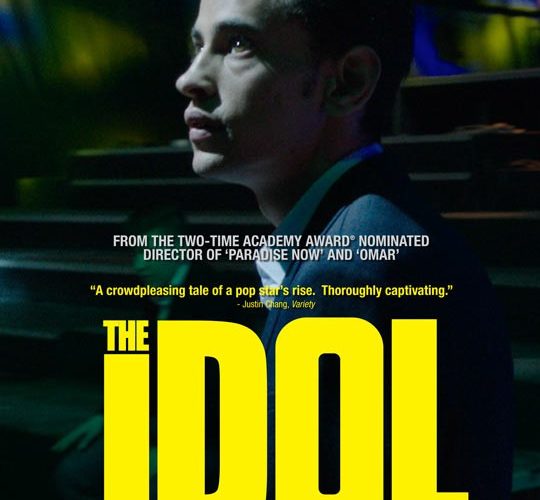

Take your pick in categorizing The Idol: either “based on a true story” or “inspired by true events,” perhaps the binary being alluded to of prose versus poetry. Hany Abu-Assad’s biopic of the Palestinian Arab Idol winner Muhammad Asaf (Tawfeek Barhom) certainly straddles the line between the two to varying levels of success.

Within the promise of both didacticism and feel-good sentiment (a seemingly proven correct recipe for a Best Foreign Film Academy Award nomination), there at least initially seems to be somewhat of a narrative gambit by splitting the film into two halves. Beginning in 2005 and thus placing us medias res in Muhammad’s childhood, we find him close with his tomboy sister Nour, who encourages his prodigy-like singing ability.

Along with two other members, they eventually form an all-child band that frequently performs at weddings (this could certainly be the subject of its own treacly crowd-pleasing festival film). In this stretch, Muhammad doesn’t necessarily feel like the lead (even as the band’s singer) and moreso, the film doesn’t depict rosy childhood nostalgia; almost every small victory is met with a setback (trying to steal the equipment for their band leads to violence, even against children) and in a repeat visit to the hospital, tragedy ultimately strikes Nour.

After this, we see a cut seven years later to Muhammad as a taxi driver making his living in Gaza’s destroyed state (a shot through the moving window of his car showcases the likely real, shot on-location wreckage). Reminded again of his exceptional singing talents by two passengers, he then begins a journey to reach an audition for Arab Idol in Cairo. His attempt to illegally cross the border thus puts the film into political thriller territory — the threat of violence throughout the first half of the film escalating from fists to guns, and personal to political.

Like in Paradise Now, Assad uses bold widescreen compositions, far less for busy frames, but rather to isolate his characters. Just how seemingly uncomfortable the film feels in truly inhabiting the musical and inspirational biopic genres is tipped off by the often desolate images. By the time the film creates a clumsy echo between its opening chase scene of Muhammad and his young friends traversing through tunnels and a later instance of him escaping from border guards, a lack of imagination on Assad’s part is revealed.

Perhaps what was needed was a triptych to challenge its easy narrative victories, perhaps akin to Jia Zhangke’s recent Mountains May Depart. Assad certainly alludes to technology as the defining factor between the two periods, whether Skype or YouTube, and the end in particular is a testament to this: a mix of archival footage showing the response to Muhammad’s national triumph. Yet to present it so earnestly feels like not enough, as if the underlying threat of violence and terror throughout the film was less a reminder of reality than simply a narrative obstacle to be overcome.

The Idol is now in limited release.