Just a year since the cancer dramedy Me and Earl and the Dying Girl won big at Sundance, this year’s festival opened with another in the subgenre – albeit without the former’s teen-movie trappings – and it wears Sundance tropes like garlands (death, queer themes, quirky characters). Despite its tendency to fall into familiar characterizations, there’s much to like in its playful storytelling, not least from a winning performance by Jesse Plemons.

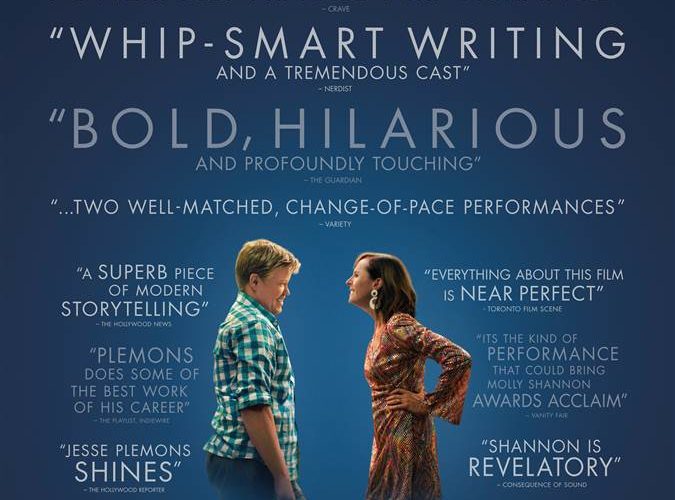

He plays David, a struggling comedy writer who returns from New York City to his childhood home in Sacramento after his mother Joanne (a terrific Molly Shannon) is diagnosed with cancer. The pilot he’s recently written has been rejected, his boyfriend (Zach Woods) has left him, and whittling away his time in his home town brings to light Sartre’s adage from No Exit that “hell is other people.”

Debut director Chris Kelly, himself a long-serving writer on Saturday Night Live, is willing to rip into his characters, and that mischievous tone is what sets it out from other mawkish cancer films (one where, all to often, all the suffering is done by people who don’t have cancer). Indeed, Kelly writes Plemons’ David as basically dislikeable, a self-centred brat whose misanthropic tendencies have stalled his life. His mother’s demise affects all around him – including his two largely ignored sisters (Madisen Beaty and Maude Apatow, daughter of Judd) – but all he can think about is himself.

And yet under Plemons’ sympathetic acting turn, David’s internal breakdown is not just a schadenfreudic watch, a slow-burning combustion that eventually lets rip in a very funny scene involving laxatives at a supermarket. Kelly’s film perceptively gets how grief is always partly self-aggrandizing. It’s about keeping up appearances and how you present your suffering to other people as much as it is mourning on your own.

Other characters are equally troubled, as well. It’s a testament that Kelly’s film has its heart in the right place that David’s conservative father (Bradley Whitford), unable to accept his son is gay, is seen in such a tragic light at his wife’s downturn. Still, it’s unfortunate that his character isn’t more richly written.

Sure, some of the film is tonally unfocused, flitting about from suburban Sacramento to comedy gigs in New York City, and a slightly misjudged sense that those outside The Big Apple are institutionally simpletons. But Kelly has a knack of playing tragic scenes as comic and visa-versa; the film opens with the grieving over Joanne’s death interrupted by an answer phone message by a prattish woman who had only just found out she was ill.

There’s also a scene-stealing performance from 14-year-old J.J. Totah, and June Squibb and Paul Dooley fit well as David’s grandparents. But these characters have the sense of set-decoration to the main event, as if Kelly’s script doesn’t have enough steam with his core set of characters. Indeed, had Kelly been more focussed with David, the film’s conclusion might have been more moving. Either way, Kelly’s earnest, reportedly auto-biographical film has a lot of laughs and is best when it’s most deeply personal.

Other People premiered at the 2016 Sundance Film Festival and opens on September 9.