“Today is the 5th of November. But I can’t really know if today is the 5th of November… I doubt which time is very important.” This line of narration, echoing the famous backtracking introduction of Camus’ The Stranger, is the austere and ominous opening of Julian Roman Pölsler’s The Wall.

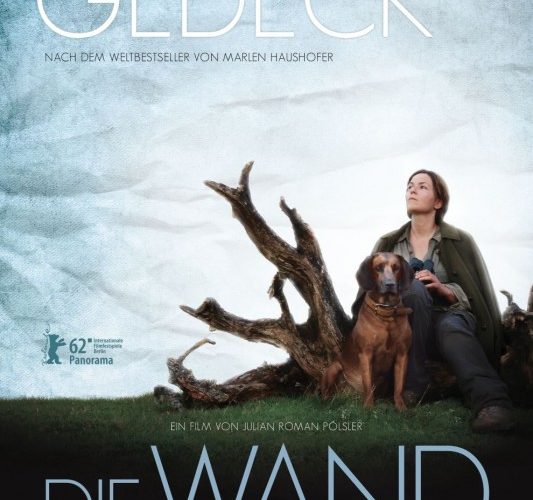

It is spoken by the Woman (Martina Gedeck), who is seen occupying a cabin in the middle of a postcard perfect Alpine wilderness vigorously composing her memoir, which she believes to be the last testament of any human on the planet Earth. How she came to be here is no mystery; she traveled with an older couple who went into town and never returned, but why she cannot leave is the unusual speculative concept that drives the drama. In Pölsler’s clever visualization of Marlen Haushofer’s 1963 novel, an invisible wall, that reverberates sound thanks to some stunning audio design, encloses the woman in a kind of naturalist snow globe. She can see vehicles and people on the other side of this impediment, but her existence is cloistered; it’s just she, the animals around her and the silent valley.

How far the barrier lies and what it is exactly are never made specifically clear. This is a purposeful tactic of both the novel and the movie, eschewing blatant science fiction in favor of something more ruminative and aesthetically poetic. What the wall stirs in the Woman is the primary focus of Pölsler’s film; we witness how it isolates her from her society and pushes her towards the natural world, creating a tug within her own fundamental nature. Left to establish survival in her strange exile, the woman turns to agriculture (hay and potatoes) and adopts the company of a small group of domesticated animals; a vigilant dog, a couple of cats and a pregnant but endearing cow.

The seasons pass in visual splendor—the limits of this vast and pristine woodland encompassing both rustic joy and existential lonesomeness—and all the while, the Woman ceaselessly narrates, underscoring Pölsler’s lovely silent saga with chatter intended to expose the protagonist’s spiritual quest. The wall itself ceases to be of much consequence, only important to draw lines between the inner and outer realms of the Woman’s consciousness. Eventually, the civilized environ she left behind finds a way to puncture her new enlightenment, and her pact with the natural way of things threatens to unravel. The narrative structure moves back and forth, oscillating time frames, but more importantly shifting between two divisive world views that struggle within the Woman herself. What is an often breathtaking and patiently expressive survival story is marred around the edges by that ever-present voice on the soundtrack, which prevents us from ever truly sharing the Woman’s experience by inundating us with her every thought.

Despite his failings with a needlessly wordy screenplay, Pölsler creates a deeply engaging sensory journey that also doubles as an invigorating post-apocalyptic vision; one of the very few of its kind that successfully divorces the social ramifications of man from the equation and gives us a jaunt into a world defaulted to the factory settings. The film itself is carried by the richly textured acting of the lovely and distinctive Gedeck, who tears away the handsomely illustrated metaphorical veneer and makes The Wall its own kind of riveting adventure. There’s a touching and inspiring majesty applied to the Austrian setting, and in its way Pölsler’s film is as immediate and as titillating to the senses as this year’s Kon Tiki, another tale of mankind pushing through nature’s boundaries to discover ancient instincts. Like the best of Malick, classical music entwines itself with displays of Earthly creation.

Now, we arrive back at the science fiction, which, in the end, isn’t as completely dismissed as it seems. There are no specific genre traits to be found, but there is a kind of magical realism at play, recalling stranger, more dour work like The Turin Horse or Tarkovsky’s Stalker. There’s also an interesting distinction; even when considering more universal quandaries like the essence of a human nature, the movie expresses a predominantly female viewpoint. Through this lens, the inhibiting confines of the invisible barricade take on a familiar shape.

The Wall shares some spiritual DNA with Shane Carruth’s Upstream Color , and like that film it gently redefines what the genre can aspire to be. I was ultimately moved by Gedeck’s performance and exhilarated by the boldness of the images. If Pölsler had trusted their power and toned down the exposition, we might have had a legitimate classic on our hands. Still, there are certainly more haunting things to be found in the long solitary looks Gedeck casts towards the audience than in any of the dozens of special effects skirmishes we have witnessed this year.

The Wall opens in limited release on May 31st.