Do not be fooled — Youth in Oregon is a drama through and through. While some of its marketing may suggest a more comedic tone, Joel David Moore’s directorial choices, combined with the film’s poignant — if often scattered — thematic musings are centered on heavy drama. Unfortunately, the first two-thirds of Youth feel like a war between Moore’s aesthetic sensibilities and the thematic tonal balancing act attempted by the script penned by first-time writer Andrew Eisen. I would argue that the ideal presentation of a “dramedy” is combining genuine humor with emotional weight in the same beat. If a storyteller can blend them organically — accentuating the impact of both by contrast — they have succeeded. By this definition, Youth in Oregon is not a successful dramedy. Instead, its first two-thirds feel like a drama and an occasional comedy, separately, each existing on their own plane and rarely passing each other by with a wave. However, what Youth in Oregon ultimately becomes is a deeply affecting examination of decisions and goodbyes with a lasting final impact. Unfortunately, it takes so much of the film’s brief runtime before it realizes this, existing in its majority as an inconsistent, puzzling experience.

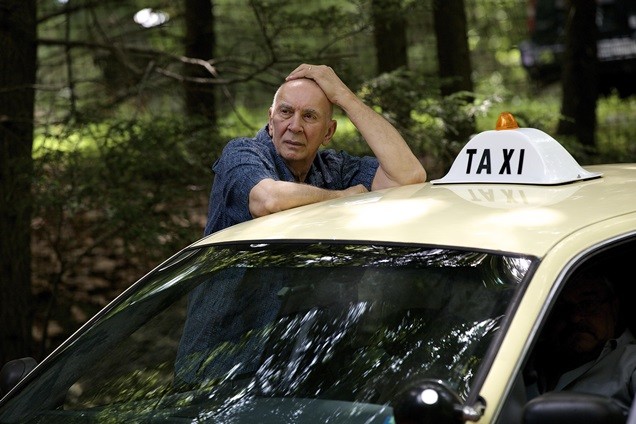

Youth in Oregon centers on Raymond (a supremely affecting powerhouse performance by Frank Langella), who announces to his family — including his son-in-law, Brian (Billy Crudup), and daughter (Christina Applegate) — that he has decided to travel to his hometown of Oregon to be euthanized. The rest of the film takes place during the road trip Raymond takes with his wife, Estelle (Mary Kay Place), and Brian. Along the way, heartbreak and revelations unfold as the trio near Oregon, meeting up with old friends and family along the way as Brian tries to convince his embittered father-in-law that life’s still worth living.

The script tries to strike a balance between everyday life humor and its darker, unavoidable thematic core, often to jarring results. This tonal imbalance is apparent in the script, and accentuated by Moore’s clinical approach to the material on a technical level. His camera often has a slow glide to it, steady and precise in its movement, in a way that feels observational. This approach works better in the latter-third of the film, but mostly comes off as a cold, removed layer of foam over what could be a wide-open, beating heart.

By the time the third act arrives, the script, the performers, and Moore all seem to agree that they are in strictly dramatic territory, which is a welcome respite from the off-kilter humor that is peppered inconsistently throughout the majority of its runtime (not to mention an ineffectual and confounding B- or C-story I will not discuss). While many often complain of comedies going off the rails in their final stretch and losing all funny bits, the darker tone is a welcome and assured decision for a movie about a man set on being euthanized.

Once this happens, it feels like a wave of relief for the viewer — despite the heavier, more morose tone it takes on — because it feels like the film stepping into its own. If you’ll take an analogy: so much of the first half feels like watching a pair of slippers aside a pair of feet. Each feels hollow or incomplete when set next to the other, making for a certain instinctive nudging in one’s gut insisting that they should come together. Finally, in its last push, the feet step into the slippers, and regardless of how powerful the result, it is satisfactory, and far more compelling nonetheless for it having happened at all. In this way, the slippers are Moore’s aesthetic choices, and the feet are the script’s most poignant, resonant tonal elements.

At its core, Youth in Oregon is looking something smack in the face that many of us don’t want to consider, but that is so obvious and inevitable: saying goodbye. Because of this, the most beautiful and crushing aspect is in its resolution. Without spoiling anything, I’ll just say this: you’re waiting throughout the film for the plot — specifically, Langella’s choice — to resolve itself. Neatly, satisfactorily, even happily. Except then it hits you that in life, in this situation, there is no neat answer. The movie ruminates on this in a raw and extremely moving way in its final moments, ending on a shot whose simplistic elegance will stick with me for a while. Youth in Oregon is a struggle to get through — in its frequently puzzling choices and missed opportunities — but it opens up and reveals itself with genuine catharsis in its closing that just, maybe, is worth the trip for the patient, forgiving viewer.

Youth in Oregon opens in limited release and on VOD on February 3.