I never had the chance to attend New York City’s CBGB, “the birthplace of punk,” but if my first exposure to it were the film of the same name, I’m not sure I would want to.

CBGB is largely devoid of any of the context which actually made punk matter and which actually made the titular club important, and its best moments are, without question, performance scenes that use the master tracks of songs from The Velvet Underground, The Ramones, The Dead Boys, and Talking Heads. The film begins with two characters, in a basement, who decide to start Punk Magazine, making for a curious start to a film that has very, very little to do with Punk Magazine. Its biggest contribution is providing CBGB with an aesthetic and structure, which is itself modeled after a comic book — including frequent digital zooms out before re-entering on a different panel, often with Batman-style onomatopoeia to go along. Unfortunately, this contribution is more a distraction than a hand-drawn reflection of punk’s DIY aesthetic, all of which is entirely absent.

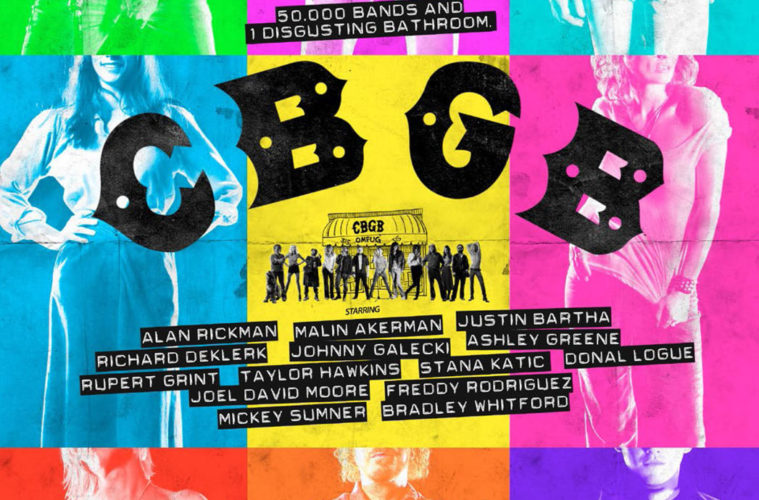

When CBGB proper begins — after about a dozen title cards or character indicators in less than as many minutes — Hilly Kristal (Alan Rickman) is starting up his third club with the intention of booking country, bluegrass, and blues bands to play (hence the initials in the name). It doesn’t take long before Television shows up instead, and, one “Marquee Moon” performance later, the Village Voice has turned it into the hottest place in town. It’s hard to say if director / co-writer Randall Miller and co-writer Jody Savin are more concerned with replicating performances by punk legends or following Hilly’s attempt to keep the club afloat, but it seems to lean toward the latter. With help from some buddies and his reluctant daughter, Lisa (Ashley Greene) — the film’s only intelligent character — Hilly almost manages to do so.

Aside from how bad many of the performances are — particularly actors who play musicians; Kyle Gallner‘s portrayal of Lou Reed might initiate a walk-out among the most devoted — what’s so infuriating about CBGB is how utterly uninteresting Miller and Savin make their story, which is already lifted from 24 Hour Party People to begin with. The most recursive elements throughout are people stepping in dog feces and the filthiness of the CBGB’s bathroom, two gags which seem included purely to wink at the viewers “in the know.” (Comic relief is a possibility, but then we have to ask “how is this funny?” and “relief from what?”) Hilly is devoid of inspiration, intelligence, and motivation of any kind, to the point where he comes across as an idiot who chanced into something great and nearly ruined it.

Each time a problem arises — nobody likes his club, he can’t pay rent, he wants to manage a band — everything is resolved in mere minutes, almost always because of Lisa, and thus any sense of drama, tension, or character growth is completely avoided. If CBGB wants to tell the false and simple story of a dumb guy who chanced his way into punk royalty, at least it would be a commitment to something; instead, the film begs us to worship Hilly’s coolness and bravery while pitying his poor business sense, but gives us no legitimate reason to do so. It’s abundantly clear that the Hilly from any point throughout would act the same way as Hilly at any other point, in all situations. In fact, it’s impossible to find any character in CBGB who could be described with three adjectives aside from physical notices.

With characters tossed to the wayside, Miller and Savin could at least focus on showing us why CBGB is important, but almost the entire film takes place inside or just outside the club, which, save for a line of dialogue or two, seems like it’s the entire world. There is no New York for us to place CBGB in; bands seem to just float into the next introduction scene, as if the audience is supposed to be checking off a list to ensure that every cool group who played there gets mentioned. Any deviation from the formula — Hilly has a problem; Hilly makes a bad decision; Lisa fixes it; Hilly doesn’t appreciate it, but Lisa comes back, anyway — is even worse than the formula. A recurring joke about the chili, which is made with 15 squirts of ketchup, not only misses the first time, but gets worse and more forced from there.

Hilly’s attempt to manage The Dead Boys adds absolutely nothing to CBGB, except to show his character lose money. Occasional cutaways to the founders of Punk Magazine and their first writer talking about punk reads like a list of clichés spurted out at the last minute with no explanation to go along, and no actual relation to the performances we are regularly treated to. These are, often, excuses to create a montage linked together by the comic book structure, but never does this framing device actually mean anything. And, indeed, the film quickly forgets how it began, abandoning the flashback-heavy, title card-reliant structure that at least made it feel like a comic book.

With nonexistent character depth, abysmal storytelling, and an aesthetic gimmick that hurts the film far more than it helps, it is not an exaggeration to say that all CBGB has to its benefit is a killer soundtrack — and the music is the only thing which ever suggests CBGB was an original or relevant location. And, yet, the distracting casting takes away from the music, leaving very, very little, more likely to turn off newcomers than draw them in. With works like Please Kill Me and Our Band Could Be Your Life — two novels that give a far more accurate and pleasurable account of one of the most significant music scenes of the post-Beatles era — what is there to gain from CBGB? It’s certainly not entertainment, and it’s most definitely not insight.

CBGB hits theaters on Friday, October 11th.