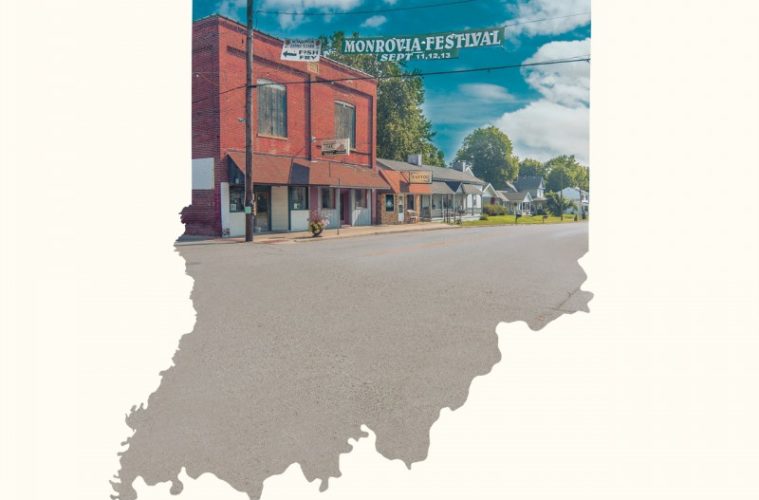

Veteran filmmaker Frederick Wiseman adds a quaint but important little chapter to his great oeuvre with Monrovia, Indiana. It’s 143 minutes long, which is about the equivalent of an EP by the octogenarian’s standards, however running time is not exactly the most significant or intriguing departure Monrovia represents from Wiseman’s more recent output. Since National Gallery dropped in 2014–a rarity for the director in that it looked a topic from outside the United States–the director has released a masterful diptych of New York-set works, one which focused on what is said to be the most diverse neighborhood on the planet (In Jackson Heights) and another that looked at what is arguably the crown jewel of liberal, East coast democratic society: The New York Public Library (Ex Libris). According to a 2010 census, the town of Monrovia boasts a population of little more than 1,000 people and upwards of 97% of them are white. Some refer to the state of Indiana as the “reddest” in the Midwest. Indeed, quite the departure.

One of the more pleasing, if not necessarily surprising things about Monrovia, Indiana is that Wiseman treats the locale and its residents with just as much respect as he did with any of those recent gargantuan projects, inviting us once again to sink into the rhythms of the particular world he has chosen to document. Seemingly as invisible as ever to those he films, the director shows the pace of this particular small-town life: the livestock; the farming; the local eateries and bars; the tattoo parlour; veterinarian; the high school; the churches; the gunshop; the town fairs, and my personal favourite: a Masonic lodge meeting that Dale Cooper could have shown up to without causing much fuss. After the kaleidoscopic diversity of his previous two films, Monrovia was always going to prove a tougher job and the film does lag on the occasions when the director is left focusing, for example, on the tinned good section of a local supermarket.

Still, there is much to savor. Wiseman is well known for his objectivity but another of his most enduring traits has been a dedication to showing audiences the hard, under-appreciated work that is constantly being done by small social organizations and local councils. In Monrovia we’re treated not only to lengthy discussions on town expansion and what exactly defines a fire hydrant but also, most endearingly, to one woman’s mission to get a new bench put in outside the town library.

Wiseman’s clear fascination with faces–those that talk and those that listen–not only makes these otherwise excruciatingly banal conversations compelling and empathetic, they occasionally have the profound effect of changing how one might think and feel about things like benches and fire hydrants. This is the 46th documentary Wiseman has made in his half-century career and, prolific as he may be, it’s dreadful to think that we may not see so many more of them. Indeed, if one has a few hours to spare there is no safer place in cinema to flock to than in Frederick Wiseman’s hands. In looking at both the macro and, as with Monrovia, the real micro of North American life, his films continue to appeal to one’s better angels and enrich the soul like few others. We hardly need to say but the world is in short supply of that kind of empathy right now.

One might be startled to hear that there’s no mention of Trump in his latest film, given the fact that three times as many people in Morgan County (in which Monrovia is situated) voted for him over Hillary Clinton. That may, however, ultimately prove to be to the benefit of Monrovia, Indiana. Indeed, the United States is a more divided place today than it has been for a very long time and it’s hard to think of another filmmaker with the same priceless ability to show life, in all its mad variety and with such clarity, on–and more importantly to–both sides.

Monrovia, Indiana premiered at Venice 2018 and opens on October 26.