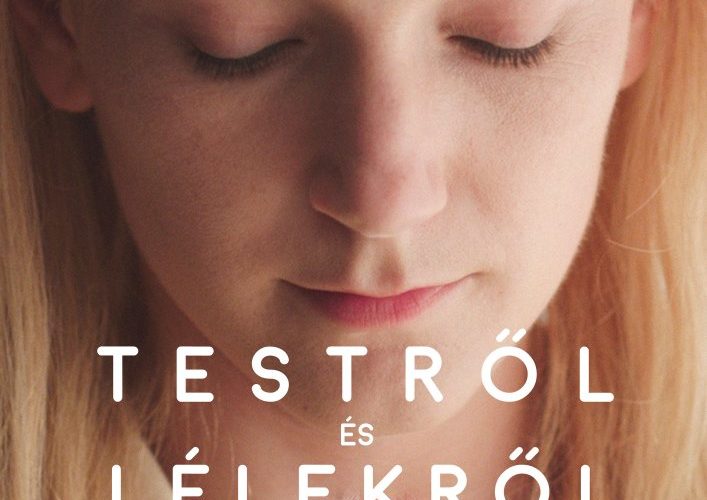

It’s one thing to give your movie a title as sweepingly ambitious as On Body and Soul, but quite another to deliver something equally transcendent. With this competition entry from Hungary, we saw some encouraging signs of artistic experimentation on the first full day of the Berlin Film Festival that’s sorely missing from the opening night presentation, but a home-run is still elusive.

The film opens with shots of two deer roaming, gently grazing against each other in a snow-capped forest. It’s a lovely sight not just for the natural grandeur and inherent serenity of wildlife, but also the camera’s intense focus, describing the texture and temperature of the scene in great detail. This quietly evocative introduction, which would prove to be a recurring theme and much more than mere decoration, leads to a montage of animals in captivity, waiting to be butchered and men, resting blissfully on top of the food chain. The purpose of the striking imagery reveals itself when we learn that the story is set at an industrialized slaughterhouse, where every day livestock is transported gets killed, skinned, prepared for consumption.

As the financial director of the establishment, Endre (Morcsányi Géza) isn’t your typical meat-man. He’s deliberate and soft-spoken, his 60-ish appearance made more vulnerable by a limp left arm. Endre lives by himself and doesn’t seem particularly social. As for women, he admits to have “given up on this chapter of my life.” The newly employed quality inspector Maria (Alexandra Borbély), however, caught his attention the minute she walks into view. Maria, around 30, is quite an odd one with her stiff demeanor and otherworldly aloofness. We know even less of her background except she’s been seeing a therapist since childhood and has pretty obvious reasons to.

The two didn’t hit it off right away, due in part to their shared guardedness and the fact that both seem to have made peace with where they are in life. Not until a company-wide psychological evaluation prompted by a theft did some intimate and rather incredible truth about them get revealed, changing the course of their relationship.

The build-up to this point is very well done. Writer-director Enyedi plays her cards close to her chest, scarcely betraying where the suggestive, visually driven narrative is headed. For the first half of the film, there’s a combination of Terrence Malick, Michel Gondry, and Woody Allen, with its mix of the meditative, fantastical and neurotic. The best individual scene arrives in the form of a long exchange between Endre and the sassy psychiatrist tasked with building his mental profile. Starting with a slight faux pas on Endre’s part, it goes on to map the dynamic shifts between two strangers in a social setting. Humorous with a compelling dramatic arc and a hint of real meanness, it shows how grounds are gained and leverages used in everyday interactions.

Unfortunately, the titillating ambiguity ends soon thereafter as we find out the meaning of those constant cutaways to the deer. To be sure, it’s a brilliant idea with potential for wacko developments, but hopes for the extraordinary keep diminishing as the film gradually falls into the familiar grooves of a quirky dramedy and you realize it’s not going to tell you anything special about body or soul after all.

Featuring a — literally — dreamy central conceit and lots of clever packaging, On Body and Soul seduces, distracts, intrigues, but ultimately doesn’t pack the visceral, spiritual impact that one might expect.

On Body and Soul premiered at Berlin Film Festival and hits Netflix on February 2, 2018.