The inescapable, incompatible bonds between man and machine is an idea which can be traced back to the incipient stages of cinema itself; we may be inclined to think of the Lumière brothers‘ Workers Leaving the Factory or The Sprinkler Sprinkled, though that apocryphal tale of audiences scared witless by images of an oncoming train may, too, seem appropriate. So long as our innumerable systems of modern living continue moving forward with the over-idealized goal of creating better living, we should only expect the medium to exploit their impacts for subject matter time and time again — in slow stages, again and again finding something new to mine from our evolving world.

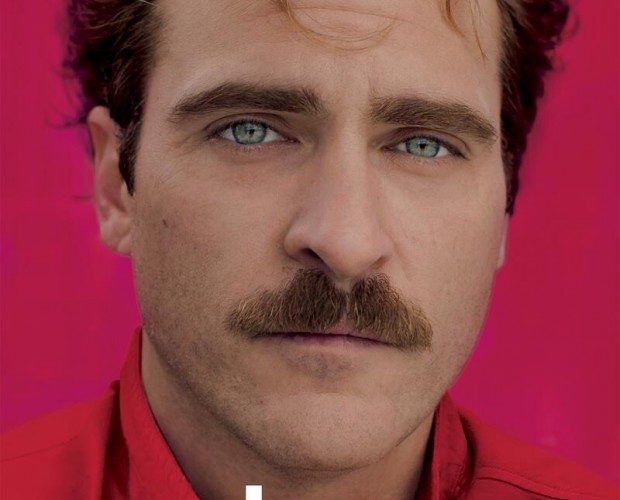

To such an end, it might go without saying that Her, the newest motion picture from Spike Jonze — his first since 2009’s Where the Wild Things Are, a title that was itself seven years out from the Cage v. Cage comedy Adaptation — wouldn’t be the first to approach the ever-prevalent pull human-computer relationships have on human-human interaction, and, given the noted propensity of similar content, it shouldn’t come as a great surprise that this isn’t the finest yet seen. Nevertheless, what we have is, still, among the more pleasurable, immediately satisfying, and appreciably ambivalent of techno-love tales; for being centered on something so curious as the life-improving romance Theodore Twombly (a glasses- and mustache-adorned Joaquin Phoenix) strikes up with his computer’s operating system, Samantha — imagine Siri, but delivered through an ear bud device and with far more personality, vis-à-vis the husky tones of Scarlett Johansson — Her displays a curious aversion to narrative contraction as it moves forward, nor once feels inclined to cater while, at once, demanding our collective submission to many, many, many whims.

Although Her lacks any direct suggestions of a time — while barely managing to acknowledge its own place — as early as the second or third shot are we slowly, calmly integrated into a tale of the near-future. (Perhaps 2025 or so, though such a designation is somewhat dependent on how positive you, personally, may feel about human ingenuity.) From the silent placement stems an entirely unanticipated joy, the audience constantly discovering new shapes of this world sans any perfunctory world-building — Twombly’s occupation as a voice-mandated love letter-writer; digital punch-out machines; a Minority Report-esque screen that displays a misogynistic video game; another misogynistic video game, this one created by a supporting character; TV systems that resemble what Apple might break out in a few years’ time — while there’s the occasional perception that Jonze, in his first solo feature screenplay, has a more-necessary-than-appropriate dependance on it to make the whole picture sing.

This sense of control in full effect, little of Her should be considered particularly difficult to ascertain or sort through, but an increasingly intimate relationship between Phoenix’s Twombly and the voice of Johansson’s Samantha, this film’s very heart, remains at the same baffling distance, even as every surrounding piece — shooting, editing, scoring, and scripting that reaches down to the basics of a character arc — would suggest something to be taken at face-value. Herein the gap between ironic observation and earnest embrace rests, barely glancing toward either polarity until Her reveals itself a subversively sweet tale of outfitting mental illnesses to suit others.

But these sometimes-gilded entrances into a more complicated, altogether sadder realm need not imply a weighty experience; pure, unfiltered pleasures abound, sometimes more forcefully through images than words. Even when using its distanced world as a tool for melancholic representation, I could have simply stared at Her all day: Jonze employs cinematographer Hoyte van Hoytema (Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy) to give the dystopic utopia an ambiance alternately hazy and sunny — a balance not so much dependent upon the character of a given scene as where Theodore’s personal progression might be at that very moment — while capturing Los Angeles to a degree this writer has never once encountered onscreen; until one too-pointed line of dialogue serves to clarify, I’d honestly presumed the smog-clouded architectural impositions belonged to Shanghai or Beijing. (As Jonze revealed in a post-screening Q & A, segments were filmed in Pudong, a Shanghai district; this is most evident during a moment set around the use of public transit.) It’s all so inescapable — even the colors that pop (observe Theodore’s jacket in the opening moments, or the panels on walls) never enliven, almost as if inevitably failing to sufficiently exist inside some natural world — that a resort to simulated love is partially justified.

In some indirect accordance with his other NYFF 2013 title, The Immigrant, Phoenix’s turn in Her feels entirely new for the performer, at once playing to the tune of (what we’d perceive as) his director’s every wish while, somehow, imbuing Theodore with the sense of a thespian’s self-possession. Barring full-fledged access to notes on the film’s creation — something which would tarnish its experience, regardless — such queries are moot in the face of the sad, determined, unfortunately relatable final turn.

This is not even to acknowledge that Her is very much a woman’s picture, unquestionably first and foremost with regard to Johansson’s disembodied rendition of Samantha — which, for both the gravity afforded to Phoenix’s work and weight of its own presence, could, in time, prove to be one of the greatest voice performances ever heard. Comparisons are difficult when what we have, here, is a balancing act other work of this strip has so rarely requested. With Her perpetually demanding that we accept artificial intelligence as both a simulated being and authentic person, I’d be flummoxed to hear an argument that, without Johansson’s turn, the film could have maintained its current wavelength. Seemingly aware of a necessary balance between Samantha and Her’s counterparts of the fairer sex, further female protagonists are rightly played as individual pieces of a larger tapestry: Amy Adams, an interstitially-applied lens of sanity; Rooney Mara, predominantly in flashback to Theodore’s more controlled, far happier romantic life; and Olivia Wilde, solely in a brief stretch that, if (and very likely) meant to do no more than encapsulate and justify where the still-young film is headed, is something of a delight.

While undeniably a visual triumph, its aural achievements are slightly more difficult to quantify. The score, composed by Arcade Fire (with contributions from Owen Pallett), is implemented to a surprisingly sparse end, above all else played as a properly airy accompaniment to the visual palette’s dulled colors and the elliptical personal developments of Her’s central protagonist. It’s a delicate, occasionally “pleasant” selection of music, though unlike Win Butler and Régine Chassagne‘s own work for Richard Kelly’s The Box, enaction rings somewhat too softly for us to really notice in any worthwhile way; more overbearing orchestrations are not preferable, needless to say, but why doesn’t a great band’s effort feel as if it’s worth more than a name tag? (For better or for worse, the only moment in which we’d properly detect their distinct touch is during the end credits, in which a haunting excerpt of “Supersymmetry” — the 11-minute-plus closing track on their upcoming Reflektor — gets a final say.) With any luck, Warner Bros. will allow us to explore the full contribution on some ancillary soundtrack; as present, their musical accompaniment is one of the few pieces that contributes little past surface-level significance to Jonze’s man-bot love story, however lightly orchestrated the entire picture may often feel.

We glide through its own ups and downs until Jonze hits a third-act snag, by which point the narrative’s inelegantly episodic quality, once imperceptible, ossifies and protrudes, stagnating the smooth rhythm before hitting an effective, albeit slightly confused finish. As disappointing as it might be for proceedings to settle on a romance so clearly telegraphed from the first onscreen pairing of two particular characters, it’s difficult (if not outright impossible) to fault the thing for reaching an end-point through familiar or, I think, stale methods. If love, never not a confusing sensation, is both inevitable and, yet, never exactly what we’d asked for in the first place, Her gets most of the big details right — and if some genuine connection is ever expected of that nonsensical experience, humans have to contribute a bit of the legwork, too. Computers can only do so much.

Her played at the New York Film Festival, and will open in a limited capacity on December 18; a wide release is expected to begin on January 10.