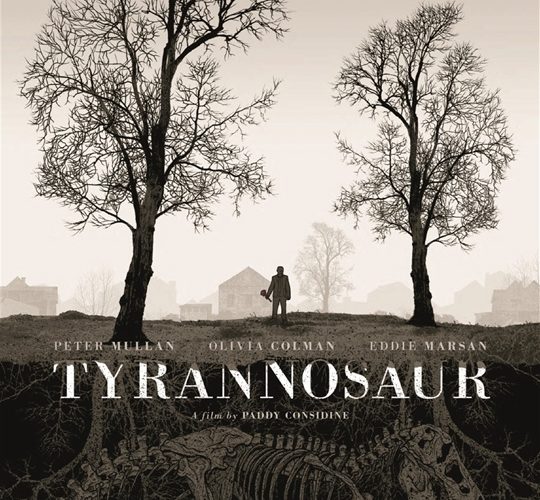

Certainly one of the darkest films at Sundance 2011, thespian Paddy Considine‘s directorial debut Tyrannosaur tells a simple story: girl finds boy, boy wants girl but she’s already spoken for. Only here the man who’s spoken for her is a sadistic wife-beater (Eddie Marsan) and the new man (Peter Mullan) is an old bear with a vicious, dangerous temper himself.

These are not good men to get in bed with. But Hannah (Olivia Colman) doesn’t know any better. Considine’s world is dark and dreary, full of dying friends and rabid dogs who must be put down. That Mullan’s Joseph puts down the dog with a baseball bat is more of a specific character trait than anything else. Mullan, who’s been around for years (you might remember him as the corrupt coyote in Children of Men), has never been better. He moves like a tidal wave, constantly about to break. It’s a tight performance and, like the rest of the film, not easy to watch.

Hannah, on the other hand, is constantly breaking. Mullan and Colman spark a chemistry among the ruins of both of their lives. Considine, who also wrote the script, doesn’t go into the too much detail, outside of digs made at Joseph via his dying best friend’s daughter or a short breakdown Hannah has in front of Joseph, admitting some of her husband’s past sins. It’s this lack of information that allows these two actors to find some sort of romance within the tragedy.

Considine and cinematographer Erik Wilson (who also shot Sundance hit Submarine, which co-starred Considine as well) obstruct many of the frames as though the camera itself can’t look, desaturate most of the color and offer unflattering spotlights of their leads. Mullan’s shrouded in darkness most of the time, save one particular scene in which we see him smile. Hannah smiles as well, over the sound of an Irish bar song. It’s a dreamlike hiccup in the middle of a short, brutal narrative.

This is, above all else, a victory of collaboration. Though Considine’s vision is true and complete, it’s also sadistic and a bit off-putting. For a long while most of the violence piles on in such a way it feels gratuitous more than anything else. Then, something happens. Mullan and Colman breath life into their characters; they become kindred spirits through the violence. It’s not pretty, but it works.

The two leads deserve all the acclaim they can get and most likely much, much more. Even when Considine pushes Colman’s character to an unexpected brink, she anchors Hannah back in and we stay with the story. Everybody’s on the same playing field here. Everybody knows exactly what kind of film they’re making.