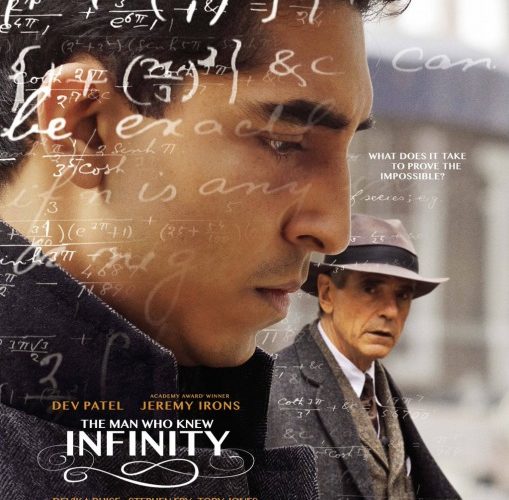

A bit character in Matt Brown‘s affecting biographical drama The Man Who Knew Infinity chants “Din, Din, Din, Gunga Din” a couple times in friendly jest as a response to his employer G.H. Hardy’s (Jeremy Irons) decision to send for an uneducated South Indian man on the merits of a letter presenting the potential for mathematical genius named Srinivasa Ramanujan (Dev Patel). We laugh at the line’s delivery as well as Hardy’s humored look of contempt because we embrace levity. What’s ironic, though, is just how close to Rudyard Kipling’s tragic poem this story of a true intellectual legend proves. The “abuse” isn’t physical and Hardy almost instantly acknowledges Ramanujan to be the better mind, but similarities including its depiction of race relations between Britain and India remain.

This is why I found myself enjoying the film as much as I did. It’s not a strict biography despite focusing so heavily on Ramanujan and his relationship with the man who’d become his mentor and friend. It of course excels on that level effectively considering I’ve left it with a working knowledge of these men’s real-life counterparts, but its true merits lie in its ability to expose a period in time we’ve seen from so many other vantage points with the Brits almost exclusively shown as beacons of heroism. I’m not saying they’re by any means villains here, but they are given an authentically drawn air of adversarial ego when it comes to giving an outsider — especially an Indian — preferential treatment in status and esteem.

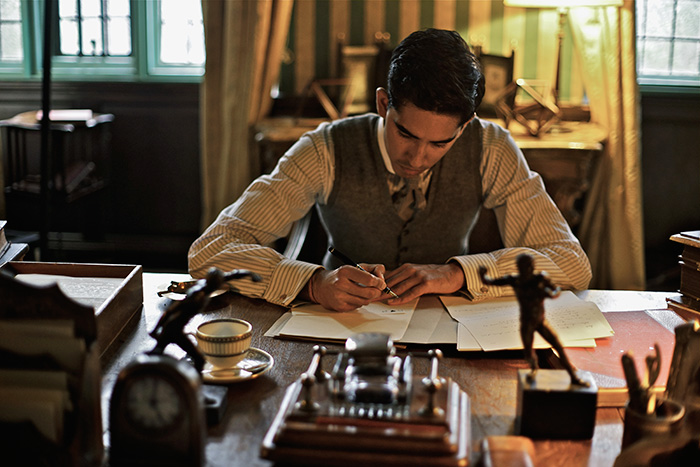

So we aren’t given this glorious journey of a genius plucked from obscurity as much as we are the trials and tribulations of success. Brown’s film is all about the hardships thrust upon Ramanujan; the impossible decisions he must make to ensure the world knows the imaginatively unique formulas he conjured through conversations with his God. This is a Hindu raised in a culture where leaving his home of Madras is forbidden and yet he cuts his hair, scares his mother into believing she’s been abandoned, leaves his wife (Devika Bhise) behind with a promise to send for her, and travels into the great unknown. He isn’t a city resident of Calcutta or Bombay with the pedigree to study at Cambridge. England wasn’t even a dream.

Yet here he is embraced by the kindness of intellectuals who see the work’s merit and therefore the man preparing it (Toby Jones‘ Littlewood and Jeremy Northam‘s Bertrand Russell); berated by the prejudices of those taught to look down on “inferiors” at-large let alone men of color presuming to do what they and their heroes never could (Anthony Calf‘s broadly arch opposition Professor Howard and Kevin McNally‘s Major McMahon); and used, for lack of a better term, by the likes of Irons’ Hardy whose enthusiasm is so contingent on the math that he forgets Ramanujan is a human being craving more than simply tough love and empty praise. It’s okay initially because the young man has Littlewood and Northam to supply compassion. War, however, changes everything.

The declaration of World War I takes The Man Who Knew Infinity further than the math and whether or not Hardy can help Ramanujan prove his theories and announce him to the world as the genius he know him as. Suddenly Littlewood and Northam are gone. Fellow students drafted into the fight become filled with misplaced rage at the foreigner allowed to remain studying while they die. And Howard and McNally’s bigotry refuses to let them see past his skin and station on the social hierarchy of Britain to even fathom that he might bring something of value to the table. Hardy’s so intent on forcing Ramanujan to finish proofs that he’s breaking the boy’s unbridled spirit just as the rest leave him on an island alone.

We see the racial ramifications in England as we witness the religious and familial ones back in India between mother and wife. Irony again enters the fray because while Ramanujan is by far the film’s most pompous character (Patel miraculously performing the role in a likeable way that has us believing he’s as good as he says rather than spouting nonsense), everyone else can’t stop thinking or acting in his/her own self interests. Ramanujan is doing everything for the bigger picture, understanding the responsibility explained by his Indian mentor — holding the power to prove to the British that the brightest Indian minds are equal to theirs. He knows his ideas must be shared and he makes the sacrifices to do so. Does anyone else, though?

You’d be hard-pressed to even say Hardy does, especially at the beginning. His is a complicated character saddled by difficulties of the social and emotional nature. We know straightaway that he’s abrasive, married to the work, and introverted. He converses only when it matters; doesn’t seek to know anyone on a human level — because it’s inconsequential rather than disinterest; and seems content to exist in his bubble of academia without worrying about his surroundings. Hardy sees himself as a facilitator for Ramanujan, a business partner to which he’s happy to put his name underneath in order to be a part of greatness. He’s admirable and crucial to Ramanujan’s legacy, but don’t be surprised to learn he may have harmed the boy as much as helped.

What tale of genius doesn’t come with a healthy portion of tragedy, though? This one is simply more resonate because Ramanujan didn’t have to endure it. To find a voice like Hardy’s to acknowledge him took a lifetime so working to change everyone else’s minds was always an uphill battle. Ramanujan’s story is A Beautiful Mind meets Something the Lord Made and is just as heart-wrenching and important. You may not know his name, but the static epilogue of captioned images explains how Ramanujan should be held in the same esteem as Sir Isaac Newton. The Man Who Knew Infinity circles math, but it’s really about life. Ramanujan was provided an immense opportunity and he literally gave everything he had to ensure it wouldn’t be squandered.

The Man Who Knew Infinity opens in limited release on Friday, April 29th.