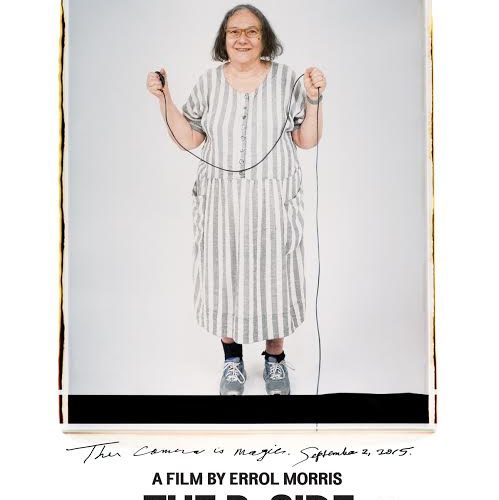

The B-Side: Elsa Dorfman’s Portrait Photography winds up feeling in many ways like the much-talked about concept of its protagonist. That is to say, the stuff left behind. Like Elsa Dorfman’s portraits that were not chosen by the families she took them for, a lot of the film’s own footage feels like it has its own charm and happy glint, but is nevertheless a bit dull and lifeless. It is constructed with care, and there is clearly love in its cutting and musical choices and why life has been given to it. Unfortunately, it feels like a project whose outward reach has not been figured out, feeling like a collection of moments perhaps better reviewed by the capturer in a private space, than shared with the world.

This is a shame, because Dorfman is filled with interesting stories and maintains a collection of historical photography. She has pictures of Bob Dylan and, of most pertinent interest to the filmmakers, Allen Ginsberg, who she shared a close bond with. Yet these stories are congealed together, one after the other, in the same space, with often the same framing. Then quality scans of the images she’s referring to come up, as does melancholic and reminiscent music. This works to establish the tone and content of the piece, but when it is used over and over again, it begins to feel like a History Channel special instead of a personal and intimate portrait of something or someone.

There are ideas of interest that are touched upon, such as the aging of the photographic art form and film itself, and that is reflected in the idea that an aging artist works within an aging medium. This concept carries a poignancy of its own, but it is not enough to overcome a technical presentation that more affirms a stereotype of banality than presents what I believe to be reality — that art and artists can always be fascinating and make powerful work, regardless of age. This all stems largely from a feeling of sluggish stillness that permeates most of the piece. For most of its runtime, the audience is in the same room with Elsa, as she stands in mostly the same place, and talks. The weight of history and energy that can be felt when actually standing by someone recalling their past is lost with this technique of capturing, which creates an unintentionally reflexive comment on the untruthfulness of cinema — something, granted, Elsa does go into.

Yet this fascinating paradox does not feel like an intentional decision from director Errol Morris, who seems to shoot with a true earnestness. This makes for some beautiful frames and straightforward sincerity, but it lacks a momentum or emotional core that allows its subject to become a character we want to follow. It feels like the sort of antithesis to the deeply character-driven lengths of last year’s Peter and the Farm, which had an unflinching and brutally honest eye towards its central figure that made for fascinating study. That’s not to say one should be allowed to compare ‘characters’ in a documentary — as they are, for all intents and purposes, real people — yet it is still a filmmaker’s primary duty to pull forth from the material captured something worth viewing.

In this way, The B-Side feels like it could use some serious restructuring and cutting — a bit of a harsh reality when the film only runs an hour and sixteen minutes. Near its final third, it feels like more interesting ideas and pointed focus start to arise. This is a breath of fresh air, probably because it involves Elsa moving to a new space, and it expands the canvas of the piece in a way that just sort of makes you wish it started that way. There is so much meandering and tidbit stories early on that feel like they’d be better suited for an NPR piece than a documentary. This is accentuated and proven by Errol’s camera, which feels like it doesn’t really know what to do than just cut back between about three angles while Elsa talks. Her words are often moving, but the film around her just isn’t.

When all is wrapped up, The B-Side: Elsa Dorfman’s Portrait Photography shows glimmers of beauty and poignancy that are drowned in an overwhelmingly sense of stagnancy. This leaves the viewer trapped in a space of confusion, where the subject matter is of interest, but just perhaps placed in the wrong medium. If one wishes to get a glimpse into Elsa Dorfman’s life and work, this is not a poor place to do it. But as a documentary standing on its own two feet, it stumbles.

The B-Side: Elsa Dorfman’s Portrait Photography is now in limited release.