The question that Hermann Vaske has asked for over two decades is a large one. Why Are We Creative? There’s no blanket answer — no right or wrong notion of the philosophical ramifications trying to put your own personal interpretation into words conjures. So it’s interesting that he would end his film with a statement explaining how the thousand-plus subjects he asked changed the way he looks at the world. It’s interesting because we don’t know if that is true. After traveling the world to confront geniuses in their respective fields and creating an art exhibit with pages upon pages of written and drawn summaries of definitions spoken, Vaske hasn’t created any concrete evidence towards the worthiness of the endeavor to himself besides that single line of dialogue.

One therefore has to look past what it is he believes the film has always been. We have to forget Vaske completely because his brief interludes sprinkled throughout are merely used as segues or loose chapter headings for the audience’s journey. He’s a curator rather than the subject despite how things initially seem. He might be learning and changing as the years go on, but he has documented the text that inspired such unseen metamorphosis instead of the process itself. I don’t say this as a way to declare the final project a failure, only to explain the difference between intent and reality. Vaske intended to discover a universal answer to his query through volume and comparison only to find contrast, mystery, and fluidity in its place.

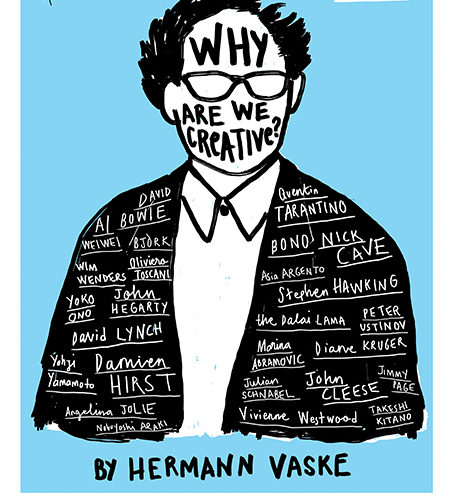

What in effect happens is that the film asks its audience the same question before presenting a litmus test of disparate thoughts courtesy of luminaries, celebrities, and people otherwise completely different than us. There are no random strangers on the street being accosted or respectfully polled. It’s Marina Abramovic, Nelson Mandela, David Bowie, Angelina Jolie, Vivienne Westwood, and Frank Gehry. It’s people who have had the time and mindset to approach a question of this weight and breadth, those with the ego to prepare snippets of ideology they have cultivated as a means to give their artistic essence form beyond the unpredictability of external tastes and era-specific ideals of beauty. Everything said is thus tainted by the rarified air of artificial pithiness that ultimately might lack true spontaneity.

Rather than take what they say to heart, I found worth in how their words are delivered. Many retreat internally to selfishly define their work — something you cannot blame them for doing considering these interviews are often press tour related whether off-the-cuff or on the red carpet. When you’ve conditioned yourself to this machine that revolves around marketing speak, you find that every question has a distinct relevance to the topic at-hand regardless of its complete detachment from the media circus generally affiliated with a camera in the face. So we hear about how these men and women can’t live without their creativity and how it drives them. We listen as they tiptoe (or don’t) around the desire to not be special by explaining how special they are.

Others look upon the question literally like John Cleese going on about his work with a psychiatrist to try and decipher what conditions foster creativity above all else. Some like Yohji Yamamoto remove themselves from the equation to define art as a form of communication by saying we just “want to be understood.” Some speak about rebellion and how creativity in politics can only upset the status quo and thus spark conflict. And even fewer (by my count it’s David Lynch, the Dali Lama, and Stephen Hawking) get to the heart of the matter to (jokingly or not) defuse things by equating creativity with humanity. We are creative because we are alive. If we’re truly being honest with ourselves, that’s the correct answer. Success should be inconsequential.

This is the aspect of Vaske’s film I found misguided. You cannot hope to reach a consensus if you’re just pitting the greatest voices and minds from different specialties together. Whether these people are rich and famous or notably brilliant, they’re all on the same level as far as success is concerned. They have found a way to leverage their creativity into a career, utilized their creativity to shake up the status quo, or were lucky enough to be alive at a moment where those with the power to validate their creativity did. It’s very cynical to say this, but everyone onscreen was speaking from a position of privilege as far as being able to let their creativity define them. The majority of us don’t have that luxury.

So while the words spoken are inspirational and obviously affected the director (even if his asking the same thing over and over doesn’t necessarily prove it), the premise is flawed. Björk speaks about how everything is creative if the maker is passionate about the work (like her family of fireplace makers). They’re who I want Vaske to ask his question because they are the people who truly do it because they must. They’re the ones removed from accolades and the history books, the ones who find time to create in the few spare minutes they can afford to supply themselves every day. All the interviewees in this film were that person at one point in their lives. Give me a time machine to hear their answers back then.

Why Are We Creative? is now playing at the Venice Film Festival.