When someone kills seventeen people over a thirteen-year span with words like necrophilia and cannibalism circling each murder, sympathy for the predator — not his prey — is neither the first nor hundredth emotion that should come to anyone’s mind. I’m not certain there could be room for anything but disgust whether you’re a stranger, a family member, or an old friend reading the news. And yet we try to find motivation nonetheless. We wonder about how someone could become such a monster right under our nose without ever suspecting it. There’s this unavoidable sense of morbid fascination because we can’t fathom doing what he’s done. The need to therefore discover what in his life drove him to that point trumps everything. We seek reason in the unreasonable.

While it’s one thing to live vicariously through the nonsensical ravings and actions of a D-list wannabe celebrity who stumbled drunkenly into a reality TV show, it’s another to get into the mind of a homicidal maniac. So many of us do it, though — especially today in a post-“Serial” world. As darkness and carnage earns ad clicks, the venues plying them multiply in order to reap the benefits. But at some point these deep dives into crimes move beyond the idea that someone may be falsely accused or a cold case could be solved years later. The line separating a constructive use of time/resources and the salacious commoditization of the macabre will inevitably blur. Rather than search for answers, we merely end up glorifying the infamous with prestige.

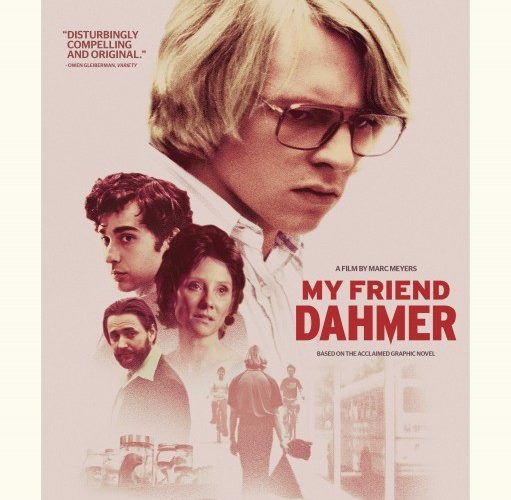

I can’t speak to the graphic novel, but Marc Meyers’ cinematic adaptation of My Friend Dahmer does the latter. The concept alone is misguided on paper because it declares that events led Jeffrey Dahmer to do what he did. It supposes that something could have been done to stop him and everyone blind to the signs is culpable. This is a dangerous thought because it humanizes what relinquished his right to be human. It minimizes the tragedy of those who died by his hands and makes a mockery of psychopathy by eschewing its nuance for blatant earmarks of trouble. What’s even worse, however, is that this film makes it seem as though author (and “friend”) Derf Backderf isn’t looking for answers. He’s desperately trying to assuage his guilt.

The story goes that Derf found out about Dahmer’s arrest from his wife, a journalist. She called him up and said that someone he graduated with was a serial killer and jokingly asked who he thought it was. Supposedly Dahmer wasn’t his first guess. Supposedly we’re to believe this because he befriended the loner during their senior year of high school and thus cultivated a kinship able to shroud the objective truth in inherent nostalgia-based subjectivity. This is a cool concept and one worthy of elaboration because it puts the onus on Derf as a storyteller to show how a soon-to-be killer could be considered “normal” via a skewed memory. And maybe his book does that. Maybe his personal look back provides context the film assuredly does not.

From the opening frame we dismiss Jeffrey (Ross Lynch) as a complete freak anyone with a brain would question. I’m not talking about actions either. His wanting to “see how things look on the inside” is weird, but not necessarily insane considering Dahmer enjoys biology and hopes to study it in college. Using his dad’s (Dallas Roberts) acid to melt the skin off of road-kill should be the obvious problem and yet even it isn’t. What I couldn’t stop staring at was Lynch’s demeanor: his empty eyes, whispered voice when not absolutely silent, and stiff walk with motionless arms hunched forward as though he was a caricature of suffering. His Dahmer is one colored by the knowledge of what he becomes, not the innocent so many absentmindedly believed.

Whether that’s how he was or not, it ensures we’ll never give him the benefit of the doubt. We’ll never wonder, “Oh, man. If his mother (Anne Heche) wasn’t clinically insane and his parents didn’t divorce and his ‘friends’ didn’t treat him like a sideshow prop to be their jester, maybe he would have been alright.” No. Meyers doesn’t provide that out and as a result forces us to question his goal for bringing this story to the big screen. If we’re not supposed to pity Dahmer while watching the unfortunate progression of his sad life, why are we watching? Is it to reinforce the notion that he was always a monster? Or is it to forgive Derf (Alex Wolff) and his buds for assisting in his descent?

In the end it really doesn’t matter because we don’t buy any of it. We simply watch with sadness and marvel at how bad Derf draws himself and his BFFs (Tommy Nelson’s remorseful Neil and Harrison Holzer’s opportunist Mike). They are the monsters of this tale, their easy laughter as Dahmer turns from invisible wallflower to warped class clown through the offensive act of “spazzing” like someone with palsy shows their immaturity and utter lack of humanity. They barter paper-thin popularity and their own fickle loyalty for a few cheap laughs and Jeffrey performs. He must because his father already shattered the ability to do the one thing he enjoys in order to vicariously chase a life of friendship and activity he himself rejected in his own youth.

Add rampant homophobia and you wonder if the filmmakers are saying that all bullied, closeted gays are prone to snapping badly enough to murder in cold blood and eat their victims’ flesh. Rather than hone in on the contextually relevant aspects of Jeffrey’s demeanor like his asking the sole black kid at his school if he thinks their organs are the same color even though their skin isn’t, we’re made to endure the constant physical and verbal abuse of gay classmate Oliver (Jack DeVillers). And the way Jeffrey tries to both befriend him and ignore him when it suits his own wellbeing mixed with Oliver’s resignation to the beatings as though they’re simply a way of life plays as though we should be laughing. It’s not remotely funny.

The only thing funny about My Friend Dahmer is the over-the-top yearning for forgiveness on the part of Derf. The line “Oh, we were just having fun” is such a perfect cop-out, one with a level of authenticity very little of what we see otherwise possesses. It admits that he did nothing to help Jeffrey’s depressed soul. It admits he was never his friend. But no matter how much the audience wants to blame him, we don’t. We don’t blame his mother’s crazy, Dad’s selfish ambivalence, or Jeffrey’s embarrassment about being sexually attracted to men either. We don’t because the film tries too hard. All that is so overt that it renders Dahmer a two-dimensional afterthought in the process. We watch the cruelty of adolescence and learn nothing.

My Friend Dahmer opens in limited release on Friday, November 3.