There comes a telling moment near the beginning of The Mountain when Jeff Goldblum’s doctor turns to his newfound apprentice to explain the workings of a camera’s aperture. He’s a shady lobotomist (is there any other kind?) and has just hired the younger man to take photos of the women he operates on, both before and after their procedures. He explains to him that were he to set the aperture to F11 not much light would get in. You would be within your rights to say that the film itself is set to F11, just as its creator, Rick Alverson, might be too. As visually overcast as it is emotionally dead-eyed, The Mountain is probably the most intentionally–and unwarrantedly–bleak film you’re likely to see in 2018, a draining head-fuck of a movie with perhaps some stuff to say about misogyny, creativity, and mid-20th Century mental asylums.

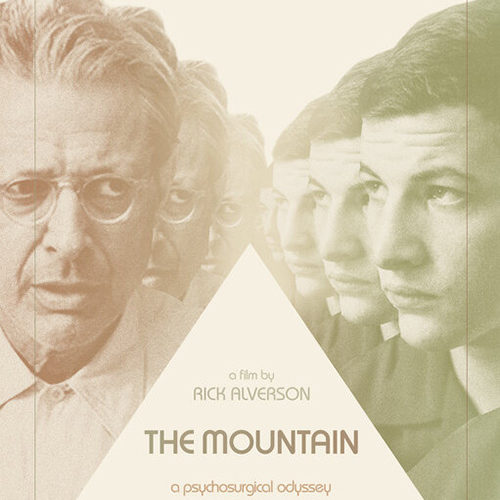

The Spokane-born director began his career making movies about immigrants (The Builder, New Jerusalem) but in the past decade has attained a certain notoriety for writing scripts that blend disillusionment with an apparent disgust for screenwriting norms. His latest completes a unique trilogy alongside Entertainment (of which I was a fan) and The Comedy, which was lambasted by a number of critics at the time. The Mountain stars Tye Sheridan as Andy, the aforementioned photographer who, following the death of his father (an underused Udo Kier), goes on the road with one of his dad’s acquaintances.

The man is a womanizing physician named Wallace Fiennes (Goldblum) and Andy chooses to follow him in the hope of finding his mother, an ice skater who suffered from a mental illness and whom Fiennes may or may not have operated on. One of the scant enjoyable factors here is just how much Goldblum revels in the role, sporting a quiff worthy of David Lynch and distorting those charming fidgety mannerisms into something unnerving and quite perverse. I must say it’s a pleasure to see him with something more to chew on for a change. I’d begun to grow ever so tired of those–admittedly not-unpleasant–Wes Anderson bit parts, Marvel gigs, and novelty sitcom appearances. Sheridan, a mercurial talent who may as well have been asleep during Ready Player One, isn’t asked to do a lot here (he’s basically mute) but his on-screen presence and furrowed brow are more than enough to hold the eye.

The great Denis Levant even shows up late on and while his vaudevillian theatrics delightfully play in such stark counterpoint to the pea soup around him, it did not take long for his shtick to wear thin. We should expect as much. Indeed, as a filmmaker Alverson seems determined to sour our expectations of notable actors and narrative tropes. Andy’s journey with Fiennes goes from one women’s asylum to the next as he takes a front row seat to all the horridness the man might have subjected his own mother to. He also has to observe his seedy seduction of women in the outside world. He soon does the math.

The Mountain is set somewhere in the 1950s and the director has gone to great lengths to give his film what appears to be the look and feel of that era’s defining Americana art, most notably Edward Hopper. Cinematographer Lorenzo Hagerman (who worked with Rodrigo Prieto on Amores Perros) shoots the proceedings beautifully, all things considered, and captures a truly striking image early on of Andy’s mother pirouetting in slow motion on the ice. As it turns out the mountain which the title refers to is also a piece of art, a kitsch painting we see at two significant moments in the film. If there was a grand statement being made here about the mass production of images; the death of imagination; or a misplaced appreciation for artists, or whatever, it was quite lost on me, even if the director has a boozed-up Levant basically rant explicitly about it.

As an uneasy admirer of Entertainment, it took me a while to pinpoint exactly why Alverson hadn’t managed to repeat that film’s delicate balance. One need only read a handful of interviews with the director to get some idea of the man’s intelligence, however, with the greatest respect, it seems a brilliance of the removed, academic kind. Considering that the film was co-written by Dustin Guy Defa (whose debut feature Person to Person was such a blast last year), it’s strange that The Mountain ultimately comes across as an experiment of the sort that Goldblum’s character might have been interested in. It’s clever, cold, and devoid of the one thing it assumes to be interested in: humanity.

The Mountain premiered at Venice 2018 and opens on July 26.