More than a few eyebrows were raised two years ago when it was announced that the next outing by Bruno Dumont, dour auteur extraordinaire, would be a comedy. But then Li’l Quinquin screened in the Director’s Fortnight and blew everyone away, eventually coming to top Cahiers du Cinéma’s list of the year’s best films. Not only was the four-part miniseries (or four-hour film, per Cahiers) side-splittingly funny, but, surprisingly, it also made perfect sense as a Dumont film. The genre volte-face didn’t require the director to venture into unknown territory — he simply had to push his signature sternness even further to render it hilariously absurd. Hopes were therefore high for Slack Bay, which sees him continue in the same vein. Disappointingly, the film feels like someone trying very hard to imitate Li’l Quinquin, pulling off but a pallid counterfeit.

Dumont constructs most of Slack Bay out of elements lifted from its predecessor: a titular (in the French original) protagonist with a bizarre moniker and a singular physiognomy; a youthful romance between said protagonist and a fair-faced girl (or perhaps boy – more on this in a bit); a bumbling inspector and his constantly bemused subordinate investigating a series of gruesome murders with slapstick ineptitude; secondary, working-class characters, each talking in an impenetrable “C’hti” accent and looking like they were fished out of a Bosch painting; a windswept, Northern French coastal setting captured with glacial beauty; and a meandering narrative that doesn’t lead anywhere.

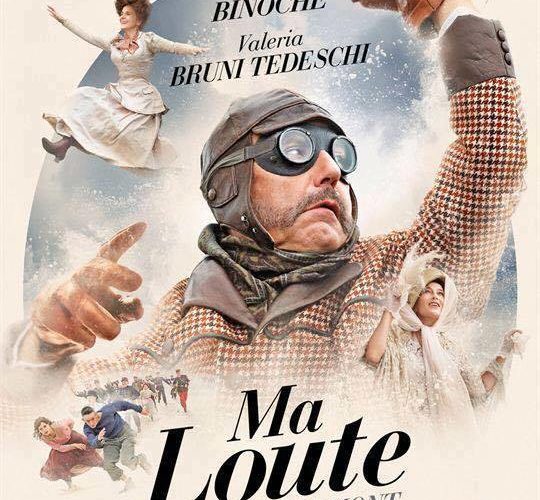

The most important innovation, and also this film’s greatest weakness, is its focus on an upper-class family played by well-known actors. Dumont has long proven his aptitude for working with non-professional performers, and his only collaboration with a major star to date, Juliette Binoche in Camille Claudel 1915, turned out just as fruitfully. Here, he reunites with La Binoche, and also brings in Fabrice Luchini and Valeria Bruni Tedeschi. The results are dreadful. While Bruni Tedeschi is merely unremarkable, Binoche and Luchini are nigh unwatchable. It’s odd to criticize actors for being hammy when the script dictates that their characters be grotesque, but both performances are a caricature of a caricature. Throughout, they are manifestly straining to fit into Dumont’s idiosyncratic comic mold. At a loss, their attempt at compensating through excess becomes extremely irritating, never funny.

Set in 1910, the quirky yet increasingly tedious story involves Luchini’s André van Peteghem, the patriarch of an incestuous clan of aristocrats, vacationing with his family in their eyesore of a villa – the Typhonium, a real edifice in Egyptian Revival style located in Wissant – on the coast of the Pas-De-Calais in Northern France. There have been a number of mysterious disappearances in the region and the two aforementioned policemen are investigating the case. In terms of comedy, this ridiculous twosome, resembling Laurel and Hardy, are the film’s saving grace. Possessing the excellent name Alfred Machin (i.e. Alfred Thingamajigg), the inspector is a gigantic man who resembles an inflated balloon – a likeness that, at one point, is literalized as he inexplicably floats off into the air, a long rope dangling from his foot – and whose whole figure squeaks and creaks with each step. Speaking in a high-pitched voice, he orders his persistently dumbfounded number two around, attempting to feign authority and noisily falling over a lot.

Sadly, the police are merely a sideshow. Dumont very quickly reveals who is behind the disappearances: a family of fishermen who kidnap and then eat rich vacationers. (In one of the film’s most inspired images, the family’s children sit around a bucket filled with blood and body parts, gleefully sucking on severed fingers, ears, and toes.) The van Peteghems have been spared because the cannibal brood’s eldest son, the absurdly named Ma Loute (Brandon Lavielle), falls for André’s niece-cum-daughter-cum-son, Billie (Raph). Billie may be a girl dressing up as a boy, or a boy pretending to be a girl dressing up as a boy. Dumont never fully clarifies this question – the van Peteghems refer to Billie as “he,” but Billie’s face (as well as a naked shot from behind) leaves little doubt that she’s a girl – nor does he clarify why he came up with it at all. Unless it was just to set up the needlessly vicious scene in which Ma Loute beats Billie senseless after he picks her / him up and feels a lump in her / his groin.

The cannibalism theme is also problematic. It’s possible that Dumont borrowed it from Freudian theory, which posits cannibalism as a crucial element in the foundation of civilization. In Freud’s origin myth, sons ate their fathers because they envied their power and status. The repression of this instinct was the first step towards the construction of civilization. To allow for this development, another instinct that also needed to be repressed was incest. Slack Bay therefore seems to offer its own origin myth, since it depicts the aristocracy as a class on the verge of extinction, soon to be swept away by capitalism and the emergence of the bourgeoisie. Apart from not being the most useful of allegories – what is it illustrating, exactly? – the impression that comes across much more forcefully is that the film’s working class characters are a bunch of remorseless savages, eating whoever happens across their path and pummeling the gender-fluid even though they treated them with nothing but kindness. Ha… ha… ha…

Slack Bay premiered at the Cannes Film Festival and will be released by Kino Lorber on April 21. See our festival coverage below.