There have been countless renditions of Romeo and Juliet during the past five hundred or so years and yet its themes still haven’t grown stale. Bentley Dean and Martin Butler‘s Tanna isn’t an official retelling considering its tale is based on a real-life romance, but it’s nearly impossible not to think about the Shakespearian classic while watching. The events onscreen occurred in 1987 in the midst of civil unrest between two tribes of the Kastom roads. With colonialists and Christians arriving at their Vanuatuan island to convert natives to their ways, a few inhabitants stayed devoted to the ancient traditions. Despite their common lifestyle, however, tensions remained via a struggle for land. And like European wars centuries ago, the surest way to stop the bloodshed was marriage.

Before Dean and Butler reveal this hopeful alliance, though, we must become acquainted with the Yakel people. The actors are ostensibly playing themselves with roles taken from history projected upon them. It’s therefore less a performance that we witness and more an unfiltered way of life as the focus falls upon sisters Wawa (Marie Wawa) and Selin (Marceline Rofit), the former readying for her ceremony towards womanhood and the latter precociously shirking her elders for youthful fun and adventure. It’s through them that we ultimately learn about Yakel culture and the hierarchy within their tribe. Their grandfather is shaman (Albi Nangia), their parents respected members of the community (Lingai Kowia and Linette Yowayin) playing their respective parts. Both girls will soon find their own place in this society.

The activities shown are steeped in ritual and therefore caught between old and new generational thinking. Because while we watch Wawa’s grandmother (Dadwa Mungau) lead the other women in preparations for the girl’s inevitable arrangement, it’s not difficult to see where her true intentions lie. Despite the tribe’s needs from both, Wawa is very much in love with Dain (Mungau Dain), the grandson of their Chief (Chief Charlie Kahla). But he is in line to be their next leader and therefore perfectly placed as a suitor to an outsider rather than one from within. And she is the latest daughter of childbearing age, a prize for any outsider to deliver peace in return. Maybe things will still work out. Maybe peace will hold until others take their place.

Unfortunately life isn’t so forgiving as we catch the gaze of Kapan Cook, a member of the Imedin tribe, watching Selin and her grandfather’s journey to the volcano Yahul. He’s the son of his Chief (Chief Mikum Tainakou), a man who’s allowed violence to dictate their relationships for too long. With one attack the men on both sides grow anxious for war. Their Peacemaking Chief (Chief Mungau Yokay) hopes to instill calm and stop the cycle of bloody vengeance—the nuptials of Wawa and Cook a logical solution. With additional baggage thanks to the acrimonious dynamic between tribes weighing heavy above this decision, Dain does the unthinkable by not letting love become secondary to communal harmony. And in a world where one wrong step spells disaster, he steps hard.

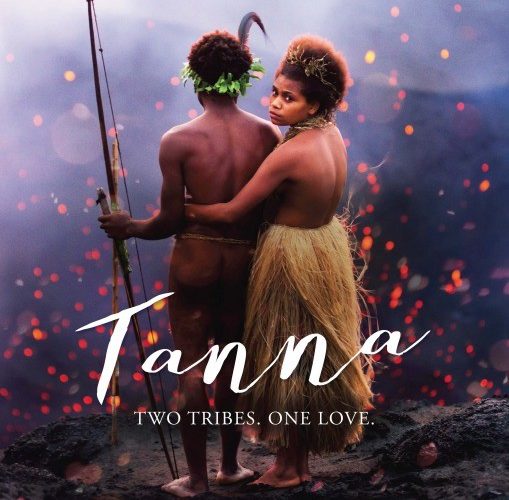

It’s a familiar tale pitting selfish desire against the greater good, but it’s like nothing you’ve ever seen thanks to the wondrous South Pacific landscapes. There are fireworks spewing out of Yahul—the orange lava glowing against the dark night sky—as the massive sense of scale between characters and mountains create awe-inspiring visuals not to be forgotten. It’s not just nature either, though, as the joyous escapades of Selin and the other children instill an unbridled atmosphere of fun while the adult women engage in their own dance when weaving fresh skirts for impending celebrations. From the painted faces to the carefully pocked leaves in Dain’s headdress, the level of detail is nothing short of spectacular. Its authenticity may make you forget you aren’t watching a documentary.

And yet it almost is one, its story of progress infiltrating the Kastom ways without dismantling its essence a tough but hopeful step forward. Wawa and Dain’s love recalls one that threatened to destroy an entire way of life, its power able to move mountains despite conjuring a danger that would never let them stop looking over shoulders. With its progression highlighting Selin as a voyeur who must choose between sister and tribe or the looming forests marked as taboo with enemies lurking in the shadows, my mind began thinking of Atonement and The Village to temper the Romeo and Juliet notions of forbidden love. The idea of finding your identity from within despite residing inside a culture built on forcing one upon you will never cease resonating.

To also witness an unfamiliar people in these complexities is a testament to cinema’s ability to open eyes to new worlds. Dean and Butler shot on location with pre-production and production lasting over half a year. By retaining the native languages (Nauvhal and Nafe) and seeking a collaboration with the Yakel people, a sense of local realism is left intact to deliver an uncensored view to newcomers while also immortalizing a tale that has forever reshaped who they are. It’s never about belittling Kastom traditions or labeling them archaic either as Christianity is still included as a way out for which these lovers refuse to take. They aren’t forsaking their religion or customs as much as acknowledging their feelings above them. If they could have both, they would.

Before real change occurs, however, sacrifices must be made. Compromise is always possible, but it comes at a price. Chiefs are reminded that the Earth keeps spinning while evolutionary thinking renders people harder to control. It’s not necessarily an idea of disrespect that motivates Selin, Wawa, or Dain. They merely crave what their hearts desire. They love their parents and way of life, but wish it would allow them to be individuals as well as integral cogs within its ancient system. Selin doesn’t disregard orders because of a rebellious streak; she does so because she knows her value to the mission at-hand outweighs her youth. Wawa and Dain don’t go off together because they hope war comes; they do it because they wouldn’t be able to live otherwise.

Tanna is currently available on digital platforms with a DVD/Blu-Ray release on March 7th.