A suicide. A stillborn baby. A woman holding the latter as she leaves the former to show her husband and the now widower father the results of the harrowing night thus far kept off-screen. We hear the wind blowing as the camera pushes in towards Lizzy Macklin’s (Caitlin Gerard) haunted face in silent shock. Only after she washes the blood from her body and sees Isaac (Ashley Zukerman) place her rifle against the table does she speak and only after mother and child are buried do we finally start to receive some answers. Isaac is taking Gideon (Dylan McTee) back to the city so he can settle his affairs and let his wife Emma’s (Julia Goldani Telles) family know what occurred. This leaves Lizzy alone to remember everything.

Director Emma Tammi therefore ensures we understand her western horror’s pacing and the winding psychological road through Lizzy’s mind that screenwriter Teresa Sutherland follows. The quiet isn’t a fluke, but an attribute of living on the American frontier during the 19th century. Its deafening silence is what confronted her upon settling down and what she must now combat post-tragedy. Where it used to be representative of the isolation she and Isaac chose for their future by being the ones who left, that silence is currently a byproduct of sound’s absence dictated by those she’s lost and those who’ve left in response. It’s here in the turmoil of grief and fear that she recalls her past demons. And it’s in the gaps of those recollections that new ones appear.

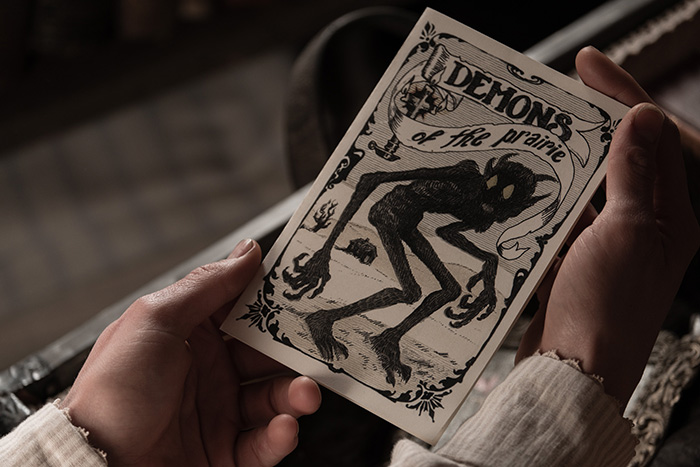

As a result, The Wind moves back and forth through time in accordance with what Sutherland and Tammi choose to let us know. First we witness the events of that stillbirth from the womb of a corpse and then it’s time to meet Emma and Gideon less than a year prior before going back further to experience Lizzy’s own embattled pregnancy. Talk of malicious forces arises once the two women find themselves struggling to fend off feelings of loneliness and perhaps panic as far as what it will mean to raise a child so far from civilization. Maybe these instances of evil are a manifestation sowed by a handmade pamphlet listing the numerous demons this prairie has to offer or maybe they’re nothing more than a terrorizing breeze.

The shifting is easy to discern as Lizzy’s hardened gaze is softened with a smile via flashback. Her present finds her alone and fearful of what she cannot see while the past portrays a sense of hope until her new neighbors begin to bring back the dread she had thought disappeared long ago. The wind transforms into violent wolves and eventually black-eyed human vessels that shape-shift to infiltrate her home while Isaac is gone. So rather than tag along with the men as they ride off to some adventure like a prototypical western, we’re tethered to the homestead with the women lost upon their personal islands and deprived of human interaction. It’s enough to make anyone go crazy and also the perfect scenario for crazy to become reality.

Which is happening is in the eye of the beholder and his/her interpretation of a kindly reverend (Miles Anderson) passing through. It can be difficult to discern what we’re shown is authentic and what’s hallucinatory subterfuge, but I do believe the difference stems from the when of each action. These characters don’t arrive at their destination with a severed grip on reality—that’s something learned with time and/or thrust upon them by malignant beings outside of the realm of possibility. With death comes a question of faith and with that uncertainty arrives a door inviting all sorts of nefarious creatures in to fill the void. So is the lamb dead and eviscerated? Or has it been standing there alive the whole time? Can Lizzy and Emma trust either?

The answer is of course “no” because there’s no time. If something is coming for them, they must do whatever is in their power to protect their unborn children. The men don’t understand because they’re free to come and go as they please, each sojourn to the city a chance to meet with people that aren’t their wives. So Lizzy and Emma’s cries of demons knocking on the door at night have more meaning than simply the nightmares of mothers. The response they receive is no different than those they’ve received their whole lives as subservient housemaids fulfilling duties towards their husbands alone. Their pleas to escape these vast plains with nowhere to hide fall on deaf ears because the men refuse to empathize with their unique plight.

So don’t dismiss The Wind as some retread concerning isolation as a theme when who these women are and the era in which they live allow it to represent a lot more. It’s yet another example of why we need more women writers and directors to tell stories from their perspective and not a skewed second-hand interpretation of what it means to be a woman in a historically oppressive America. That doesn’t mean it also isn’t an effective horror on the surface with supernatural antagonists growing more vicious as our heroine progresses through the torment of living amongst uncharted land holding secrets no one can pretend to know. Sutherland’s script is working on multiple levels while Tammi’s formal aesthetics reveal an artist in complete control of her vision.

The Wind opens in limited release on April 5.