The latest feature from internationally heralded Chinese filmmaker Zhang Yimou, The Flowers of War, is not a tale of soldiers and strategies, but rather of the women and children caught in the crossfire of war. Based on Geling Yan’s novel The Thirteen Flowers of War, this sweeping historical drama is set amidst the horrific backdrop of the Rape of Nanjing, the six-week period in which the Japanese invaded Nanjing, China, and killed hundreds of thousands of Chinese civilians, then–as the weeks drew on–raped the survivors. Yimou, who has created such visually stunning features as House of Flying Daggers and Ju Dou, does not shy away from the brutal realities of this heinous moment in history. The film’s violence is unrelenting and yet beautiful, punctuated with the bold colors for which Yimou is known. For example, when a war-torn building is blown sky high, amid the gore and dust, hundreds of vibrant boxes and ribbons also take to the air, creating an explosion of incredible violence and color. Details like this—where gore and grace share screentime—can be found throughout the film. This is because The Flowers of War is a tale of lightness amid the dark, bravery in the face of brutality, and the humanity and heroism found even within the cruel crush of war.

The latest feature from internationally heralded Chinese filmmaker Zhang Yimou, The Flowers of War, is not a tale of soldiers and strategies, but rather of the women and children caught in the crossfire of war. Based on Geling Yan’s novel The Thirteen Flowers of War, this sweeping historical drama is set amidst the horrific backdrop of the Rape of Nanjing, the six-week period in which the Japanese invaded Nanjing, China, and killed hundreds of thousands of Chinese civilians, then–as the weeks drew on–raped the survivors. Yimou, who has created such visually stunning features as House of Flying Daggers and Ju Dou, does not shy away from the brutal realities of this heinous moment in history. The film’s violence is unrelenting and yet beautiful, punctuated with the bold colors for which Yimou is known. For example, when a war-torn building is blown sky high, amid the gore and dust, hundreds of vibrant boxes and ribbons also take to the air, creating an explosion of incredible violence and color. Details like this—where gore and grace share screentime—can be found throughout the film. This is because The Flowers of War is a tale of lightness amid the dark, bravery in the face of brutality, and the humanity and heroism found even within the cruel crush of war.

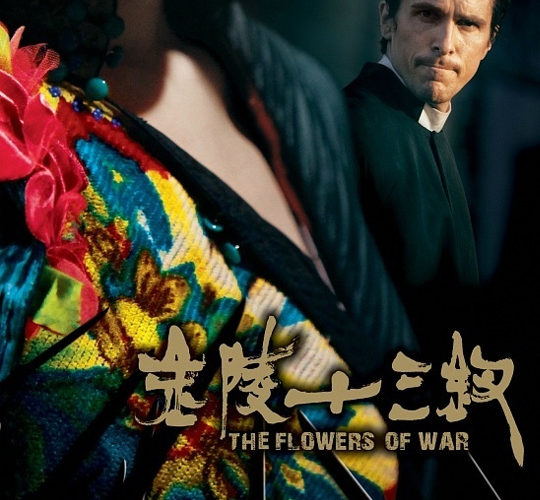

The Flowers of War centers on a young girl named Shu (newcomer Zhang Xinyi), a student at the local convent school. At the start of the film, she and her adolescent classmates are running fearfully through Nanjing, seeking the sanctuary of their church. Carnage surrounds them as bullets whiz by and Japanese soldiers kill any and everyone in their sight. Along the way, Shu and two friends get separated from the group, and cross paths with a lone American, John Miller (Christian Bale), who has come to town to bury the recently deceased priest of the girls’ school. He’s no man of God, but a mortician seeking a paycheck. After getting the girls safely back to the church, he promptly demands payment from their pint-sized caretaker, a young boy named George (Huang Tianyuan). But George insists that they have no money, no parents, nothing. Frustrated, Miller begins to ransack the place, looking for collection money or something he can sell so the trip won’t be a total loss. Meanwhile, a flock of courtesans—headed by the sinfully chic Yu Mo (newcomer Ni Ni with a striking screen presence)–hops the wall surrounding the church, demanding sanctuary. With their snug-fitting dresses, bold red lips and slinky struts, they are unlike anything the girls of the convent—with their regulation bob haircuts and make-up free faces—have ever seen. They hate each other on sight. John, on the other hand, is instantly enchanted by the glamorous and cool Yu Mo, much to the chagrin of Shu, who has developed an intense crush on this bristly, bearded outsider.

The Flowers of War centers on a young girl named Shu (newcomer Zhang Xinyi), a student at the local convent school. At the start of the film, she and her adolescent classmates are running fearfully through Nanjing, seeking the sanctuary of their church. Carnage surrounds them as bullets whiz by and Japanese soldiers kill any and everyone in their sight. Along the way, Shu and two friends get separated from the group, and cross paths with a lone American, John Miller (Christian Bale), who has come to town to bury the recently deceased priest of the girls’ school. He’s no man of God, but a mortician seeking a paycheck. After getting the girls safely back to the church, he promptly demands payment from their pint-sized caretaker, a young boy named George (Huang Tianyuan). But George insists that they have no money, no parents, nothing. Frustrated, Miller begins to ransack the place, looking for collection money or something he can sell so the trip won’t be a total loss. Meanwhile, a flock of courtesans—headed by the sinfully chic Yu Mo (newcomer Ni Ni with a striking screen presence)–hops the wall surrounding the church, demanding sanctuary. With their snug-fitting dresses, bold red lips and slinky struts, they are unlike anything the girls of the convent—with their regulation bob haircuts and make-up free faces—have ever seen. They hate each other on sight. John, on the other hand, is instantly enchanted by the glamorous and cool Yu Mo, much to the chagrin of Shu, who has developed an intense crush on this bristly, bearded outsider.

However, these petty grudges are forced aside when the horror of war invades the church. After the Japanese breach the protective walls of the church, the girls try to make it to the secret basement where the courtesans hide, but failing that are terrorized by malicious Japanese soldiers who ghoulishly attempt rape within the walls of the church. It’s at this moment that John goes from a selfish drunkard to a hero. Dressed in the dead priest’s robes, John confronts the Japanese soldiers in a scene that is both breathtaking and heartbreaking. From here on out, he is not a selfish American, but the father-figure to a dozen girls and a hero to the women of the red light district. Realizing the Japanese will return, he begins a plan to get them all out of Nanjing.

However, these petty grudges are forced aside when the horror of war invades the church. After the Japanese breach the protective walls of the church, the girls try to make it to the secret basement where the courtesans hide, but failing that are terrorized by malicious Japanese soldiers who ghoulishly attempt rape within the walls of the church. It’s at this moment that John goes from a selfish drunkard to a hero. Dressed in the dead priest’s robes, John confronts the Japanese soldiers in a scene that is both breathtaking and heartbreaking. From here on out, he is not a selfish American, but the father-figure to a dozen girls and a hero to the women of the red light district. Realizing the Japanese will return, he begins a plan to get them all out of Nanjing.

With it’s massive scope and extraordinary cinematography, it’s little wonder that this feature was chosen as China’s Oscar submission for Best Foreign-Language Film. There’s plenty to praise in Yimou’s Flowers of War, which with a budget of upwards $100 million is China’s most expensive film production to date. The film is filled with breathtaking visuals that are in turn gorgeous and gruesome. Disturbing images of war are counterbalanced with various loving images of the sweet grace of the girls and undeniable sensuality of the women of Nanjing, who are often caught in blazes of color from the church’s vivid stained glass windows. Flowers is likewise punctuated with powerful performances. Bale is stirring as a mortician masquerading as a priest, and his scenes with Ni are filled with a palpable heat. Likewise, young Xinyi, who was plucked from obscurity for the production, is solid in the subtlety of her performance. It’s an incredible epic that’s poignant and powerful, even though Yimou struggles with the multi-language aspect of the film. Characters restate exposition to each other in different languages or verbalize what is understood without words, adding to an overlong runningtime of 141 minutes. Still, it’s a fascinating story told by a master filmmaker. Bold, brutal, and beautiful, The Flowers of War is a must-see.

The Flowers of War opens in NY on December 21, expanding to Los Angeles and San Francisco on December 23.

Watch the trailer here.