Note: The trailer for Trance, I think, does a good job of representing the film without revealing significant plot specifics. I have tried to stick to that agenda in this review, though there are specifics mentioned that some may consider borderline. Therefore, chalk this up as a mild-spoiler warning.

If you didn’t go for the twisty delights of Steven Soderbergh‘s recent Side Effects, there’s a distinct probability that you’ll be left similarly displeased with Trance, the fantastically depraved new film from Danny Boyle. Like the Soderbergh picture, Trance twists itself until it can’t see straight, discharging clots of backstory and split-second character distortions that are sure to enrage as many viewers as they satisfy. I fall firmly in the latter category, because the head-spinning narrative spirals are always excitingly complemented by the film’s surrounding elements: the shrewdly committed trio of actors at the story’s center (Vincent Cassel, Rosario Dawson, James McAvoy), as well as Boyle’s increasingly electric display of craft, from Anthony Dod Mantle‘s deceptively shimmery cinematography to the pounding thumps of Rick Smith‘s original score. Add in the kinetic flow of Jon Harris‘s editing, and Trance starts to play like a handful of 2013 releases — Simon Killer, Stoker, Upstream Color, even Spring Breakers — that appear to encourage sensory absorption above all else.

A film that doesn’t care to waste time, Trance throws us into a hurl of action right from the outset. Simon (McAvoy), an employee at an auction-house in London, is describing the standard procedure he must take when there’s an attempted theft on a painting. There was a time, he tells us, when perpetrators needed only some brute force to swipe a Goya from the stage, but those years are long gone. There’s an odd, out-of-place feeling to McAvoy’s opening narration, as if he doesn’t realize an audience is listening — or he does, and he’s simply delaying information for effect. It’s not really clear who he’s talking to, or why Boyle keeps inserting shots of McAvoy as he stares blankly into space, saying nothing. Even the process of his job doesn’t appear terribly intricate — he puts the painting in a sleeve, and then takes it to a vault — but the overarching style of the sequence gives it an importance, implying a layer we haven’t grasped just yet.

When Franck (Cassel) and his goons show up at Simon’s auction-house, a few of our questions are quickly answered. Simon, noticing Franck’s group wielding baseball bats and unleashing gas, stuffs the Goya into a black sleeve, and a team of guards leads him towards a corner exit. Franck catches up with Simon, and puts a violent beating on him, knocking him unconscious. The end result of the confrontation is something like this: we learn that Simon was in on the heist all along, that he hid the painting in a secret location before Franck caught up with him, and that he can’t remember the secret location because Franck’s blow to the head purged Simon of his memory. But it’s too easy, of course, for Franck to buy the amnesia story without a little interrogation, so Boyle provides a lovely scene of nail-ejecting torture. After that yields no results, Franck accepts Simon’s memory loss, and the two are then forced to come up with a plan B.

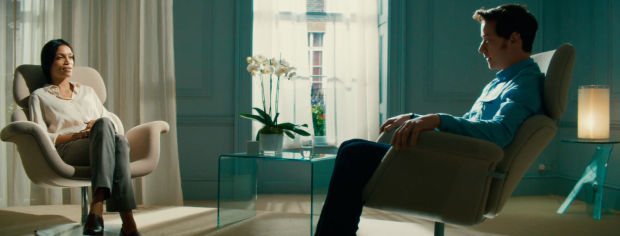

They do some brief research, and end up agreeing on Elizabeth Lamb (a radiantly lit Rosario Dawson), an experienced hypnotherapist, as a possible solution to their problem. Lamb’s office is one of the film’s many sharp, stylish achievements within the realm of contemporary-set production design: the uniform baby-blue walls are perennially dreamy, even crib-like, while the bare-minimum of physical objects (some flowers, a glass of water) does away with distraction and zeroes in on the minds of the therapist and her patient. Simon is told by Franck and company to keep his admissions vague — to tell her, for instance, that he lost his keys, and not a worth-a-fortune Goya — and this gives much of the early interaction between Dawson and McAvoy a tingling comedic edge. Simon’s so clearly attracted to her, though, that the film can’t help but eventually lose itself in delirious psycho-sexual fantasies. But these first sessions are crucial and effective, establishing the wires Simon wears on his chest, and then casually cutting to the guys listening in from the van outside. Boyle picks another grimy detail to linger on: the band-aids covering the spots where Simon once had fingernails.

It’s made clear in these sessions that Simon is an unusually vulnerable and manipulatable subject when it comes to hypnosis, and Elizabeth’s confidence in her ability to decode Simon’s memory stems, at least in part, from her recognition of this very aspect of Simon’s mind. (She’s nearly as adept at infiltrating the rest of the gang, too: one scene has her teaming up with Simon to lull one of the other thugs into envisioning himself being buried alive under a fountain of mud.) She uses this knowledge of Simon to play Franck a bit: after confirming that Simon is somehow involved in a criminal scheme, she demands to meet with Cassel’s threatening headmaster, and shows no hesitation in squirreling her way into the group, requesting a cut of the money for her part in retrieving Simon’s memory. It’s here that the film — with its full-of-itself jargon and its head-first exploration of how we create our memories — invites a comparison to Christopher Nolan‘s Inception. (The slick, savvy suits worn by the ensemble are another Nolan staple.)

But whereas Nolan treats the mind like a puzzle that can be solved with hard, mathematical precision, Boyle treats it like a puzzle where the pieces don’t quite fit together, and where the picture on the box mutates whenever you look at it to check your progress. Boyle, in other words, treats the mind with an appropriately hyperactive charge, as if he wants to move his film so fast that it essentially mimics the speed at which our minds race. The sensuality flows naturally from there: the film’s group-sex dynamics are, in a way, explicit illustrations of the subliminal tension that informed Shallow Grave, Boyle’s 1994 debut film about three friends (two guys, one girl) living under one seriously messed-up roof. Trance‘s loyalty to forming grisly, ferocious violence is reminiscent of Boyle’s earlier work, too, and these connections make sense: the screenwriter here is John Hodge, who collaborated repeatedly with Boyle on several films — Shallow Grave, Trainspotting, A Life Less Ordinary, The Beach — during the director’s edgy early-career phase. (Trance, it should be said, has a second credited screenwriter: Joe Ahearne, who wrote and directed a TV movie of the same name in 2001.)

If you like your Boyle straight, sincere, and rousing — much like his previous two films, the Best Picture-winning Slumdog Millionaire and the James Franco-starring 127 Hours — then you might be best off steering clear of Trance. However, I don’t want to make it sound as if I like the film merely because I reject Boyle’s recent work: I respect his two partnerships with writer Simon Beaufoy, and, though I comfortably prefer Slumdog, I admire 127 Hours on a conceptual level, as an experiment that many people in his position would’ve have attempted. There’s no denying, though, that the guilty-pleasure excesses of Trance are even more welcome after seeing Boyle try his hand (and succeed) at cracking the mainstream. Trance is a film of ridiculously primal relishes: a naked Rosario Dawson playing with a gun (she’s naked in many other scenes, too); a frazzled Vincent Cassel storming his way down a yellow, sky-high garbage chute; an utterly confused James McAvoy picturing his steamy fantasies, using them to construct a narrative he never could’ve guessed. If the film winds itself into oblivion, it’s for a good cause: providing Danny Boyle with a back-to-basics platform, a nasty, cutthroat genre exercise that subverts our desires as vigorously as it discovers them.

Trance opens in limited release on April 5th.