of novelist-turned-filmmaker Hu Bo, his first and, sadly, final feature, An Elephant Sitting Still, is at last reached our shores with a release earlier this year. Although relatively well-known amongst his generation for his impassioned writing, Hu never had a chance to develop a following overseas outside of tight-knit arthouse film communities. Woefully fitting, considering Elephant concerns itself with those underprivileged, marginalized and largely forgotten in the face of Mainland China’s rapid modernization. Set in the northern border city of Manzhouli, three generations of China are represented across the four main characters, all bound together by their ambition, conscious or not, to be free from the tragic, cyclical rhythms of their demoralizing lower-class existence—painstakingly conveyed through staggering long takes over the course of the film’s near four-hour runtime. Hu Bo’s legacy will live on through this monolithic debut: a wistful paean for the destitute souls of contemporary China; lost but not forgotten. – Kyle P.

End of the Century (Lucio Castro)

Director Lucio Castro’s ravishing debut film gives a twist to the tradition of one-day-romance from films like Before Sunrise and Weekend. At first glance the instant attraction between strangers Javi (Ramon Pujol) and Ocho (Juan Barberini) seems to follow in line with what other films in the subgenre have done before. But a twist that could take it into psychological suspense territory, instead transforms it into a soulful meditation on the myth of “the one” and how much pressure we put on ourselves to fit the mold of romance created by cinema. – Jose S.

Fast Color (Julia Hart)

Set in a dystopian present, Julia Hart’s sci-fi banger follows three generations of black women as they try to navigate and harness special powers that have been handed down through their family for generations. Gugu Mbatha-Raw leads a brilliant ensemble as the conflicted centerpiece, the prodigal lynchpin of a clandestine clan of activists whose mere existence threatens the authoritarian powers that be. This beautifully told genre film reveals how much time Hollywood has wasted creating stories in service of special effects, and not the other way around. Move over Marvel, this is what a real superhero movie looks like. – Glenn H.

Feast of the Epiphany (Michael Koresky, Jeff Reichert & Farihah Zaman)

What most strikes in Feast of the Epiphany is a sense of conviction and fidelity, a willingness to document things as they are: unvarnished and imperfect. Though the two halves only connect back for a fleeting instant at the very end, and otherwise represent entirely different visions of what a specific place can contain, neither is “incomplete” in and of itself; both are allowed the proper time to linger and settle. Koresky, Reichert, and Zaman’s daring is thus no mere gambit: it registers less as a simple bait-and-switch and much more as a conscious, courageous attempt to recalibrate notions of society and belonging. – Ryan S. (full review)

La Flor (Mariano Llinás)

The fundamental details surrounding La Flor — its fourteen-hour running time, its ten-year production, its appropriately devilish six-part structure — already have it predestined for cult status, and yet Mariano Llinás’s mammoth effort both fulfill and far exceed any preconceptions. An extraordinary ode to forgotten genres, a sincere and open-hearted love letter to its four central actresses, who turn in some of the most astonishing performances in recent memory: what is perhaps most overwhelming about La Flor is that it manages to contain infinite worlds of pleasure, surprise, and glory, while paying tribute to the possibilities of cinema, storytelling, and human creativity. – Ryan S.

A Land Imagined (Yeo Siew Hua)

Cooked with a broth of a few too many ideas, A Land Imagined is a so-close-to-being-great Singapore neo-noir that does all the right things, but simply does too many of them in its snappy 95-minute running time. Only his second feature, Singapore-born writer-director Yeo Siew Hua was awarded the Gold Leopard in Locarno for his enigmatic new film. His story tells of a detective who arrives on a land reclamation site to investigate how and why one of the workers disappeared. What Yeo presents is remarkable for its style and ambition but also for its scattered folly, a world of Lynchian dreams and techno-surrealism that somehow echoes both Chinatown and Wong Kar-wai. It’s also a tale buckling at the knees under all that symbolism and with at least one too many loose ends left dangling. – Rory O. (full review)

Leto (Kirill Serebrennikov)

At a time when freedom of expression titters on the brink in Vladimir Putin’s Russia, there’s something thrillingly contemporary about Kirill Serebrennikov’s Soviet-set musical drama. Early 1980s St. Petersburg proves a breeding ground of underground music as rebellion, however tacit, emerges in home-grown rock and punk. Leto’s melancholic ode to rough-and-ready counterculture proves ever more relevant as Serebrennikov, himself an avant-garde theater director, remains under house arrest in Moscow. – Ed F. (full review)

Light From Light (Paul Harrill)

Single mother Sheila (Marin Ireland) is a car rental saleswoman by day and paranormal investigator by night. Raising her teenage son, Owen (Josh Wiggins), however, is a full-time job. Or, at least, it was and she preferred it that way. Now their relationship is strained as both face the likelihood of extended separation due to Owen being college-bound and becoming increasingly independent. A job opportunity to study a widower’s supposedly haunted abode could give them the chance they need to reconnect or might only make matters worse. Light from Light is an understated ghost story that forgoes the supernatural in favor of examining how such pursuits can reflect the psychic and emotional wounds left behind by the deceased. Furthermore, it’s about carrying on as the pang of loss lingers long after grief has subsided without the film ever resorting to amateur psychoanalysis or storytelling contrivances. Instead, Paul Harrill’s sensitive direction allows the characters to organically come to their own conclusions, bolstered by outstanding performances from Marin Ireland and, unexpectedly, Jim Gaffigan as the widower, Richard. – Kyle P.

Luz (Tilman Singer)

It’s been years since a demonic entity has seen the woman it loves—she who conjured it to the surface before being driven out from the place in which she did. Tonight was a chance reunion wherein familiarity was quickly replaced by violence before a yet-unseen escape sees both parties going their separate ways. The woman stumbles towards a virtually deserted police station while the force of evil seeks out someone else who might be able to help it confront her within an environment it can control. So as Luz Carrara (Luana Velis) blasphemes God in Spanish via a distorted prayer to the two German detectives assigned to her, Nora Vanderkurt (Julia Riedler) solicits Dr. Rossini (Jan Bluthardt) at a bar with a tale of her girlfriend’s woe. – Jared M. (full review)

Genesis (Philippe Lesage)

It’s been nearly two years since that luminous mid-August morning when Philippe Lesage’s Genesis premiered in Locarno, and I find myself returning to it still. I don’t expect this to change anytime soon. A singular, engrossing coming-of-age tale, Genesis injects plenty of energy and fresh air into a saturated genre, not least because of its bold and confounding formal choices, twists and ellipses. How else would you describe a film that suddenly chooses to abandon its main plot line two hours in, to revisit characters from another film altogether? (Genesis’s last act exhumes Les Démons, a film Lesage made in 2015–and the shift, for some miraculous reason, just clicks). It’s a maddening and perturbing ride, lulling to the melancholic beat of Outside by Montreal band TOPS. That it feels impossible to pinpoint is a testament to its endless charms. – Leo G.

Grass (Hong Sang-soo)

Barely running over an hour, what might seem to be one of Hong Sang-soo’s most modest and stripped-down efforts—in an oeuvre gloriously full of them—reveals itself to be perhaps his most dizzyingly complex. Grass is Hong at his most Rivettian, using strange repetitions of details in stories, odd narrative detours, joining of image and sound unlike any in his filmography, and above all Kim Min-hee’s attentive writer to explore notions of storytelling, death, and connection with a rare precision and mystery. Somehow, it’s possibly one of Hong’s greatest and most ambitious films. – Ryan S.

Greener Grass (Jocelyn DeBoer and Dawn Luebbe)

Somewhere in a strange corner of suburbia lives two married couples: Nick (Beck Bennett) and Jill (Jocelyn DeBoer) & Lisa (Dawn Luebbe) and Dennis (Neil Casey). While the two women are constantly competing with one another, practicing a kooky version of passive-aggression, the men bop around like idiots. At one point early on, the two pairs make out for an extended period of time only to realize they’re kissing the wrong person. In another scene, a baby is gifted from one mother to another, just because. – Dan M. (full review)

Hotel by the River (Hong Sang-soo)

Not that Hong Sang-soo ever makes a bad film, or seems barely capable of doing so, but if I found myself more smitten with his usual tricks—the granular conversations in a locked two-shot, the bright tones of its black-and-white palette, the blink-and-you’ll-miss futzes with structure, Kim Min-hee photographed with affection one only reserves for somebody they love—it’s because this is maybe the first since Hill of Freedom (a best-of-decade-level work) that finds new ways to traverse his well-worn emotional landscape. – Nick N.

In Fabric (Peter Strickland)

The horror and comedy genres rarely coalesce as well as they do in Peter Strickland’s chronicle of a possessed dress, its tragic lineage of owners, and the cult department store that erotically imbues it with powers. In Fabric effectively channels the absurdity of its premise towards a critique of late-stage capitalism, invoking the bright red hue of its haunted garment or the futility of its working-class protagonists in ways that manage to be simultaneously comedic and ominous. Although historically indebted to Giallo influences, Strickland’s latest work feels new precisely because of how it subverts expectations. A hypnotic score by synth-pop duo Cavern of Anti-Matter paired with anachronistic setting and retro imaging wrings tension through both its association with predecessors and reflection of real-world alienation. Playful collage montages of fashion clippings feel like something out of “Society of the Spectacle,” turning sinister before our eyes. – Jason O.

“I Do Not Care If We Go Down in History as Barbarians” (Radu Jude)

Inverted commas withstanding, “I Do Not Care If We Go Down in History as Barbarians” seems like an awfully long and pretentious thing to call a film. Indeed, it might even suggest that something long and pretentious will be awaiting any viewer of Radu Jude’s latest creation but thankfully, in this case at very least, only one of those adjectives is true. At 140 minutes, Barbarians (as it will be referred to from here) is indeed rather long, especially when considering that one could easily describe it as a drawn-out dialectic on the responsibility of nations to confront whatever atrocities their government and populous committed in the past. So how on earth is Barbarians so funny and compelling? Well, one reason might be that it’s a movie by Radu Jude, a Romanian New Wave filmmaker who has managed to operate just outside the main spotlight of his gilded colleagues, occasionally departing from their stark contemporary realism while always sharing in their brand of gallows humor. – Rory O. (full review)

In My Room (Ulrich Köhler)

At what point do vaguely-related surface movements form into something resembling a wave? The idea of a so-called “Berlin School” has been doing the rounds for quite a while. However, the creative output of that group of filmmakers in the last few years has been nothing short of astonishing. Christian Petzold led the way with Barbara (2012) and Phoenix (2014) but nothing could have prepared us for Maren Ade’s Toni Erdmann rocking Cannes or Valeska Grisebach’s Western doing the same last year. Petzold’s Transit divided audiences (we thought it was great) in Berlin in February and now we encounter this strange, intimate, little science-fiction film. – Rory O. (full review)

The Image Book (Jean-Luc Godard)

While Jean-Luc Godard’s canonized ‘60s films may garner ample discussion in film studies classrooms, such a myopic understanding of his entire oeuvre only represents a single decade of innovation in a body of work that regularly challenges the status quo. From the radical Dziga Vertov era and its political discourses to the Anne-Marie Mielville Son-Image collaborations to the more recent video essay work, each of his films after the New Wave signify a fundamental Godardian instinct to not only espouse complex dialectics but also to reinvent the expression of those themes. His latest work, The Image Book, is no different, retaliating over this modern era of neutered political cinema with an energetic history lesson about the medium’s legacy in (mis)representing the atrocities of the 19th and 20th centuries. Like many of his art-statements, the film is overlooked because of the ways in which it challenges the spectator with overwhelming formal reconfiguration and brash commentary; like many of this characterization, it readily deserves a viewing–if not for the ideals at its core, then at least for the very necessary reminder that cinema can be more than its limitations. – Jason O.

Knife + Heart (Yann Gonzalez)

There is a movie within the movie Knife + Heart and it boasts the slightly euphemistic title of Homocidal (although I prefer the working title: Anal Fury). It is, in fact, being filmed as we watch, along with a number of other similarly lewd movies. Homocidal is the latest production of Far West Films, a fictional queer softcore porn studio that acts as the focus of Knife + Heart, a delightfully icky horror movie seeped in beautiful Giallo homage that is the second feature of Niçoise polymath Yann Gonzalez (who you might know as one half of M83). – Rory O. (full review)

Knives and Skin (Jennifer Reeder)

An official selection at Berlinale, Tribeca, Fantastic, Fantasia, and more festivals this year, Jared Mobarak said in our glowing review, “It’s thus a magical thing when Reeder lets them open their wings and fly. Sometimes it’s a cutting verbal barb or a devastating blow to the head with a folding chair, but it’s always this profound cathartic release… That she so effortlessly moves from the severity of such sequences to the restrained humor of others can’t be undersold since that dynamic is crucial for the film’s intentional artificiality to resonate as wholly authentic.”

The Load (Ognjen Glavonić)

Tracer fire perforates the horizon multiple times in Ognjen Glavonic’s slow burning character study, an eerie reference point to armed conflict that is seemingly omniscient in Serbia. The threat of NATO bombings and sectarian violence has become part of daily life for citizens like Vlada, a struggling truck driver who takes a long haul job carrying shady cargo in order to provide for his family. His cross-country odyssey through an eerily quiet warzone helps realize the stagnating madness of war. It is within this ecosystem of helplessness and indifference that genocide flourishes. – Glenn H.

Manta Ray (Phuttiphong Aroonpheng)

Halfway through Phuttiphong Aroonpheng’s hypnotic feature debut, Manta Ray, two men put up Christmas lights around an unadorned riverside shack. They’ve known each other for a while, but seldom speak: one (Wanlop Rungkumjad) is an unnamed Thai fisherman with dyed blonde hair; the other (Aphisit Hama) is a mute man whom the fisherman has found agonizing in a remote stretch of mangroves by the border with Myanmar, and has taken home to look after. The lights are to serve as decoration for a party the two are throwing that same night, but the sun is still high on the horizon; smiling ecstatically at the makeshift disco, the fisherman suggests the two should nap to make the day go by faster. And so they do. – Leonardo G. (full review)

One Cut of the Dead (Shinichiro Ueda)

In this era of insufferable “elevated” horror, Shinichiro Ueda’s fleet-footed, sharp-toothed genre meditation takes a shockingly heartfelt and emotionally resonant approach to celebrating the rigors of collaborative (and sacrificial) filmmaking. From the rough and tumble chaos of the first act to the meta sublimity of its final moments, this is a shapeshifting work of behind-the-scenes mythmaking that commemorates the overlap between artistic ambition and messy, pragmatic execution. – Glenn H.

Our Time (Carlos Reygadas)

Carlos Reygadas’ films are often semi-autobiographical, typically exploring intimacy and suffering through metaphysical and philosophical lenses that are by turns cosmic and illusory. His latest film, Our Time, is no different. Truthfully, it might be his most personal film to date, painfully honest in its portrayal of a disintegrating marriage, with husband and wife played by Reygadas himself and his wife, Natalia López. Although the film recalls the marital infidelity of Reygadas’ Silent Light, paralleling the cosmos and seemingly boundless Mexican skyline with extramarital affairs and phlegmatic interiorities, Our Time pushes the envelope with its metatextual angle. Some have likened the film to couple’s therapy, with implicit disdain for the self-indulgence such a premise can have. However, this comes across as a critical misreading. The film is not a form of justification or apologia; neither vindication nor denunciation. Our Time is a personal testament, not to the character of Reygadas or López, but rather the complexities of matrimony when love breaks down beyond spiritual repair. – Kyle P.

Pasolini (Abel Ferrara)

Arriving in U.S. theaters five years after its Venice International Film Festival premiere, Abel Ferrara’s unapologetic and frank exploration of the late filmmaker and scholar Pier Paolo Pasolini’s last days features a sublime performance by William Dafoe. The nature of the film is more explicit than a polite Hollywood biopic, as an unhinged auteur explores the takes on the legacy of another unhinged auteur as he completed his infamous Salo, or the 120 Days of Sodom. Beautifully lensed, the film is ripe with contradictions creating a portrait of an academic, a playboy, and a momma’s boy employed effortlessly by Dafoe. – John F

The Plagiarists (Peter Parlow)

It’s the single funniest “twist”—quote marks mine, but also, maybe, the movie’s as well—of anything you’ve seen this decade until its troubling implications diffuse forward and backward through everything else the movie has done, and maybe its second half is a pale imitation of the first and maybe a but-that’s-exactly-the-point justification is tired, but: this movie posits that everything we verbalize as original thought is a recapitulation of someone else’s idea, and if you’ll ever be able to fully shake that thought, you have my envy. – Nick N.

Queen of Hearts (May el-Toukhy)

When it comes to sex, things can get real complicated real fast. While the act itself may be dictated by the most primal of instincts, questions of morality, legality, gender, power, not to mention that funny little thing called feelings often ensure that no bodily liquids are exchanged without consequences. In Danish writer/director May el-Toukhy’s gripping, thought-provoking erotic drama Queen of Hearts, problematic sex happens at an unlikely place. – Zhuo-Ning Su (full review)

Ray & Liz (Richard Billingham)

If there is an image to best introduce audiences to the grimy cinematic world of Ray & Liz–the remarkable debut feature of Turner prize-nominated visual artist Richard Billingham–it might be, fittingly, the very first one to hit the screen: that of a cracked, burnt-out light bulb filmed dangling beneath a nicotine-stained ceiling. Billingham has spent much of his career as an artist documenting and, in his short films, dramatizing the lives of his father Raymond (a chronic alcoholic played here by Patrick Romer and, as a younger man, by Justin Salinger ) and mother Elizabeth (Deirdre Kelly and–best of all–Ella Smith) and Ray & Liz could be viewed as a culmination of that work. It’s an immersive poetic-realist dive into the artist’s fractured memories of his parents during the time he spent growing up in Birmingham in the ‘70s and ‘80s. – Rory O. (full review)

Relaxer (Joel Potrykus)

Typically, independent filmmakers scale up as they continue to make films, but in his fourth outing Michigan madman auteur Joel Potrykus unapologetically scales down to the corner of an apartment where we find out hero Abby (Joshua Burge) subject to a series of challenges by his brother Cam (David Dastmalchian) that involve projectile vomiting, raw sewage, and the end of the days, all while under the watchful eye of a Sony handicam. It’s not surprising the film wasn’t a box office smash; Relaxer is not for everyone, but if you have the patience to let it wash over you, expect a hilarious, uncompromising, and even thrilling experience. – John F

Sorry Angel (Christophe Honoré)

We can assume that Christophe Honoré’s 10th big-screen feature as director might trigger some viewers’ short-term memories — and perhaps apprehension, too. Considering the year that cinema has had, certain things inevitably spring to mind at the thought of a love story between an older, cosmopolitan, more worldly, more intellectual man and an intelligent, albeit impressionable younger guy; as does, in another way, the idea of an HIV story set in early-90s Paris. Some mistaken folk might even rush to call Sorry Angel “this year’s Call Me by Your Name” (you’d have to have been living under a rock to call it this year’s BPM), but it is a far more melancholic and drab piece than Luca Guadagnino’s all-conquering (well, mostly conquering) hit. – Rory O. (full review)

Suburban Birds (Qiu Sheng)

Something is causing the ground to shift underneath a new Chinese suburb in writer-director Qiu Sheng’s intriguing, adept debut feature. High-rise towers are listing to the side, and residents are being evacuated. As Suburban Birds begins, a team of engineers is on-site to investigate the cause—ideally quickly, without disrupting the planned subway tunneling, so that this little part of China’s development boom can proceed. Make way for tomorrow! It’s left to Qiu to survey the restless earth around the foundations of the future, via a subtle structural gambit that marks his voice as one worth listening to. – Mark A. (full review)

Styx (Wolfgang Fischer)

Formally precise but more free-flowing in its rhetorical curiosity, Wolfgang Fischer’s fleet, process-heavy drama presents a moral dilemma with an easy “right” answer that’s tethered to guaranteed consequences. A one-woman-show, the excellent Susanne Wolff ebbs and flows between her altruistic instincts and her knowledge of the laws of the country until the film is longer a personal illustration of character as much as a country’s responsibility to their people and the defined limits of their empathy. – Michael S.

The Third Wife (Ash Mayfair)

It’s 19th century Vietnam and fourteen-year-old May (Nguyen Phuong Tra My) has just been married to a wealthy landowner named Hung (Long Le Vu). She wears a genuine smile on her face, this next chapter in life as hopeful as it is scary. She has two other women to help steer her through womanhood, motherhood, and sexual pleasure (Nu Yên-Khê Tran’s first wife Ha and Mai Thu Huong Maya’s second wife Xuan) and a future of comfort awaiting her with but one goal: bearing a son. A bloody sheet is displayed to represent consummation; a growing belly to prove no time was wasted for conception. And as the days progress with less and less to do thanks to servants, May’s eyes and mind begin to gradually wander. – Jared M. (full review)

Too Late to Die Young (Dominga Sotomayor)

Based in part on Dominga Sotomayor’s own childhood, Too Late to Die Young distinguishes itself from rote coming-of-age narratives in its clarity of vision and specificity, detailing the run-up to New Year’s Eve in a secluded Chilean artists’ commune and focusing as much on the surrounding hopes and dull realities of the community as on its central character. This, coupled with a fine eye for Academy ratio direction, gives a clarifying focus on atmosphere and quotidian rhythm that feels vital for the film, taking these people and their milieu on their own terms in compassionate fashion. – Ryan S.

Two Plains & a Fancy (Lev Kalman and Whitney Horn)

Co-directors Lev Kalman and Whitney Horn make films that defy genre conventions, and we’re all the better for it. This off-kilter “Spa Western” in which three strangers who rarely stop gabbing travel around frontier Colorado searching for particular hot springs is by far their most ambitious movie to date. Shot on location using a skeleton crew, it’s got the feel of a rustic campfire sleepover under the stars that could diverge into surrealist geothermic disaster at any moment. American cinema rarely takes viewers off the beaten path in such ways, but that’s exactly what happens in this genuinely singular indie. – Glenn H.

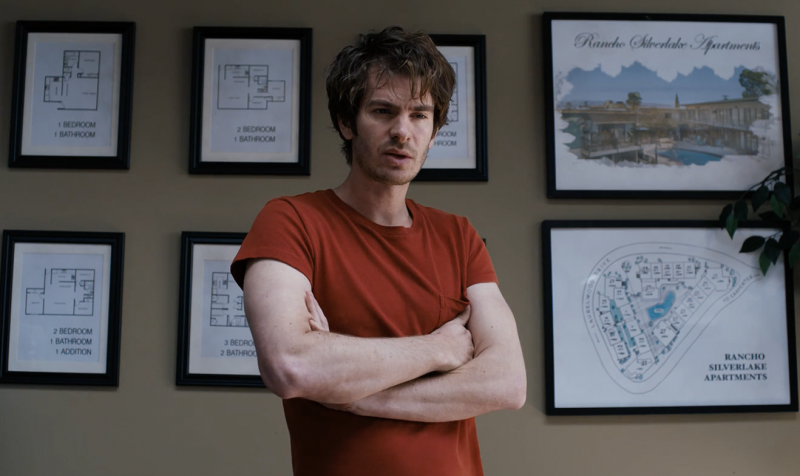

Under the Silver Lake (David Robert Mitchell)

David Robert Mitchell is a nostalgic. His debut feature, The Myth of the American Sleepover, paid tribute to such teenage dramas as American Graffiti and the work of John Hughes. Its follow-up, the terrific It Follows, ranks amongst the smartest and most effective specimens in John Carpenter’s vast and variegated suburban horror legacy. Mitchell has now tried his hand at an L.A. noir with Under the Silver Lake, which owes as big a debt to The Long Goodbye, Mulholland Drive, and Inherent Vice (to mention but three of the most conspicuous referents) as it does Thomas Pynchon’s labyrinthine, paranoia-laden narratives. – Giovanni M.C. (full review)

The Wandering Soap Opera (Raúl Ruiz)

Tackling this posthumous release from renowned experimental filmmaker Raúl Ruiz with limited knowledge of telenovelas and the subtleties of early ‘90s Chilean politics is like trying to eat a rough cut of meat with a butter knife: there’s every chance it’s delicious — it might even be good for you — but it remains difficult to pin down. Indeed, there is a lot going on in The Wandering Soap Opera (La telenovela errante), a previously unfinished project that has been completed for release by Ruiz’s widow and long time editor Valeria Sarmiento. – Rory O. (full review)

The Wild Pear Tree (Nuri Bilge Ceylan)

Perhaps it’s the film’s daunting 190-minute runtime that proved too intimidating and inaccessible for audiences to embrace. It’s a shame, because The Wild Pear Tree is not only one of the best films of the year, but easily of the decade. A soulful portrait of existential alienation set against a panoramic backdrop of Turkey’s countryside and coastal landscapes that are alternately majestic and melancholy, Ceylan’s masterpiece harnesses the ennui of modern Turkey to reflect on the world at large; art, metaphysics, religion, spirituality, death, morality and how one’s connection to animals and nature is the ultimate salve against life’s pitiless and materialistic absurdity. The Wild Pear Tree is about how we choose to define our place in society, as Ceylan subtly pushes us to rethink our narrow notions of success and failure. With this film, he has fashioned a gentle and poignant odyssey—for his protagonist and for us viewers—towards inner peace, one that requires us to transcend the familial rifts, parental legacies and generational chasms that might stand in our way. To that end, The Wild Pear Tree’s emotional gut-punch lies in its understanding that it’s the parent with whom we share the most fraught relationship—who we most resent and take for granted—that understands us to our core, and with whom lies the most sacred bond, tender love, and spiritual empathy—and how achieving this humbling revelation, while emotionally overwhelming, is the ultimate sign of personal growth. Ultimately, the film suggests that perhaps the truest form of success is the ability to navigate life and be a productive member of society within a contrarian nook we carve for ourselves. – Demi K.