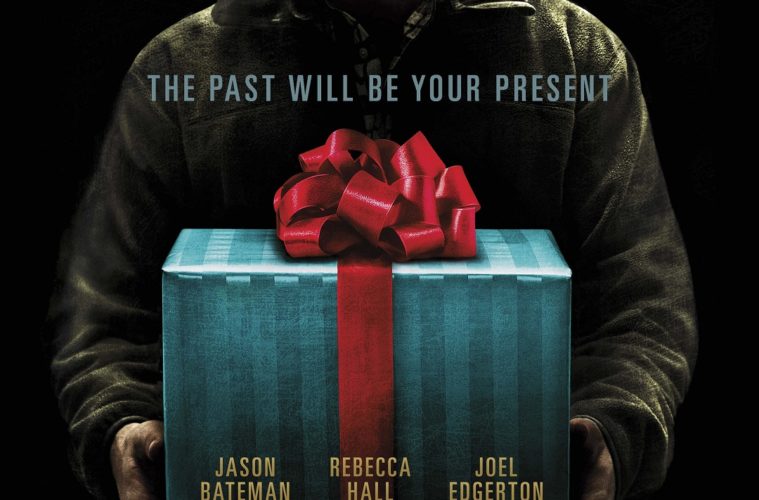

In his thoroughly strategized directorial debut The Gift, actor-writer Joel Edgerton recognizes curiosity as a seed. He plants one hardly five minutes in, based on the relatable subject of weird people you know in high school, and the self-amusement in seeing how they’ve turned out years later. Jason Bateman and Rebecca Hall play Simon and Robyn, a married couple who have moved back to his neck of the woods after a personal tragedy in Chicago. In a furniture store, they meet Edgerton’s Gordo, high school classmate of Simon, who talks sheepishly but with interest in reconnecting. Harnessing the throwaway sentiment of “we should catch up sometime,” Simon kind of blows him off, while muttering to Robyn that Gordo (“The Weirdo”) was a joke decades ago, too.

The Gift finds ample horror opportunity within the sentiment of personal space, as Gordo then squeezes himself into their life in a literal glass house. Gordo does nothing harmful but show that he doesn’t understand unwritten social boundaries, whether it’s leaving a present on their doorstep without asking for their address, or overstaying his welcome when home alone with Robyn. In this construction of an everyday social villain, Edgerton churns out a sense of danger from awkwardness about the other. Nonetheless, after Simon gets tired of Gordo’s “strange” behavior and courtesies, he tells Gordo to leave him and Robyn alone.

And like that, Gordo is gone. This is where Edgerton’s game has to be respected (so I’ll be frugal with details) in which The Gift takes its true form. The trailers promoting it are pretty thorough in showing the third act (while rearranging some details), but the movie’s experience is much different; the pacing is more deliberate, its lack of focus more jarring, and a climax is not in sight. There’s a decent chunk within The Gift that uses the grip from Edgerton’s tense first act to carry viewers to an unanticipated place, in which it’s now not about Gordo, but a mis-communicating marriage, and how we use the progress of time to escape. Of the film’s numerous influences, The Gift intellectually aligns to something like Rian Johnson’s Looper, in which the territory changes midway through, but the significance within character and narrative atmosphere is enhanced.

Keeping his film lively, Edgerton is equally playful and confident. The Gift has little details that elevate the story and tempt on-the-nose reactions, such as a glass house setting, or having a character named Simon immediately associated with “Simon says.” As the tension that Gordo unintentionally (?) inflicts continues in the story, Edgerton is even sharp to a viewer’s nervous laughter. In a shot that keeps the film unhinged, Edgerton gives an extended reaction shot to a dog’s weary gaze, exemplifying the possible horror and/or absurdity of this entire situation.

Bateman and Edgerton provide full performances as the film’s two pieces that transform entirely. There’s never been a juicier film role for Bateman, as he builds upon the smugness he sometimes had as Arrested Development‘s Michael Bluth, while embodying a macho desperation to let bygones be bygones. Meanwhile, Edgerton’s walking-mystery box Gordo volleys from strong discomfort to genuine sympathy, his flaws grounded as human, his moral limits untold. As the significance of these characters mutates, Edgerton (as writer-director) only gets a bit overzealous with their dynamic; there’s a striking scuffle in a parking lot towards the end of the second act that involves the two, and through directorial blocking and dialogue, it very nearly turns their new significances into roleplaying. But as testament to the power within The Gift, this scene touches upon a sociopathic nature within former high school peers, coming this side of Jason Reitman’s Young Adult.

Hall remains the assailable straight line throughout Edgerton’s tale. She does involve us in some finely-orchestrated moments of unease (shout-out to the sound designer and mixer) especially in scenes in which she’s alone in a house that Gordo may or may not be in. But by the end, her character is the movie’s prize. The film’s denouement is equal parts shocking and problematic, as it makes a disturbing moment more about Simon’s duress, even though it happens to her. The same can be said for how Robyn’s anxieties about Gordo are physical-related, while his former classmate Simon does not feel the same threat (a couple notes about Robyn’s already-traumatized mental state is an afterthought). Among this non-gory thriller’s antiquities – Gordo stalks front doors, not Facebook – using a woman strictly for vulnerability is one of its least charming gestures.

In its more sophisticated aspects, The Gift is the triumph of an acting-writing-directing triple threat who knows what an audience wants, but also just how much they need. Edgerton is able to orchestrate tension without solely relying on it, and through the common ground of awkward human interaction creates a horror villain far more traumatizing than the boogeymen found in other Blumhouse projects. His film only gets stronger when it evolves to drama, its tale of born-winners and losers providing the deepest cut.

Giving viewers a horror they’re not expecting, Edgerton understands that viewers will track a mystery to its third act, even when the initial focus is sidelined in the second. Edgerton also knows that whenever someone is too nice to us, or gets too close, too soon, they must obviously be some sort of psychopath.

The Gift opens in wide release on Friday, August 7th.