In 2015, Brady Corbet released The Childhood of a Leader, a flawed and somewhat immature movie but arguably one of the most bombastic directorial debuts of recent years. Now we have Vox Lux, his deliriously incendiary follow-up, a film about a teenage girl who survives a shooting and becomes a national symbol of hope only to later descend into dissolute pop-stardom.

It’s pleasing to note that the actor-turned-director seems to have forgone none of Childhood‘s aesthetic swagger and misanthropic bite in the process of making his second feature. He has, however, significantly fine-tuned his nose for satire in that time and what we have as a result is not only a thrilling examination of fame and violence in the 21st century and how the two are intrinsically linked, it might also be 2018’s most blistering cinematic provocation this side of Lars von Trier’s The House That Jack Built–but more on that guy later.

Corbet’s screenplay is split down the middle with the first half beginning on Staten Island just after the turn of the millennium where, in the very first scene, a 15-year-old girl named Celeste (Raffey Cassidy) takes a bullet to the neck. As she recovers in hospital she writes a song with her sister (a fascinatingly subdued Stacy Martin) that somehow captures the country’s mournful mood while lifting Celeste to national fame. The sisters then move to New York where they find a manager (a revelatory Jude Law) for Celeste, who whisks them away to Europe to record an album.

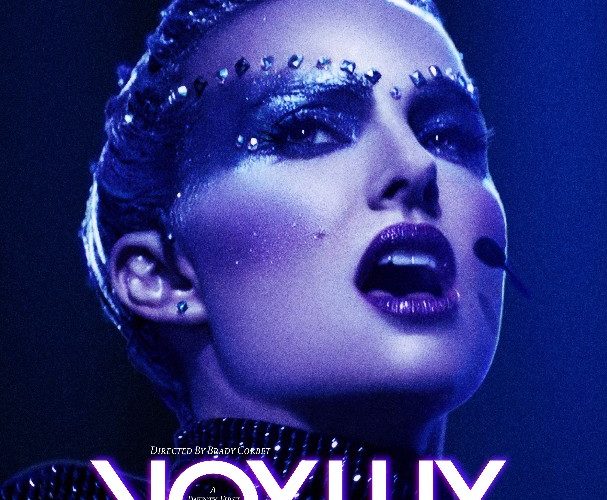

A life of debauchery is about to ensue but just as the film teeters on the edge of that problematic precipice, Corbet cleverly looks away, jumping forward 15 years to the point when Celeste (now played by a rampant, scenery-chomping Natalie Portman) has reached diva status and is about to perform the final concert of her tour, which is set to take place in her hometown. Corbet cleverly twists this tale of the meteoric rise by turning it into a kind of nightmare and one that runs in parallel with the most iconic violent acts of the era: notably Columbine, 9/11, and the modern-day terrorist attacks in Europe often claimed by ISIS.

It’s interesting that Corbet always seems to gravitate towards sociopathic characters in his films as both actor and director (Martha Marcy May Marlene, Funny Games, Simon Killer, Childhood, etc.). Those movies have featured sadists and cult leaders but Celeste is a little more tricky to categorize: strong-willed and ruthless, sure, but oddly emotionless, too–which is probably what makes her so captivating to watch. Cassidy’s tremendous central performance is as aloof as they come, reminiscent of her previous work in Yorgos Lanthimos’ The Killing of a Sacred Deer or, indeed, of Stacy Martin’s in von Trier’s Nymphomaniac (although less interested in sex than success).

Indeed, the echoes of the Dancer in the Dark director abound in Vox Lux and one would be hard-pressed to watch the film without thinking of the troublesome Dane. The poetically titled chapters into which Corbet has split his screenplay have Lars written all over them but the most blatant nod is surely Willem Dafoe’s ironically banal narration–a clear descendant of John Hurt’s in Dogville. Derivative or not, however, that narration is a delight, as eloquently written as it is insightful and often incredibly funny, not least when we get to the film’s astonishing punchline.

With an ending Lars von Trier would be proud of, Corbet, nevertheless, sets himself apart in other ways, most notably by managing to provoke without the need for any real gratuitous imagery. The best example is a terrific time-lapse of videotape footage from the girls’ travels through Europe that implies all kinds of lurid behavior without having to show a thing. There is also that incredible baroque style that Corbet should reasonably now call his own: a world built on shadows, natural lighting, Lol Crawley’s analog cinematography, and, most significantly, Scott Walker’s scores. For Vox Lux the journeyman composer has provided another jagged Bernsteinian masterpiece, one that charges each scene with all the grandeur and menace of an approaching iceberg. It also works in terrific counterpoint to Celeste’s perfectly mediocre pop tunes, which are provided by Australian artist Sia.

Childhood of a Leader was a film about how little early traumas can plant the seeds for fascism and it played like a brilliant gloom metal cover of Haneke’s The White Ribbon. Vox Lux, however, is getting at something different, perhaps that our lust for celebrity has had a more disastrous effect on the world than we might like to believe. Indeed, Corbet’s second feature owes a debt or two to filmmakers reveling in provocation, but it is no doubt the work of a daring original.

Vox Lux premiered at Venice International Film Festival and opens on December 7.