Following our top 50 films of 2019, we’re sharing personal top 10 lists from our contributors. Check out the latest below and see our complete year-end coverage here.

If this past decade’s trajectory of film consumption continues, the future of film culture seems extremely promising. Despite the continued homogenization of certain studio slates dominating the mainstream box office, a rejuvenated political consciousness and the proliferation of streaming services has breathed a second life into those kinds of previously unavailable (unmarketable) films, now accessible to a broader public. Arthouse films are contended in wider circles; mid-budget filmmaking is reappearing from distinguished directors that could never quite draw the theater audiences they expected. Ticket sales may have steadily decreased, but the surge in options has integrated films more readily with the general social experience!

It is with this comfort in eventual exposure that I list some of my favorite films that premiered this year at film festivals that will not be officially released until 2020. Whereas in years prior, they would remain invisible outside of small crowds in major cities, perhaps now they will get the attention they deserve. Five that stand out are: Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s globe-trotting alienation piece To the Ends of the Earth, Kelly Reichardt’s tale of budding capitalism and friendship on the American frontier First Cow, Heinz Emigholz’s architecture documentary Years of Construction, Pablo Larraín’s lively dance melodrama Ema, and Pedro Costa’s somber Vitalina Varela.

This year, I found myself less interested in those films with one-sided agendas that derive their social significance and widespread discourses from their reiteration of urgent issues. Despite some of their more formal successes, I feel as if they promote aspects of echo-chamber politics that hardly impress new perspectives or experiences onto their audience. As such, most of my favorite films this year fall into the category of “termite art,” restoring the lost art of dialectics by forming balanced arguments surrounding more latent subjects. These often disguise themselves in the form of entertaining genre films, but nevertheless contain layered arguments that challenge binary representations of more complicated debates. Many are also significantly strengthened by the ways in which their directors took advantage of new technology or reoriented old technology to create altered models of spectatorship.

My honorable mentions also follow this trend and are still worthy of note, but narrowly miss out on being in my top 10. The Wandering Soap Opera comedically blurs the line between Chilean reality and soap opera form with a series of vignettes, originally filmed in 1990 by the legendary arthouse director Raúl Ruiz and stitched together in the years following his death in 2011 by wife and frequent collaborator Valeria Sarmiento. When I Get Home, operating in the intersections of the performance art, experimental film, and music video genres, is an early pioneer of the visual album and highlights a promising direction for interdisciplinary art. Sam Mendes’ 1917 uses its one-take gimmick well and features an incredible Tarkovsky-inspired aesthetic from Roger Deakins–one of those rare visceral movies that overwhelm thinking with an immersive and nonstop barrage of sense-stimuli. M. Night Shyamalan’s Glass grounds the all-too-common superhero genre with real emotions untampered with by studios, setting itself apart from all those identical other works by highlighting institutional failings and the effects of trauma in a more authentic manner. Pain & Glory is a bittersweet love letter to cinema from Pedro Almodóvar, one of cinema’s most prolific romantics.

Here’s the rest!

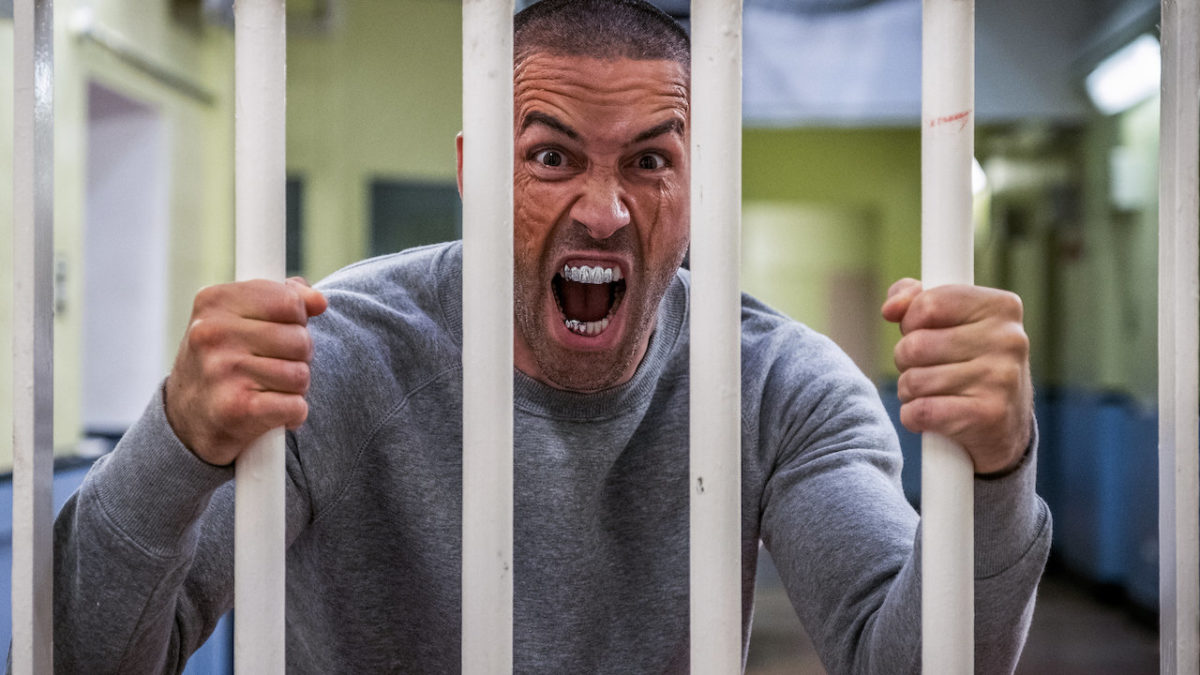

10. Avengement (Jesse V. Johnson)

Former stunt coordinator Jesse Johnson and muse Scott Adkins’ fourth collaboration is the first of their work to not rely on comedy and their best film yet. This is pure DTV action that packages the unfathomably charismatic Adkins–who masterfully transforms into the role–with respectfully rhythmic and brutal fight choreography and just enough of a political consciousness in a sub-90-minute long thriller that never overstays its welcome. The two continue to highlight the often ignored straight to VOD film genre as the best site for genuine, visceral action. That the emotional beats manage to hit is but further testament to Adkins and Johnson’s unexpected growth as leading man and director, respectively.

9. The Beach Bum (Harmony Korine)

The Cult of Moondog offers vicarious liberation from materialistic struggles and reprioritizes the need for spiritual nourishment and wanderlust! Matthew McConaughey is at his most McConaughey here, and performances from him, Isla Fisher, Zac Efron, Snoop Dogg, and Martin Lawrence are some of the most unique and hilarious character work of recent memory. In classic Harmony Korine fashion, its off-kilter unpredictability is often offset by its genuinely comforting, transcendently utopian humanism.

8. Ash Is Purest White (Jia Zhangke)

Jia Zhangke’s latest period triptych corrects a lot of the less satisfying elements of predecessor Mountains May Depart. In turn, it more effectively contends the relationship between national and personal identity, with its central romance offering a ripe allegory for the modernization of China (the collectivism of Chinese Communism and its trajectory towards more individualized functions.) This, alongside an ambitious science-fiction turn, contextualizes the ways in which love is failed by politics and the cosmos alike. Ash is Purest White, alongside the next entry in this list, highlight both the force of individual emotion and its inadequacy in grander schemes. This coincidentally finds a kindred spirit in the next film, also about individual emotions in the face of progress and the unknown.

7. Ad Astra (James Gray)

Ad Astra is one of the decade’s best entries in the sci-fi space travel genre. Beautiful, almost religious space imagery restores awe to the unknown in a way that is sorely lacking from the modern imagination. Amid the film’s often unpredictable odyssey through space is a more humanist narrative about the ways in which trauma can be passed generationally. Brad Pitt’s alienated performance is carried for most of the film by his casting, until its jarring minimalism becomes wholly devastating in the face of the overwhelming conclusion.

6. Alita: Battle Angel (Robert Rodriguez)

The term “technarchy” may have been stumbled upon by chance to describe the film’s invading alien government, but the Ballardian definition feels appropriate for the Dystopian remnants of civilization–a hyper-technologized society that gets off on its own self-destruction. Cyborg mainstay themes–identity politics, new beginnings, and class conflict–are intact and clear, if not somewhat subverted to counteract modern cynicism by the film’s optimism. Politics aside, Alita is one of the most energetically paced and awe-inspiring spectacles of the year. Rodriguez and James Cameron use digital effects to their fullest, visually and conceptually creating a society that is as familiar as it is unique, ugly as it is beautiful. With her innocence and unbridled sense of duty, the heroine at the center is a strong mascot for self-actualization in such socially stratified times.

5. Gemini Man (Ang Lee)

Ang Lee continues to push the boundaries of cinema. An ostensibly simple narrative, of an aging hitman evading a younger clone of himself, is rife with provocative symbolism surrounding the ways in which new technology has radically altered our relationships with time, space, and ourselves by blurring the lines between the real and the virtual. Armed with high-frame-rate cameras and a uniquely advanced CGI reproduction of one of the most charismatic actors alive, Lee expands the affective capacity of new digital technology and puts it all on display in an immersive viewing experience beyond the scope of human perception. Lee, in invoking this definitive alienation, highlights the “real” characters’ numbness towards their experiences or actions, radically reframing the emotional legwork around a set of digitally generated pixels and proving his humanity in turn. This, paired with some of the most inventive and well-realized action choreography of the year, recalls the ways in which early cinema technology was likened to magic acts. Gemini Man and the way in which it has been critically maligned indicates a potential changing of the guard; of all the films made this year for mainstream consumption, none are as singular as this.

4. The Image Book (Jean-Luc Godard)

While Jean-Luc Godard’s canonized ‘60s films may garner ample discussion in film studies classrooms, such a myopic understanding of his entire oeuvre only represents a single decade of innovation in a body of work that regularly challenges the status quo. From the radical Dziga Vertov era and its political discourses to the Anne-Marie Mielville Son-Image collaborations to the more recent video essay work, each of his films after the New Wave signify a fundamental Godardian instinct to not only espouse complex dialectics but also to reinvent the expression of those themes. His latest work, The Image Book, is no different, retaliating over this modern era of neutered political cinema with an energetic history lesson about the medium’s legacy in (mis)representing the atrocities of the 19th and 20th centuries. Like many of his art statements, this is overlooked because of the ways in which it challenges the spectator with overwhelming formal reconfiguration and brash commentary; like many of this characterization, it readily deserves a viewing–if not for the ideals at its core, then at least for the very necessary reminder that film can be more than its limitations.

3. Richard Jewell (Clint Eastwood)

Clint Eastwood’s conservatism has always been an easy target. While it is true that right-wing ideals manifest commonly in his work, his detractor’s arguments usually neglect to notice his more progressive values. In that sense, I’ve always interpreted his cinema as confronting a more vertical political structure–between those with power and those without. Richard Jewell, Eastwood’s latest celebration of working-class American heroism, traps its audience in the helplessness of its title character, who is falsely vilified by the FBI and media after preventing the bombing at Centennial Park during the 1988 Atlanta Olympics. It is some of Eastwood’s most emotionally devastating and unsettling work yet, deromanticizing core American values via contemporary cynicism and institutional insecurity. With enormous empathy, he reframes Jewell–embodied by a career-defining performance from Paul Walter Hauser–into a strangely relatable symbol of those betrayed by the very systems they trust.

2. Under the Silver Lake (David Robert Mitchell)

Just as Mitchell’s second feature It Follows has its impact limited when taken in at face value, his polarizing follow-up Under the Silver Lake attempts its composite sketch of contemporary psychology from all angles. Its neo-noir structure is especially strengthened by its awareness of how socioeconomic factors have overcomplicated normal society and created an inadequate and superficial pop culture war to fill in the holes. Simultaneously satirical of modern slacker culture and sympathetic to the ways in which daily life has predicated such an outlook, the film channels horror, fear, and comedy alike from the familiar turned strange. Everyday situations camouflage Lynchian monstrosities, and Hollywood’s rich history–alongside L.A. folklore–of self-indulgence continues in new forms. Mitchell’s inclination towards ambiguity and the cult-like obsession of fans in parsing the film’s remaining clues both bolsters the film’s themes and highlights its longevity as a cult artifact for years to come. Speaking of LA…

1. Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood (Quentin Tarantino)

Who better than notorious cinephile Quentin Tarantino to channel the conventions of the Golden Age of Hollywood into a revisionist fairytale? In a climate in which nostalgia films that pine for the past glory of Hollywood feel less acceptable, Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood balances an optimistic industry worldview with more realistic truths. Heat is translated into bright exteriors that convey this underlying tension while grasping the geographical scale of the city and its possibilities. Softly lit interiors displace common criticisms of Southern Californian superficiality by discovering the intimacy and comfort of spaces, whether they be cramped like a 1966 Cadillac Coup de Ville or vast like a Hollywood mansion. The allure is simply an inherent aspect of the locale–an irrevocable and authentic aspect of the city’s aura. As many have said in the past: L.A. always plays itself.