I love Banksy‘s work most because of how it comments on the commodification of art. Here’s a world-renowned master who refuses to authenticate anything he’s done on the street—his canvas of choice. He does this as a stand for the form, for what graffiti has always been. The pieces he stencils are site-specific both in the sense of the wall and the country for which he’s commenting politically. They are simultaneously powerful and fleeting. They strike a chord internationally, spark conversation, provide a sense of awe and celebrity, and then disappear. Others tag over them. Owners cover them with paint. And both are okay considering they aren’t meant to be permanent. It’s less about beauty and aesthetics than emotion and context. They’re rendered immortal by their deaths.

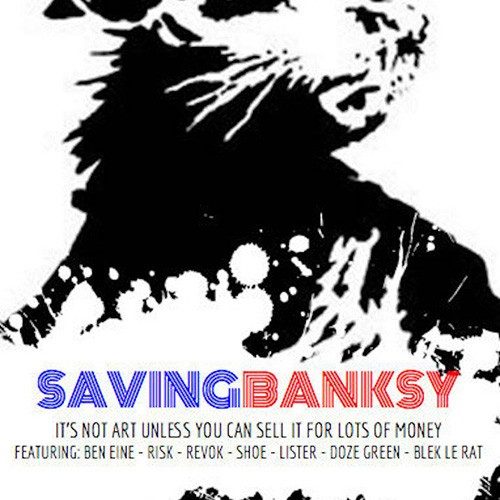

Director Colin M. Day‘s documentary Saving Banksy seeks to approach the notion of artistic intent by showcasing Banksy’s contemporaries, opportunists stealing their work to make a buck, and one man doing his best to remain true to the work and himself along a journey to preserve what was never meant to be preserved. The project began as a way to document the wild time in San Francisco history when Britain’s favorite “criminal” visited with spray can in hand. April 2010 saw six works pop up during a one-week period, some of which were destroyed within 48-hours of being seen. Day filmed the city reconciling the duality of each piece as vandalism and art, meeting Brian Greif—a collector hell-bent on saving one for the people—along the way.

The film’s motives shift as the real story becomes how our capitalist society deals with objects of fluctuating worth devoid of utility beyond emotional impact. Day interviews numerous artists with one standing out: Ben Eine. Not only an important participant in the graffiti movement as an artist working illegally in the streets and legally in the studio, he’s also a personal friend of Banksy’s. He’s able to therefore generally contextualize work created in a public place that should be destroyed before ever hanging on a collector’s wall, and more specifically about the mysterious figure who’s celebrity has completely changed the conversation of street art’s legitimacy. Eine’s best characteristic, however, is his honesty to acknowledge it might be nice in fifty years to know one of his works survived.

This brings us to Greif’s complex quest to do something for the community at personal financial cost. Only a couple San Francisco pieces remained untouched when the idea to extricate one came to him, the star-capped rat drawing “the line” proving the most attractive and feasible. Wanting to preserve this gift to the city would be a welcome decision in a utopia, but America isn’t that. What follows is instead a race against time to finagle deals before certain parties are aware of the work’s worth. It becomes a feat of patience to wade through extortion attempts, city interference, and art world morals. And that should be the hard part considering every gallery in the world would jump at the chance of owning a Banksy for free. Right?

Nothing could be further from the truth as arts brokers like Stephan Keszler have made showing Banksy’s work in a gallery impossible. A man shone as the kind of person that would sell his grandmother for the right price, Keszler’s bolstered his career by condoning the cutting out of public art to be sold for commission. He knows millionaires will pay top dollar to have a five-ton slab of concrete put in their mansions simply because of the name “Banksy.” None of the profits go to the artist and what might have been viewed in the streets for another day before destruction is never to be seen again. Is it better to witness the remnants of a masterpiece ruined or to know it exists behind lock and key?

Banksy wants the former. He won’t authenticate anything because vultures profit from it. He documents what he does with photography and places them on his website to earn digital immortality. But they also live forever in the minds of those who saw them first-hand. His messages are potent and unforgettable; the place they’re installed as crucial to their meaning as the words and iconography itself. If he wanted them to hang on a wall he’d have painted them on canvas, called his agent, and watched the bidding war. All these artists have art to sell and art to exist. So while it’s easy to hear Keszler talk about not needing permission to sell what the creator didn’t have permission to create, he’s still ethically a black market dealer.

This is an issue that we need to look at in the twenty-first century. We need to approach laws differently than we did whether it be jail time for graffiti, preservation of public works, or the way art is morphed by tastemakers and curators who may or may not be bought and sold. If Banksy was working in a world without Keszlers, he might rethink his authentication protocol (there would still be issues about his art being illegal). Signing a piece of paper that lets a museum put a work on their walls might not be used as evidence to arrest him if/when his identity is ever revealed. He would even have the ability to say, “No.” That piece was conceived for one arena and one arena only.

It’s a complicated issue that Saving Banksy introduces to the public consciousness. Where the movie struggles is balancing that central plot with other peripheral notions. I feel like Day could have made three documentaries out of his footage: one about Greif’s journey, one about street artists, and one about the art world’s old and new guard. I enjoyed hearing artists express frustration towards museums refusing Greif’s piece while those curators counter with airtight cases as to why. Unless an artist wants his/her piece displayed out of context, doing so is a disservice to the work. Many great debates like this are presented without time to dive deeper, a fact making Day’s film a wonderful prologue to all despite preventing it from being an essential thesis on any one.

Saving Banksy is now in limited release.