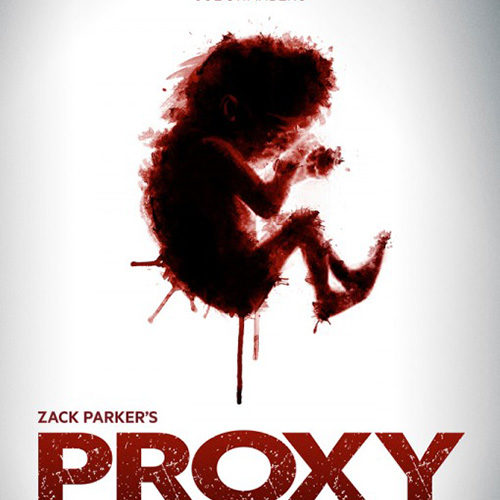

I learned something while watching Zack Parker‘s horror (though psychological thriller is a more apt genre label) film Proxy: Richmond, Indiana is a hotbed for crazy. He and cowriter Kevin Donner inject a little Münchausen syndrome, Prenatal Depression, and some run-of-the-mill psychopathy to round out the quartet of main characters. Each seemingly normal on the surface until a chaotic mind or the potential for psychotic break under tragic circumstances is exposed thanks to carefully unfolding revelations, the people populating this tale are regular folk hiding dark secrets. The film latches onto the phenomenon that always finds the acquaintances of killers telling news reporters how he/she was “the nicest person.” I guess we all are until we’re not and Parker is admirably unafraid to admit it by letting his cast become unsuspecting monsters partaking in heinous crimes.

I wonder, however, whether his thesis on the subject needed to be over two-hours long. To some this fact might be a good thing as those long quiet shots of actors walking down corridors while The Newton Brothers‘ score blares its faux subtlety works to get their hearts racing. I’m sadly not inclined to agree. Instead I could only think about another “horror” film I believed held promise sight unseen before discovering its laborious journey bereft of anything I would call suspense: What Lies Beneath. You can see every moment that is supposed to put you on the edge of your seat, but each ends up lasting way too long until curiosity turns to frustration and all mystery is flipped on its head with a concrete answer to remove all semblance of ambiguity.

I like where the director’s head is at as far as wanting to create something fresh, though. When he speaks about a desire to push the boundaries of storytelling and make his audience think about what they’re watching, you believe those motivations and know he strove to meet them. Unfortunately, while two scenes effectively give a glimpse into the warped minds brought to life, quick explanations of them being hallucinations ruins the sense of doubt he hoped to instill. That’s not to say he shouldn’t have defined them—one needs to expose the truth at least once for audiences to accept the possibility of deceit. But the rest must in turn remain shrouded in the unknown. It’s as though he wanted to be subtle but couldn’t help himself from creating an air of trashy, borderline comedy as well.

This is where Proxy falls apart. Whether it’s following our lead Esther (Alexia Rasmussen) after a brutal attack leaves her disfigured and her two-weeks-from-delivery fetus dead; learning the complexities of Melanie (Alexa Havins), a friend Esther meets at a support group for grieving parents; witnessing the mental break of a father who cannot let go of the anger his son’s senseless murder instills (Joe Swanberg‘s Patrick); or meeting Esther’s violently jealous girlfriend Anika (Kristina Klebe) in varying states of rage, everything but the aforementioned blatant examples of fantasy is explained. So each time Parker and Donner force us to give pause and ask if everything that came before was real, it doesn’t take long to realize the plot could only have progressed where it does if the answer is yes.

It doesn’t help that the film is overly long, has its vantage point changed too often, and proves more confusing than entertaining. I applaud the filmmakers for refusing to stick to a logline that really only describes the first thirty minutes of its two-hour length, but that ambition is never quite brought to fruition. Every time I thought things were getting better, the fun of guessing is replaced by solutions so we may move onto the next mystery. While this can be a successful maneuver when done right, it gives Proxy a stilted rhythm that never allows the previous puzzle’s closure to be satisfying or the current one’s question intriguing. The transitions force us onto a plot progression we’re never ready for, giving us a checklist to move onto the next character rather than a seamless evolution.

Think The Place Beyond the Pines with psychological distress providing connective tissue rather than Derek Cianfrance‘s socio-economical commentary. Where Pines‘ triptych gave us an in-depth look at the why, though, Proxy seems content just giving a series of bloody climaxes. Parker and Donner have manufactured this chain of events in a way that makes every tragedy somewhat the fault of the victim—something I really enjoyed—but it glosses over the bigger picture. I want to delve into Esther’s psychology and discover why she’s so despondent about her pregnancy at the start and why she’s such a loner. I want to see the circumstances that led Melanie to become so unhinged a liar that she can no longer comprehend the difference between reality and imagination. The violence resulting from their instability is cheap without such explanation.

Rasmussen and Havins are both wonderful at switching back and forth from kindhearted compassion to selfishly motivated bringers of destruction. We believe in their complexity and simultaneously sympathize with their plight while reviling their actions. Swanberg earns this to a certain extent also when the focus shifts his way, but the spotlight is all too brief to fully realize his descent. And despite Klebe being their entertaining contrast (she’s the only character fully cognizant of her behavior), her interludes are hard to see as anything but comic relief. As a result, Proxy might have been great if it stuck to either its introspective exposé of the human condition or its schlocky gore. Attempting both never quite works—a failure that somehow makes it feel rushed and boring by not allowing us to understand anyone onscreen beyond their two-dimensional darkness.

Proxy is now available on VOD and opens in limited release on Friday, April 18th.