It was said upon the release of Toy Story 3 that the franchise was done as far as Woody (Tom Hanks) and Buzz Lightyear’s (Tim Allen) adventures were concerned. These sentiments made sense: it ended nicely on a logical breaking point, the boy whose name adorned their feet grown-up and gifting them to a new owner (Bonnie) who promised a warm future of happiness and play. Because simply retiring the characters would be dumb, Pixar decided to branch out into a trio of short comedic vignettes and pair of sitcom-length episodes that focused on different peripheral figures who deserved their time in the limelight. The studio could have continued in this direction for years and probably would have if not for an epiphany.

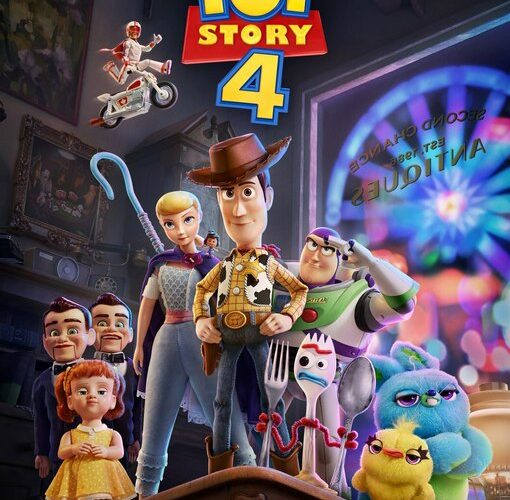

The braintrust got their light-bulb moment in the form of an obvious reunion: the usual gang and old friend Bo Peep (Annie Potts). So they (spearheaded by original director John Lasseter and co-writer Andrew Stanton) drew up a treatment, handed it to Rashida Jones and Will McCormack to flesh out a standalone effort that would prove more romantic comedy than action adventure, saw it land in others’ laps once that duo left due to “philosophical reasons,” and ultimately found its way back to Stanton and Stephany Folsom to put the finishing touches on first-time feature director Josh Cooley’s shooting script. And while that many cooks will always give a discerning viewer pause as to a finished product’s quality, Toy Story 4 was somehow baked to perfection.

A big reason is that they sort of reset things back to before those aforementioned shorts. Where they retained a hierarchy with Woody still residing at the top despite Bonnie (Madeleine McGraw) already having a core set of toys with Dolly (Bonnie Hunt) in charge, this installment remembers her place. This is crucial to what happens next because it forces Andy’s favorite cowboy to look in the mirror and dislike what he sees. Woody doesn’t just get to go on living as he always had because he’s the star of a film series. He doesn’t get to make mistakes and guilt the others into fixing them just because he wears a sheriff star on his breast. His loyalty can no longer excuse his selfishness.

You have no idea how refreshing this development is—especially after binging all eight canonical Toy Story chapters before settling in for number nine. I’m not saying Woody doesn’t hold altruism as sacred and doesn’t do everything he can to save those less-fortunate than himself. I’m simply explaining that a dissection of the intrinsic privilege he possesses to inhabit a position that allows him to act the savior was long overdue. After years of control and impulsive decisions made without consultation from those by his side, the time has finally come where he’s the new guy and thus the one to shut-up and listen. Does he? Not initially. Jealousy has Woody ignoring toy protocol and willfully disobeying Bonnie’s father to recklessly risk her wellbeing for personal gain.

Here enters the complex duality of his actions. By stowing away in Bonnie’s backpack for her first day of kindergarten, Woody does provide priceless moral support. In the process, however, he also lays the foundation for her manufacturing a crutch—the thing her parents hoped wouldn’t occur by asking her to keep her toys at home. School is for socializing and forging new bonds that an old trusty one might prevent. So instead of having Bonnie confront the boy who takes the art toolbox from her table, Woody procures some for her so she can remain comfortably isolated. It’s on that safe island alone where she ultimately constructs Forky (Tony Hale) from bits of trash as a security blanket within the unfamiliar terrain of the classroom.

A spork with pipe cleaner arms and mismatched googly eyes, Forky begs the philosophical question surrounding any object: When does one person’s treasure become another’s trash? Is Forky garbage because he accepted his disposability or a toy because Bonnie wrote her name on his Popsicle stick feet to declare it so? Where does ownership start and autonomy end? When does he get to decide what’s best for him regardless of Woody’s attempts to teach him that his duty is to serve Bonnie’s needs? The Round-up Gang’s leader has spent so long integrating newcomers into his child’s tribe (“the noblest act any toy can perform is to grant fealty to the boy or girl that loves it”) that he’s brainwashed himself into believing he doesn’t matter outside that role.

Forky jumping out the window of Bonnie’s family’s RV miles outside a campsite carnival therefore sparks an adventure as well as compels Woody to question everything he’s ever known. The thing this cowboy has feared his entire existence becomes a choice he can make rather than one that’s made for him. While Jessie (Joan Cusack) was left in a donation box and Lots-o’-Huggin’ Bear abandoned and replaced, Forky has the love of a child that ensures those things won’t happen to him and yet he rejects it. This is a head-explosion-type revelation with adult themes of liberty, self-improvement, and empowerment explicitly brought to the fore of a franchise otherwise built-upon servitude above independence. Woody loves his life because he’s the golden goose. Not everyone is so lucky.

Gabby Gabby (Christina Hendricks) was born with a defective voice box and thus unable to receive the love so many of her model had. Bunny (Jordan Peele) and Ducky (Keegan-Michael Key) are prizes for an impossible game of chance who spent years getting to a spot with visibility in the hopes a child lucks into winning them. And Bo Peep is serendipitously found living untethered in this sleepy town with a joyous outlook on life she never found while in a human’s care. She might not have chosen to be discarded, but she did choose to remain free to fend for herself and help other orphan toys grow thick skins in the outside world (Keanu Reeves’ Canadian stunt-toy Duke Caboom still spirals when thinking about his beloved former owner).

What’s to be done, then, when Forky is held hostage by Gabby Gabby and her army of creepy ventriloquist dummies named Benson? Obviously Woody’s instinct is to save him by any means necessary, but can that urge be quelled enough to do so smartly? He’ll need to trust Bo as the person who knows his enemy’s terrain best and also swallow his pride when his impetuousness puts everyone he loves in danger. And when he does neither, he’ll have to experience the shame he’s desperately tried to ignore. Because as is inferred throughout the film, Woody has been lost. While those “lost” in the physical sense of the word are revealed to know exactly who and where they are, he cannot cope with his newfound status far-removed from the top.

It took two-and-a-half decades, but the symbiotic nature between toy and child has finally been augmented to break this world’s possibilities wide open while also opening the door for real emotional hardship on an individual level besides the communal one. Everyone must still make sacrifices for the greater good (Duke, Bunny, and Ducky are hilariously irreverent additions to do so), but that goal is for the betterment of all toys rather than one owner’s. A life lived no longer ends because someone demands it. Retirement is no longer a toy’s only choice. Woody broke the rules in first Toy Story to save lives and many characters here follow suit. At a certain point those with privilege must let those without live as though they do.

That lesson couldn’t be more attuned to the world in which we live today. While the series has flirted with non-binary decisions (Toy Story 2 had Woody wrestling with returning to Andy or saving Jessie and Bullseye from eternal storage), never before have the stakes been this complicated. The fear being confronted here is life-or-death of a psychological sort that proves just as painfully debilitating as facing a garbage dump’s incinerator. Bo Peep can fondly remember her role in shaping young Molly’s life while also refusing to regret her decision to never put herself in that position again. She’s allowed happiness too. Loyalty should never be at the detriment of one’s own wellbeing whether in a personal or professional relationship. Service isn’t slavery and individuality isn’t a liability.

Toy Story 4 is now in wide release.