As we’ve learned time and time again, a foreign director’s transition from their native country to Hollywood can often be a difficult road to traverse, with not only language barriers perhaps getting in the way, but an entirely different production system from top-to-bottom to get acquainted with. 2013 brings a trio of South Koreans attempting to hit it big in the US, as we recently witnessed Kim Ji-woon make his US bow with The Last Stand, while Bong Joon-ho is gearing up for a Snowpiercer release later this year and now Sundance Film Festival has provided the premiere of the latest work Oldboy director Park Chan-wook, with his dark, diverting family drama Stoker.

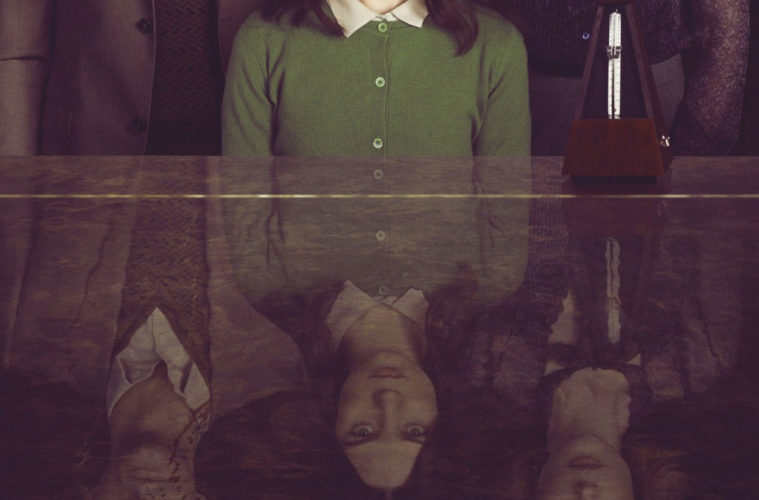

Scripted by Prison Break‘s Wentworth Miller, the story opens on a tragedy — Richard Stoker (Dermot Mulroney) has passed, leaving his wife Evelyn (Nicole Kidman) to take care of their now deeply troubled daughter India (Mia Wasikowska), as his mysterious brother Charlie (Matthew Goode) enters the picture. Saying anything more plot-wise would ruin the fun to be had, but from quite early on, it’s apparent that our director has not suddenly made the shift to understated territory, as the themes are heavy and apparent from the start, with our characters being portrayed as larger-than-life and as highly stylized as the visuals that accompany them.

Introducing the film, Park Chan-wook said this is a project that very much exists inside a world in his own mind and he hoped we “enjoy this dream as much as [he] enjoyed dreaming it up.” If one opts dream out for nightmare, then they would be more prepared for the events to come. Applying an impressionistic technique moreso than any of his previous films, it takes until the second act to fully get immersed in this story. Complete with a multitude of flashbacks, our director will often repeat imagery again and again (and again), as well as shift our understanding of what is truly before our eyes (a hanging light India turns on and swings in the basement with then suddenly jump to Evelyn and Charlie upstairs, or Charlie will fill the frame out of nowhere to deliver an unsettling line).

This go for broke style can be quite unnerving and instead of ratcheting up the tension, it just feels slightly off in the first act — dinner table scenes are often captured with a constantly moving camera that feels like our actors or waiting for their cue instead of naturally existing in this world. But eventually, as the pieces of this overarching puzzle start to fall together and the dots are connected, it’s easy to buy into what our director is aiming for. This is his own fever dream as much as it is India’s, and as the violence is compounded and revelations build, it turns into a savagely fun ride.

First and foremost, Stoker confirms Park Chan-wook status of a visual master, thoroughly enjoying the many tools at his disposal. Not only does the film contain one of the best dissolves in recent memory, but our director is exceptional at capturing the creepy, little moments. Whether it’s the terrifying use of a belt, a spider crawling into unwanted places or a bloodied pencil getting sharpened, he heightens the gothic atmosphere with these small visual touches that add up to a dizzying experience, with some additional help from Clint Mansell‘s grand score.

Taking a major nod from Alfred Hitchcock‘s Shadow of a Doubt, Park Chan-wook has crafted his own twisted coming-of-age tale with Stoker, as the sullen India finally finds pleasure in the most unsettling of ways, learning to deal with bullies at school and a disturbing love triangle unfolding before her eyes. As uncomfortable as we may be at the outcome, it’s difficult not to simply enjoy the feral, visceral events our director has concocted. Despite some missteps along the way in execution, Park Chan-wook has come to Hollywood in about the boldest way he can and his distorted vision is a welcome one in this terrain.