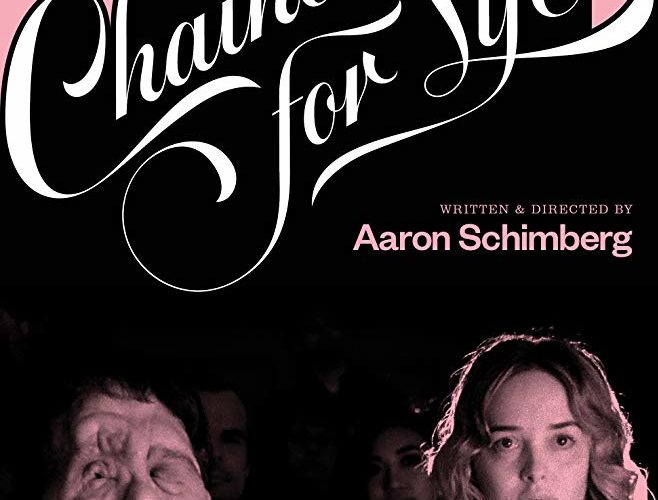

“Do you feel like the story is exploitative?” a journalist asks actress Mabel (Jess Weixler) about the new film she’s starring in, early into Aaron Schimberg’s brilliant second feature Chained for Life. In a meta-melodrama that constantly seesaws between fiction and reality, sprawling across a labyrinthine and multi-layered narrative that seamlessly jumps from one textual plane to another, I found myself wondering whether the question was in fact leveled at Schimberg’s own work.

Chained for Life unspools as a film-within-a-film. It follows a thick-accented German director (Dick Tracy and Hook child star Charlie Korsmo, here sporting a Fassbinder beard-and-glasses combo and a rusty Herzog voice) as he makes his English language debut in US soil: an art-horror about a mad doctor and his patients, all displaying an assorted range of physical differences. Ostensibly in an effort to stay true to his subject, Herr Director (as per the film’s credits) has cast people with real-life genetic disabilities and irregularities–a giant, a little person, conjoined twins, and the indisputable star of the show: a man known as Rosenthal and played by a terrific Adam Pearson (the neurofibromatosis-afflicted thespian of Under the Skin fame). Opposite Rosenthal stars Mabel, a blind young woman graced with a radiant beauty that rekindles Chained with the musings on actors’ good looks penned by Pauline Kael, and which Schimberg had used as introductory quotes. Unperturbed by Rosenthal’s appearance, Mabel befriends her co-star, and while the friendship never gives in to flirting–at least not in all narrative planes–and Chained does not spell out whether the relationship develops out of her fervent obedience to the Method or a sincere attraction, the interactions between the two do make room for some unexpectedly heartwarming moments. So, does the story feel exploitative?

Fortunately for Schimberg, the answer is a resounding no. Of course, Herr Director’s Herzog/Fassbinder stand-in may well be guilty of sensationalizing his cast’s disabilities–in one particularly cringeworthy exchange, and Rosenthal’s first scene in the film, Korsmo commands him to step out from the shadow and “into the light,” an order that reduces Rosenthal to a Phantom of the Opera-like freak–but this is a fault Schimberg does not commit. Never once does Chained ridicule his subjects, whether they’re egocentric prima donnas (The Mend’s Stephen Plunkett) or those with congenital differences: far from urging us to laugh at “the undesirables” (as the title of Herr Director’s new oeuvre would have it), Chained invites us to laugh with them.

After all, Schimberg’s quirky script and Pearson’s moving performance craft Rosenthal as an everyday bloke mired in all the fears and insecurities you’d expect from a newcomer facing their first big role. And while cinematographer Adam J. Minnick’s perceptive camerawork and POVs literally force us to see the world through Rosenthal’s eyes–as much as the reactions on the faces of those he bumps into–Chained thankfully circumvents any simplistic put-yourself-in-their-shoes arguments. Schimberg’s second feature is not an exercise in pity, but a delightful attempt at debunking the meaning of normalcy, which neither keeps its subject at an arm’s length nor suffocates it under the pretense of political correctness.

Caged in another man’s narrative and physically sealed off from the “normal” people’s lives outside the set (in an apartheid-like scenario, Rosenthal and fellow disabled actors and actresses sleep in the deserted hospital wing where the shooting takes place, while the other cast and crew stay at a nearby hotel), Herr Director’s heterogenous cast spend their nights fashioning their own alternative scripts. It is here that Chained adds another narrative layer, and if the result can be disorienting, getting lost in Schimberg’s sprawling edifice is a price worth paying: every ruse underscores the film’s attacks on normalcy, while trumpeting the cast’s struggle to reclaim their own voice over and against the pariah roles the showbiz has relegated them to.

Also programmer at Brooklyn’s Spectacle Theatre, Schimberg intersperses chinephilic references all throughout Chained’s 91 minutes–aside from Korsmo’s resemblance to Fassbinder (whose 1971 on-set satirical Beware of a Holy Whore echoes Chained’s own vibes) and Herzog (who did work with an all-little-person cast in his 1970 Even Dwarfs Started Small), something in the shoot’s playful and anarchical atmosphere echoes Truffaut’s 1973 Day and Night. Adam J. Minnick’s Super 16mm graces the film with a grainy, near-hazy look; panning and traveling shots browse through rooms packed with people capturing the set dynamics in all their minutiae. There’s gossip, boredom, inter-cast drama, and even some whiffs of danger after news break out that a facially disfigured murderer is on a killing spree nearby the shoot. But it’s a faint threat reined in by the pyrotechnic buzz Schimberg’s set bursts with. For a film zeroing in on disfigurement, Chained is remarkably cruelty-free. Nowhere is Rosenthal humiliated by other cast and crew–at least not explicitly; any attempts at bullying, however low-level, are quickly diffused with scattered self-deprecating quips. It’s a strategy that leaves no clearly identifiable villain, but also considerably narrows the gap between Rosenthal and the audience. More than a film about physically different people, this dryly humorous and ever-perceptive oddball focusses on our relationship toward that difference, and the uplifting moment when cinema ceases to sensationalize it, but lets it act as an engine of creation.

Chained for Life screened at the Tallinn Black Nights Film Festival and opens on September 11.