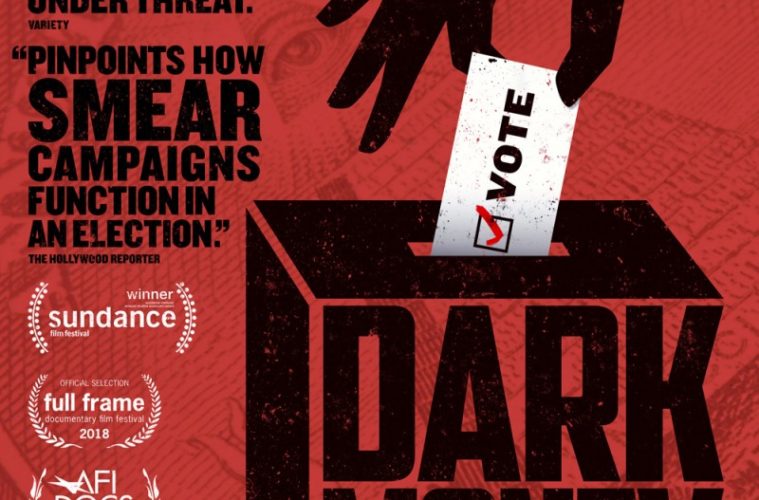

Campaign finance is a phrase that lingers on the fringes of most political conservations, though rarely the center of focus. Dark Money, directed by Kimberly Reed, aims to change that. As Ann Ravel, Chair of the Federal Election Commission (FEC), states: “Campaign finance is like the gateway issue to every other issue you might care about.” Fast and furious in its information and interviews, this documentary is engaging from minute one, rarely letting the viewer off the hook.

The action here is set in Montana, a large state with a small-town vibe. Over a century ago, the city of Butte became a haven for copper mining and big industry capital. Specifically, the eventual monopoly of the Anaconda Copper Company. What resulted was environmental disaster allowed through systemic corruption within the state government. Thousands of human lives lost, along with thousands of animal lives. The people of Montana reacted to this by putting into place regulations to prevent powerful companies from buying seats in government. Then, in 2010, the Supreme Court decided on Citizens United v. FEC, deeming regulatory measures on spending in campaign finance unlawful. How states can combat against this federal ruling is still something being determined across the country.

What’s resulted in places like Montana is an influx of “dark money,” a term that defines the process in which corporations donate to non-profit organizations that exist solely to fund specific campaigns. Reed explores the effects this kind of cash has had in recent Montana politics, while attempting to follow the money back to its original source. It’s a fascinating (and concerning) investigation and Reed does well in presenting multiple angles of where the influence lands and how it bleeds into the local and, ultimately, national politics. The conduit for much of this research is John Adams, an investigative journalist diving down the rabbit hole of dark money. Whether it’s an overflow of flyers falsely tying candidates to evil elements of society (former rep. John Ward tells a heck of a tale early on in the film) or former State Representative Art Wittich and his illegal connection to the National Right to Work Committee through the non-profit American Tradition Partnership, Reed highlights the corruption clearly and competently.

At 97 minutes, Dark Money is a focused piece of work that wears its agenda proudly on its sleeve. That being said, the facts presented feel indisputable, as facts should be. Adams emerges as a worthy subject to follow, a tireless journalist who keeps working even when those publications he works for dismiss him. His noble pursuits echo that of some of the politicians Reed puts on camera: humble men and women who carry on day jobs while representing their state of Montana in Congress. There is a truth presented in this film that is hard to deny. Freedom of speech is vital to the idea of America and of the American individual. But in extending that right to corporate interests, we risk stealing an individual’s ability to choose what kind of politics they want to support.

Dark Money is now in limited release and will expand in the coming weeks.